The Cartographer’s Trail

By Benjamin Brown

Although rural Japan has long been in decline, Hiroshima’s Onomichi is a hidden pearl in a rusting landscape.

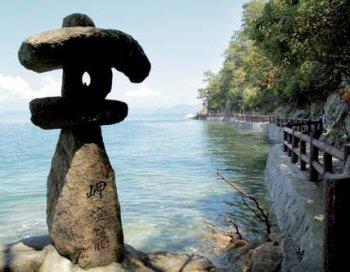

The cartographer’s Onomichi lies at the terminus (or origin, depending on one’s perspective) of a spotty chain of tiny islands forming a bridge between mainland Honshu and Shikoku to the south. Peer over the molluskan ridges of Onomichi’s northern border and you’ll gaze on a long town, cradled against the narrow channel like a Hiroshima oyster in the gentle palm of the Seto.  Many women visit Jizo-hana to pray for their children’s health or for safe labor on the stone jizo (guardian deity of children) that line the shore. Rend this flinty shell and you’ll be rewarded with a salty, savory treat just as surely—and maybe even a pearl or two.

Many women visit Jizo-hana to pray for their children’s health or for safe labor on the stone jizo (guardian deity of children) that line the shore. Rend this flinty shell and you’ll be rewarded with a salty, savory treat just as surely—and maybe even a pearl or two.

Nominally at a population just shy of 150,000 souls, Onomichi has that immediately recognizable feeling of decline that greets the frequent traveler of Japan’s small places, the lees of depopulation. The station is bustling, but only just; it doesn’t take long to notice the old fishing boats rotting in the harbor along the waterfront boardwalk, or the long-shuttered and vacant storefronts on the shopping arcade, empty windows staring dustily at the lonely street. The geography of the place is such that a walk into the hills forming the edges of the town initially recalls a scaled-down San Francisco. That nostalgia quickly fades, though, as one begins to notice caved-in roofs and tarps flapping obscenely— blue scabs on a wound that may never heal. The windows boarded over and yards overgrown have yet to outnumber the nicely kept bulk of the housing, but they are encroaching, and lend the city an aesthetic of their own.

The remnants of an old Japan reveal a ghostly experience.

The remnants of an old Japan reveal a ghostly experience.

Though Onomichi may have been the “birthplace of banking” in Hiroshima prefecture in the early 20th century, it is more recently famous for the unlikely trio of ramen, ancient temples, and woven sailcloth goods. Except for avid fans of “regional cuisine,” the ramen might be better skipped; it has the feeling (and taste) of one of those phenomena for which people will queue simply because people are queuing. The handmade canvas bags and accessories, however, are worth a look: an elegant, rugged simplicity ensures their popularity (something the trendy Onomichi hanpu label certainly doesn’t dissuade.) The temples, likewise, make for a lovely walk through quiet back ways.

Stepping out of the central shopping arcade and exploring one of the many alleys, though, is the best way to stumble across the town’s unique and delightful places. One noteworthy chai salon—Dragon—is an unpretentious shop fronting one of these alleys. Butting against the adjoining stores’ old black clapboards, the confusion of concrete, corrugated siding, and beat-up wood counters would be distressing if it weren’t all so elegantly tied together. Simple fabrics draped across the ceiling diffuse the light coming in and softens harsh edges; a spray of gravel is used to surprising effect under the rough hewed display shelves at the back.

Hiro, the shop’s owner, works in a Spartan kitchen, ladling hot water from a cast iron pot onto a sub-continental blend of richly aromatic spices. The fragrance of cardamom, ginger, cinnamon, and cloves fills the air as he talks about his shop.

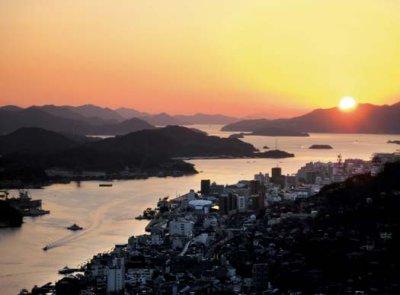

The Seto sea, dotted with countless islands, makes for a stunning view.

The Seto sea, dotted with countless islands, makes for a stunning view.

The idea for his venue sprang, he says, from a dissatisfaction with the overwhelming prevalence of chain stores. “You can go in, and it’s nice, and they greet you in a friendly way...but it’s all just empty style, a surface. The greetings are robotic and the menu is impersonally dictated by the head of the chain.” Hiro wanted to make a place for the same thirsty customers that visit these chain stores, but also to provide something they can’t: communication. And not just idle talk, either. Hiro acts on this communication, so a customer’s idea can actually make its way from napkin sketch to product.

This, in fact, is how Chaider was born. An interesting combination of a Japanese “cider” (a sweet, carbonated drink, though his isn’t nearly as sweet as other popular brands of cider) and green tea (hence cha), Chaider is a novel soft drink in a country where one wonders if they haven’t tapped every idea available. “Try proposing something like this at a drink company, say a company making cider or green tea, and the higher-ups would shoot you down immediately. Which is why it was a great opportunity for me to communicate with that customer, and get the idea out there, starting with a small-scale product.” And for now it remains small-scale, despite the attractive package (two elegantly labeled bottles wrapped in a traditional furoshiki folding cloth). Hiro is hoping for further cooperation from a larger beverage manufacturer or investor, as he believes his invention works on a cultural meme and is likely to take off with the proper support.

Back down the shopping arcade, Eiji is the proprietor of Yes, an unlikely “bottle bar” tucked into the third and roof floors of a ramshackle building. Winding through two nice shops (a clothing store and a café) to get to it is part of the point, he says, “I like being hidden up here, and surprising people when they happen across it.” The bar is another re-used building, his hideaway self-renovated to a brilliant grunginess that never feels dirty. Utilizing it as part café and part personal atelier, Eiji says that he chose Onomichi largely for the crowd that it attracts. “The art-inclined people that visit are so interesting to interact with, and I feel like that’s something fairly unique to this town.”

Walking through the back alleys leads you to unique little shops and cafés.

Walking through the back alleys leads you to unique little shops and cafés.

Onomichi does in fact draw a unique crowd (who even settle here, in many cases, and open their own cafe or bar or gallery), and places like this are ideally suited to it. “Embodied energy” is a word gaining attention recently, an accounting methodology used to describe the energy utilized in a structure, from the fuel and materials used in erecting the building, to the energy required through to demolition, even though it may still be perfectly adequate for use. Places like Onomichi are powerful proof of the value of embodied energy, both in the physical structure itself, and of the psychic imprints there of how many thousands of revelers, shoppers, lovers, patrons; something uniquely salient in these old places, and painfully absent from those that simply raise a structure from the foundations and age it 40 years in a week of careful interior decoration. The latter might look good but there’s something so essential missing that it often takes an act of will to look around that absence and enjoy the atmosphere for what it is, rather than drink all evening lamenting it for what it lacks.

At first glance just another fading town, Onomichi rewards the persistent explorer with a surprisingly cosmopolitan crowd and a delightful array of shops and other diversions. Those seeking something outside the ordinary would be well served by a visit.

| Contact Information: | |

|

Chai salon Dragon 1-9-14 Tsuchido Onomichi, Hiroshima www.atelierdragon.com 084-824-9889 |

Hand craft and bottle cafe YES 3-13 Higashi-gosho Onomichi, Hiroshima |

Comments

Martin (not verified)

November 10, 2008 - 14:04

Permalink

Onomichi article by Benjamin Brown

Beautifully written, informative and interesting article. Would like to see more articles from this writer of great talent.

Unbiased views of Japan's culture with local perspectives translated richly. Well done!