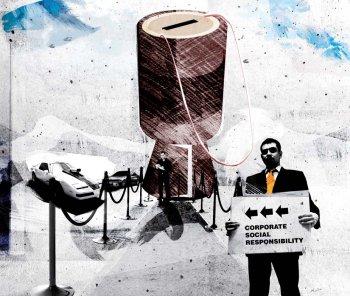

Corporate Donations -- CSR: The new PR

By Karryn Miller

Corporate social responsibility is now a business prerequisite, but how has it affected the way charities do business?

With CSR becoming such a buzzword, are businesses lining up to donate?

With CSR becoming such a buzzword, are businesses lining up to donate?

Hailing from the US educational elite—Yale, Harvard, Princeton, and Brown—it is not surprising that the guests at a recent ‘Room to Read’ (RtoR) event were interested in learning about a charity that gives the lasting gift of an education. It does, however, come as a surprise to hear where the event took place.

Gucci’s Ginza cafe played host for RtoR—giving the NPO 20 percent of its sales that night, donating designer Italian bags, and offering a preview of its upcoming spring collection. So what does a fashion powerhouse like Gucci have to do with impoverished children? More than you may think.

“Gucci appeals to strong, independent, self-assured women,” say David Ray and Meg Nakajima, co-leaders of RtoR’s Tokyo chapter. “Room to Read has 6,500 girls on scholarships in nine different countries. With the life-long gift of education, these girls will grow up to be strong, self-reliant thinkers. According to research, a woman’s income increases 10 percent for every year she goes to school.”

Although recipients of an RtoR girls scholarship may not necessarily rush out to a Gucci store upon graduation, there is reasoning in Gucci’s corporate responsibility endeavors. Like other companies, Gucci is looking to align itself with charity activities that link with the business—as well as doing good.

CSR equals PR

“The fact that CSR is a PR opportunity has increased the number of companies who are willing to partner with Room to Read,” explain Ray and Nakajima. “As a global brand supporting education in Asia and Africa, we are focusing on building relationships with companies that are doing business in the countries where we build schools and fund scholarships for girls. It makes strategic sense that Room to Read tries to develop partnerships with companies like Honda and Panasonic since they have large operations in Vietnam. Developing an educated workforce is in their best interest.”

RtoR’s impact can be immediately seen—donations translate directly into schools, libraries and other educational pursuits. But for charities where the funds cannot be converted into concrete objects, how difficult is it to get the support they need?

“Amnesty International (AI) spends its income on research, campaigning, lobbying, and education (on human rights),” explains Chris Pitts, Amnesty International’s Tokyo English Network (AITEN) coordinator. “My experience is that it is much easier to get a corporate donation for say, building an orphanage in Cambodia or providing clean water to a village in Burkina Fasso, than it is to get a corporate donation to AI.” He adds, “The bigger and more international the company, the more difficult it is, because AI might be criticizing the human rights situation in a country they may be doing business with in the future.”

However, the cautionary approach to support has to work both ways: AI is required to carefully screen potential donor companies. “It is highly unlikely that we’d agree to accept a donation from any company that had a reason to want to influence us,” says Pitts.

Donation strategy

RtoR believes the way companies donate money in Japan has clearly become more strategic but not necessarily more bureaucratic. “By focusing on key sectors such as the environment, health and education, they are better able to evaluate opportunities that make sense for their corporate brands,” explain RtoR’s co-leaders.

However, Jane Best, president and CEO of Refugees International Japan (RIJ), differs in opinion about the red tape. “Companies expect organizations to be able to meet their business needs,” Best comments. But she does not necessarily believe this to be a wholly negative change. “Before CSR was structured, some donations were given through personal contacts—a good and a bad thing. I believe a more structured approach to supporting charities is generally an improvement.”

Like RtoR, RIJ agrees that “companies should be supporting charities which are good for their business and in the interest of their stakeholders. If it is more rigid for charities, I think this is good because charities should be more structured too. That said, CSR is still a new concept in Japan and many companies are struggling to find a model that best fits their business.”

When it comes to CSR, what stakeholders think is also of prime importance to corporations. According to international accounting and consulting firm KPMG International’s global analysis of corporate reports, 40 percent of companies surveyed globally had their sustainability information— in their corporate reports—assessed by a third-party to make the report more credible to stakeholders and to ensure the quality of information reported was at a higher standard. This jumped by 10 percent from the last survey in 2005. Companies said they sought third-party assessments on their sustainability information for two primary reasons: to improve the quality of the information, and to reinforce its credibility among key stakeholders.

The era of transparency

The transparency of NPO/NGOs seeking funds is just as important as showing stakeholders that donations made by the company are credible. RtoR promotes having an open accounting book for the public to see. “We believe in checks and balances and demonstrating that we keep our overhead very low—currently 13.5 percent of revenue. We conduct internal and external audits and share this information with individual and corporate donors,” say the representatives.

Best believes donation corruption is not a big issue in Japan, but mirrors RtoR’s principles on being open. “It can only be a good thing as charities must be transparent—this encourages good practices.” She adds that “companies are now asking for information on how the money was distributed—what they gained—how it is of interest to stakeholders etc. RIJ does follow up with supporters and this is very well received.”

How companies and individuals are acknowledged for their donations—as well as how they are made—has undergone some changes. “At large fundraising events, the auctioneer used to start with a mock auction by teaching Japanese people how to raise their paddles and make bids. This is now ancient history. The Japanese are now skilled bidders and increasingly the largest donors in the room,” RtoR told us.

Mutual benefits

With an increasing number of companies seeing the potential for charitable donations, NPOs are having to think of ways to improve their chances of becoming the chosen ones. For example, AI Japan has begun investigating ways to develop “mutually beneficial partnerships with the business community,” says Pitts. One way is by encouraging firms to buy AI goods to give as seasonal gifts. “This offers the possibility, if the company is suitable and the order is big enough, of putting the name and logo of both the company and AI on the product, for example, a cotton shopping bag.”

Another way is by inviting companies to support the work of AI by subscribing to be a part of the ‘Board of Patrons.’ Consisting of a limited number of carefully selected companies, the patrons benefit by “being seen to be supporting AI’s vital work defending and promoting human rights around the world.” For this, “AI would publicly acknowledge their support.”

As the financial crisis trickles down to all facets of society, NPOs are understandably concerned about their funding future. As the RtoR co-leaders say; “The biggest question going forward is how the economy will effect donations. With the Nikkei at a 26-year low, we have to work twice as hard for half as much.”