The Recycling Champs

Back to Contents of Issue: August 2002

|

|

|

|

by Yaeko Mitsumori |

|

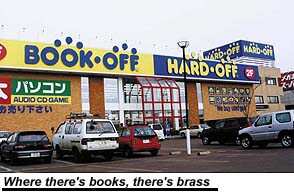

THESE COMPANIES TURN TRASH into profits. With each piece of legislation further restricting the way we dispose of the detritus of everyday life, their profit margins swell. And as the Japanese archipelago slumps under the weight of a relentless economic downturn, the recycling champs keep building, growing and expanding. They are frugal, no-nonsense -- they are not interested in image, but their bottom lines are enough to make even the most jaded investor look twice. THESE COMPANIES TURN TRASH into profits. With each piece of legislation further restricting the way we dispose of the detritus of everyday life, their profit margins swell. And as the Japanese archipelago slumps under the weight of a relentless economic downturn, the recycling champs keep building, growing and expanding. They are frugal, no-nonsense -- they are not interested in image, but their bottom lines are enough to make even the most jaded investor look twice.The recycling champs are in the right place at the right time. Japan is growing evermore conscious about the environmental problems it faces, businesses are being pushed to act responsibly and the government is obliging by tightening restrictions on waste. More laws are in the pipeline and that's just what the recycling champs want to see because many of them have been at this business for several years and are ahead of the pack in terms of technology and logistics. Electricals Champ Take Hard Off, a Niigata-based venture that sells secondhand goods through its 295 outlets nationwide (See also Success in Small Packages, April 2002). In November 2000 it successfully conducted an IPO on the OTC market, becoming the nation's first publicly traded comprehensive recycling business. Hard Off opened its first outlet in 1994. Its annual sales for fiscal 2001 were JPY5.5 billion and its latest profits weighed in at JPY1.1 billion. That works out to a 20 percent current profit margin, which is one of the best among Japanese retailers. Yoshimasa Yamamoto, president of Hard Off, designed the outlets to be as bright as convenience stores. He wanted to counter the image of conventional recycling stores being dark and uninviting. He built a database that lists up purchasing prices for 90,000 second-hand consumer electronics and PCs, and he also provides a warranty of up to one year for second-hand goods sold at his outlets. Yamamoto also squeezed expenses as tightly as possible. At a typical Hard Off outlet, which has a floor area of 150 tsubo, or 495 square meters, there are only three full-time employees. All of the Hard Off outlets are open 365 days a year. Since full-time employees are usually busy purchasing secondhand goods that end-users bring into the outlet and settling payments at the cashier, they do not attend to the shoppers much. It's more of a self-serve atmosphere.  Yamamoto says Hard Off is finding support in odd corners. Home appliance stores welcome his outlets, he says, because "since Japanese houses are very small, consumers have to dispose of used home appliances when they want to purchase new ones. The more they bring in their used products to Hard Off, the more they can buy new products."

Yamamoto says Hard Off is finding support in odd corners. Home appliance stores welcome his outlets, he says, because "since Japanese houses are very small, consumers have to dispose of used home appliances when they want to purchase new ones. The more they bring in their used products to Hard Off, the more they can buy new products."Hard Off is also providing an option for home appliance store owners who have fallen on hard times. Yamamoto says most of the Hard Off franchisees are former home appliance stores. Over the past decade, several big chain stores like Sakuraya and Bic Camera have been opening new stores here and there. That's hurt the business of small home appliance stores. Yamamoto himself was the owner of a small home appliance store in Niigata that was on the verge of bankruptcy before he launched his secondhand business. Yamamoto has big plans: He is planning to increase the number of Hard Off outlets to 500 by 2005 and expects total sales to reach JPY9.2 billion and turn a profit of JPY2 billion. He believes that the recycling market for consumer electronics and PCs will increase from the current JPY10 billion to JPY1 trillion by 2010. "We would like to have at least a 10 percent market share and be the leader of this industry," he says.

Food champ

Food champIn Tokyo, Environmental Science Institute Ltd., a garbage recycling venture, successfully launched its business in 2000. Mitsuji Kyozuka, president of ESI, says he decided to launch a recycling business because of the food recycling promotion law, which came into effect in May 2001. It requires all major garbage producers that produce more than 100 tons of garbage a year to cut their waste output by 20 percent by 2006. Kyozuka's ESI collects garbage from these large garbage producers and turns it into compost or feed for cattle. It then sells the vegetables grown by the farmers using the compost and the feed to the original garbage producers. Some big supermarket chains such as Daiei, Peacock and Jusco have begun using ESI's garbage recycling system. One Daiei factory, for instance, produces 10 tons of garbage every day. ESI collects the garbage, produces compost from the garbage, sells the compost to farmers who use it to grow vegetables. Daiei sells the vegetables at its outlets. "Using our system, the supermarket can reduce the garbage, farmers can get quality compost, end-users can buy safe vegetables and fruits and we, ESI, can make money," Kyozuka says. "Every partner of our business will become happy." Currently ESI's main business consists of selling garbage-processing machines that produce quality compost within a couple of hours. ESI has sold these machines to 30 offices and factories representing a dozen companies. For this fiscal year the firm forecasts sales of JPY10 billion and JPY3 billion in profits. Kyozuka is planning to expand ESI's consultation business to help farmers, companies in the food industry and other big firms that produce a lot of garbage. "There are 500 compost machine manufacturers in Japan," he says. "However ESI is the only company that can provide total solution services for these industries." He wants ESI's consultant business to eventually account for half of ESI's sales. Kyozuka, like Hard Off's Yamamoto, is bullish on the prospects for the recycling business. He wants to be collecting garbage from 1,000 factories or offices representing 300 companies by next March. He is also building a network that he says will encompass 3,000 cattle farmers and 15,000 growers of vegetables, fruit and rice. If Kyozuka's big dreams come true, then ESI would be processing about 10 percent of the total garbage disposed by businesses in Japan. "Next, we will deal with garbage from households and will start collecting garbage from 'the second best' garbage producing companies," he says. "If we are successful in Japan, then we will export our business model to other countries." To realize his dreams of expansion, Kyozuka makes use of quasi-governmental facilities. As part of the governmental garbage recycling promotion law, 3,000 compost centers have been built around the country using government subsidies. Kyozuka is planning to select 300 compost centers among the 3,000 and turn them into what he called IRMS (Integrated Recycle Management System) centers. These will be the core facilities for ESI's total system. ESI's recycling model has been approved by some governmental organizations. The Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries and the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare started using ESI's recycling system based on IRMS this spring. ESI is preparing to IPO next year on the OTC. Kyozuka is busy promoting preparation for the IPO with underwriter Daiwa Securities Group and applying for a patent for his business model. Device champ Asaka Riken, a recycling business in Fukushima prefecture, was planning to do its IPO this year, however bad business conditions have forced it to postpone the listing until 2004. Asaka has been around since 1969 and has expanded its business recovering precious metals such as gold and copper from electronic devices and selling etching fluid for semiconductors. The firm rode the IT boom, rapidly expanding sales and profits, but then the worldwide chip recession hit and Asaka Riken was left dazed. The chip recession and a bearish metal market have left Asaka with close to no profit for the fiscal year that ended this March. But don't write this company off just yet. Yamada is leading a shift in focus at the company to what he calls the "function-recycling business." For instance, during the process of making quartz, some devices with impurities are naturally produced. By fully using technologies that Asaka has accumulated through its long recycling experience, the company can strip off the impurities and replace these crystals back into normal devices. Then the quartz maker can use the recycled device for production and can improve its yield. Asaka has a total monopoly of this market. The firm also provides similar services for other devices such as liquid crystal displays. Using the same technology, Asaka is also exploring a new market for cleaning devices with chemicals. The device market had been heavily hit by the worldwide economic slowdown. But Takashi Shimura, executive general manager of Asaka, says the device market has already hit bottom and has been recovering for the past couple of months. "We found good signs in the market," he said. As a next step, Asaka is now planning to explore the overseas market. To avoid high costs, most of its device production has been shifting to China and other Asian countries. "If we bring back the devices and materials to Japan for the recovering process, it is inefficient. We are now considering exploring the overseas market. We are considering going to Taiwan first and then to China. We may build our factories in these countries or conclude a business alliance with local companies," Shimura says. Gas champ In April, Tokyo-based venture Alcat Corp. started selling a machine that purifies VOC (volatile organic compounds) gas. VOC gases such as gasoline and kerosene have been regulated in many countries. What makes Alcat unique is that it launched its ecology business using a patent transferred from the Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology technology licensing office, or TLO. It was the very first technology transfer for the TLO, which was set up last December. Based on the patent, Alcat has developed its first product -- a machine that dissolves VOC into carbon dioxide and water using an alumina catalyst. Thanks to the patented technology, the machine processes VOCs without leaving a bad smell and with high efficiency, using the recyclable alumina catalyst. The company is targeting ink makers, printers, plastic makers and recycling businesses.  Toshiyuki Koya, president of Alcat, says he wants to keep his firm small and profitable. Alcat is outsourcing all its business except the patent management and R&D. Manufacturing is being conducted by Tau Giken and the catalyst device -- the key part of the machine -- is being produced by Alumi Hyomen Gijutsu Kenkyusho. Sales and marketing are conducted by Yasuda Sangyo, a trading firm.

Toshiyuki Koya, president of Alcat, says he wants to keep his firm small and profitable. Alcat is outsourcing all its business except the patent management and R&D. Manufacturing is being conducted by Tau Giken and the catalyst device -- the key part of the machine -- is being produced by Alumi Hyomen Gijutsu Kenkyusho. Sales and marketing are conducted by Yasuda Sangyo, a trading firm.Koya said that he would like to deal with big firms like Nippon Mitsubishi Oil or Japan Energy in the future. "However these big names do not do business with a tiny business like Alcat, a one-man firm," he says. Due to its outsourcing strategies, Alcat is planning to turn a profit in its second year and eliminate all accumulated debt in its third year. Koya said he is targeting sales of JPY1 billion in five years and plans to IPO within five or six years. One big hurdle for technology ventures like Alcat is that they need a heavy initial investment. "We luckily raised the necessary funds from other companies and won subsidies from the government," Koya says. "But I really feel the government has to provide financial support for venture businesses to take off." Koya and the others may be examples of businessmen doing well for themselves by doing good for others. Kyozuka says he started ESI because he wanted to make the earth a little bit cleaner for the next generation. But whatever their motivation, it is clear these recyclers are some of the first ones into potentially very lucrative markets. The Environment Ministry estimates that the environment market, including recycling and reuse, will expand from 1997's JPY24 trillion to JPY39.8 trillion in 2010. "A decade ago when I launched my business, nobody believed my business plan would be successful," says Hard Off's Yamamoto. "Not so many people understood the words 'ecology' or 'eco-conscious.' I feel the times have changed." They have indeed -- and the recycling champs are in a win-win position.@ |

|

Note: The function "email this page" is currently not supported for this page.