The Decline of Luxury Brands in Japan?

Notorious for its appetite for designer goods, Japan has always been at the forefront of market importance in the luxury brands sector, even being dubbed “the world’s only mass luxury market.” Yet there are signs that sales are declining. As the market matures, what’s in store for the luxury sector?

By Dominic Carter

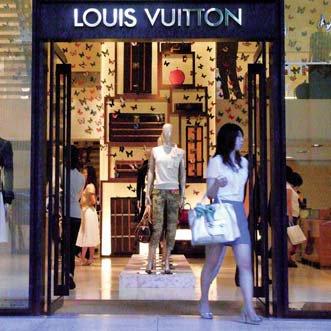

In Tokyo, an often repeated claim is that nine out of ten young women own an item from Louis Vuitton. Whilst the statistic itself has a strong whiff of urban legend to it, the proportion of the urban population in Japan that owns a famous and expensive luxury brand item is significant; much higher than in similarly developed cities such as New York, Sydney or even Paris.

To Western eyes, the seemingly limitless affinity for imported luxury brands in Japan seems to threaten the necessary attribution of ‘exclusivity’ that luxury entails. As a large segment of the population comes to own a brand previously considered to be unattainable, when does this cease to be a luxury and become a compulsory form of social expression? According to David Rudlin, the Tokyo-based Director of International Markets at De Beers, Japan is a fundamentally different market to the West, describing it as “the world’s only mass luxury market.”

The world’s only mass luxury market

Davide Sesia, President of Prada Japan and a long-time observer of Japanese culture, believes Japanese women, to a much greater degree than Europeans, have a “psychological need to own something considered to be beautiful.” He says it is a contrast to young people in Italy, who tend to believe that “they are violating a moral code” if they buy luxury goods. The idea that it is better to be beautiful on the inside is something Sesia claims he has never heard expressed in Japan.

In Western societies we tend to question the morals of those that devote too much attention to luxury. However, Martin Webb, a Tokyo-based public relations practitioner with clients in the luxury sector sees a broader social context: “The affinity for luxury can be assumed to be, at least to a large extent, a result of Japan’s culturally and socially homogenous society, the relatively large middle class, the very high population density, which leads to people spending more time out of the home than in other cultures, and also to a very impersonal society where looks count for a great deal. In Western cultures vanity is sneered at, but there’s no place for the disheveled aristocrat archetype in Japan—people are supposed to dress in a way that corresponds to their social position.”

Why is there a decline?

Yet the reality is that the pressure on the market has been building for years. Japanese consumers do not feel especially prosperous, with their salaries and bonuses having been kept down for years by cautious employers, an increasing trend towards a non-permanent workforce, and more recently, a seemingly endless wave of worrying economic news. Added to this, the shrinking workforce and aging population means that the pool of buyers in their 20s and 30s who have traditionally splashed out on luxury icons is shrinking.

Rudlin of De Beers observes that “people in the middle have traded down.” Whereas in the past, office ladies would think nothing of paying through the nose for a blouse from a top designer, they are now just as likely to purchase this type of functional item from a chain-store like Zara—a trend that augurs well for the imminent entry of Swedish super- retailer H&M into the Japanese market.

Decrying the middle ground

It does not bode so well for brands occupying the middle ground in the luxury sector. In recent years brands like Coach, Tod’s and Hogan, who had pitched themselves as affordable luxury, flourished by featuring a much lower price point for their leather goods than their luxury competitors. Yet it appears that brands serving this portion of the market face the toughest test as their customers are the most likely to trade down to cheaper alternatives, with no similar downward shift from above. Recent research carried out at Carter Associates suggests that brands like Bottega Veneta and Marc Jacobs, brands with a clear, modern and “happening” positioning, have bright spots in the market, whilst brands like Coach and Tiffany that have enjoyed success in the mid-market, face a more challenging environment.

Japanese consumers are becoming less likely to tolerate increases in prices, whereas before, high prices had enhanced desirability. Even though many young women will still save up for the “must have” brand, they are trying to make their money go further—a trend underlined by increased sales for less expensive items such as wallets and clutches. Prada’s Sesia offers an additional perspective, suggesting that from around the year 2000, luxury goods have come to occupy a different position in the consumer mindset: “The increased attitude of Japanese ladies in their 20s and 30s understanding themselves much better than in the past is the key phenomenon right now.” He believes that ready-to-wear has been the most affected category of luxury goods, as Japanese women have pursued more self-directed brand choices.

Maturing market

In the past, luxury brands were purchased as badges of membership to the new urban class, clearly distancing the owner from their humble, ultimately rural roots. The market in Japan has clearly moved on from there, in contrast with the explosive discovery of brand goods in China which is at an earlier stage in its urbanization process. In this respect, the market in Japan is beginning to resemble the norms of mature brand behavior seen in the Western world.

"The market in Japan is beginning to resemble the norms of mature brand behavior"

So what does the future hold for the luxury business in Japan? According to fashion PR executive Webb, “It’s safe to say that we can expect a sustained slowdown in demand for luxury in 2008 and 2009, but we shouldn’t forget that it’s still a healthy, growing industry. Despite the doldrums, analysts are still predicting growth of about 6% for the next couple of years, and you’ve got to remember that the sector has never seen an annual sales decline.”

Rudlin of De Beers believes that despite a tendency for the Japanese to react disproportionately to economic uncertainty there are still opportunities for luxury brands, suggesting that “if you can find the right positioning, the right messages, this is still a very wealthy country.” He says that there has long been a strong cyclical nature in Japan where periods of lavish spending are followed by periods of regret and frugality.

Sesia of Prada believes that the market will recover, but not as quickly as in the past. He holds that the more sophisticated consumer trend is here to stay: “In order to compete you have to make your marketing decisions and strategy much more sophisticated.” He adds that prices of individual items and lines will fluctuate (as they always have) but, “the average price will be one of the most important topics in the luxury industry in coming years.”

In years to come Western luxury brands with businesses in Japan will need to cater to a more complicated range of aspirations, and will compete with a wider range of competitors for any given luxury spend. For companies selling into Japan this increased market sophistication should create as many opportunities as it does threats, and the market will remain a highly rewarding one for brands that can meet a more nuanced consumer at her own level. JI

Dominic Carter is President of Carter Associates, a leading market research company.

Top Ten Favorite Brands For Japanese Women

|

1. Louis Vuitton 2. Coach 3. Hermes 4. Gucci 5. Burberry |

6. Cartier 7. Dior 8. Chanel 9. Prada 10. Tiffany |

A survey of 400 females aged 18 to 49 in the Kanto, Chubu and Kansai region. Conducted by Carter Associates KK.

Comments

Anonymous (not verified)

September 15, 2008 - 17:44

Permalink

The Urban Legend

"In Tokyo, an often repeated claim is that nine out of ten young women own an item from Louis Vuitton."

Not only has this been disproved, it was disproved months ago and very publicly.

<karo (not verified)

January 19, 2009 - 16:09

Permalink

info on Japan

War heute ein größerer Bericht auf CNN über die Konsumkrise in Japan, vor allem bei Luxusgütern;)

Anonymous (not verified)

February 6, 2011 - 21:09

Permalink

頑張って

頑張って日本!