Caught in the Web

By Chris Salzberg

The day Japan’s netizens turned news on its head.

The massacre on June 8 in Akihabara ended with seven killed, more than a dozen injured, and an entire country in a state of shock. It also signaled a profound change in the way people receive their news, and in how they create it.

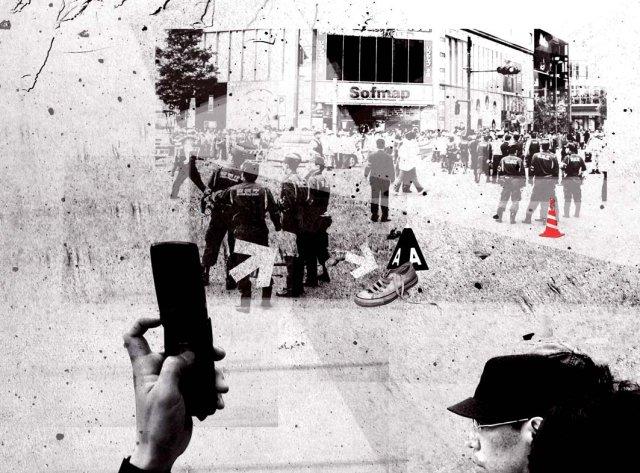

Illustration by Phillip Couzens; Original Photograph by Kawataso.

Illustration by Phillip Couzens; Original Photograph by Kawataso.

"Do you enjoy shooting videos of people’s misery?"

It was June 8 in Tokyo’s technology mecca, and the words of warning from a police officer fell on deaf ears. Armed with the latest in digital technology and lured by a morbid sense of curiosity, crowds of onlookers converged on to a blood-strewn intersection of Akihabara, amid firetrucks and ambulances, closing in to get a clear shot. Never before had so many eyes and ears shared in such a moment.

“It was really vivid,” one of those behind the cameras would later write in his blog, recalling the scene he had broadcasted to thousands just after 1pm that day. Only half an hour earlier, 25-year-old Tomohiro Kato, in one of the most sensational killing rampages in Japan’s recent history, had plowed a rented truck into busy shoppers along Akihabara’s pedestrian mall on Chuo-dori road. Stabbed with a combat knife in the ensuing rampage, many of those on the streets were in a critical state. “People right next to the camera were so badly wounded they were receiving resuscitation,” the blogger wrote. “There were towels to stop the bleeding all over the place.”

It was a scene the likes of which households across the country, tuning in to live coverage of the massacre, would never see. Broadcast without gatekeepers and shared across mobile networks, the images, video, and words that exploded onto the Japanese cyberspace on June 8 would become one of the most powerful examples to date of the country’s emerging net culture.  Emergency workers survey the scene of the stabbing as onlookers watch. Photograph by Kawataso. For the lost generation of twenty- and thirty-somethings, technology had opened a window into the tragedy in Akihabara that went beyond portrayals in newspapers and on TV. If this window was the new face of media, it wasn’t pretty but it was very direct, and very real.

Emergency workers survey the scene of the stabbing as onlookers watch. Photograph by Kawataso. For the lost generation of twenty- and thirty-somethings, technology had opened a window into the tragedy in Akihabara that went beyond portrayals in newspapers and on TV. If this window was the new face of media, it wasn’t pretty but it was very direct, and very real.

The moral perils of technology

The Akihabara massacre marked a major step in the changing relationship between Japanese people and their technology. Over the years, cultural differences in the way that people in Japan interact and form communities have had a profound impact on the local adoption of new technologies.

Rejecting many of the tools and services that countries in the West take to be universal, Japanese have favored trusted domestic brands, closed networks, privacy and anonymity. Facebook and MySpace, the world’s most popular social network services, barely register a blip on the radar in Japan. The iPhone is making waves across the world, but sales locally have, to date, been dismal. The rollout of Google’s Street View service, which allows users to survey cities at street level through three-dimensional photography, has been greeted by many with outrage and criticisms of cultural insensitivity. The contours of personal space on the Japanese Net are complex and subtle, but they can be decisive.

So when stories of people crowding like paparazzi around bleeding victims made their way from the streets of Akihabara to people around the country, many were shocked. The weekly papers were quick to react, running articles lambasting the indecency of the Akihabara mobs. The weekly Shukan Shincho featured the story of a university student whose two friends had been killed in the rampage, surrounded by onlookers snapping photos of their suffering. In his Mixi diary, the student railed at the picture takers for ignoring his pleas to stop. “Why did they do it?” he wrote. “It was so horrible, I couldn’t stop crying.” But the mobs persisted, clamoring for the best shot, dodging warnings by police to snap pictures and share them with friends.

Live streaming the massacre

Two of the onlookers in the crowd, meanwhile, pushed the limits to a new level. At 13:09 on June 8, just half an hour after Kato had been arrested, a message appeared in a chat room with the signal, “I started it.” Viewers in the room who followed a link to a channel on Ustream, a streaming video site, were transported to the site of the massacre, just as police were cordoning off the intersection where victims had been stabbed only moments earlier. Facing away from the sky blue sign of Akihabara’s Sofmap megastore, a programmer named Kenan turned on his digital camera and began recording the scene, in real time. Before long, the Ustream link was up on Internet mega-forum 2channel, and the number of viewers on the channel began to climb—fast.

Kenan was not alone. Another Ustream user named “Lyphard” was hanging around with friends nearby when the massacre began. “We were just chatting about whatever,” Lyphard explains “streaming our conversation on Ustream using a laptop, a Web camera, and an Emobile card.” Mobile phone operator Emobile had launched its 7.2 megabit-per-second high-speed wireless card only months earlier. Plugged into a laptop with a digicam and browser pointed to a user’s Ustream account, the card made it possible for anyone to walk down the street, laptop in hand, broadcasting live what they saw to far-away viewers.

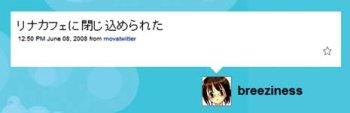

The first Twitter message to come from the cafe. It reads ‘I’ve been trapped in Linux Cafe.’

The first Twitter message to come from the cafe. It reads ‘I’ve been trapped in Linux Cafe.’

That’s what Lyphard did on June 8. Sitting in Linux Cafe, a hangout among Akihabara’s tech crowd, he and his friends chatted to each other and to their Ustream audience. “After about 15 minutes, the café suddenly became dark, and the shutters were closed,” he says. “From chat on Twitter and Ustream, and conversations in the store, we learned that there was a killer on the streets.” Frustrated that his Emobile card had stopped connecting, Lyphard told his friends that he was “just going to have a look,” and stepped out of the café, whereupon the signal returned. “Once I had set up broadcasting on Ustream and entered the URL into Twitter, I headed to the scene.”

In his blog gunnyori, Lyphard later described what he had seen that day. “Crowds. Ambulances. Police cars. Fire engines. Green tarps to hide things. Low-flying helicopters. Something red on the street. Policemen and paramedics working frantically.” Like Kenan, Lyphard watched as the number of viewers on his live stream shot up. “30, 50, 100, 400, 1000...and then it topped 2000,” he wrote. Just over 30 minutes in, the load became too much and the live stream eventually cut out. It was only when he was riding home on the train that he learned from a friend that someone else had also live-streamed the scene of the aftermath.

Being the media

In the days following the massacre, ethics of the Ustream coverage became the focus of debate in the Japanese blogosphere. In his own blog, Kenan expressed how he had felt “very excited” at the moment when his stream had topped 1000 viewers. “It was really fun,” the blogger wrote on the evening of the massacre. “There must be some cameramen who get the same kind of feeling.” Responses were swift, some of them supportive, some of them fiercely critical.  A screenshot from blogger Lyphard’s live streaming of the murder scene. Image courtesy of Lyphard. An early comment quoted from the Bible, warning Kenan that he would go to hell for his actions. Another simply told him to die. “So when you get stabbed and you’re mortally injured,” another wrote, “I guess you’d be okay with someone taking a video of you and getting all excited about it, right?”

A screenshot from blogger Lyphard’s live streaming of the murder scene. Image courtesy of Lyphard. An early comment quoted from the Bible, warning Kenan that he would go to hell for his actions. Another simply told him to die. “So when you get stabbed and you’re mortally injured,” another wrote, “I guess you’d be okay with someone taking a video of you and getting all excited about it, right?”

Criticism came not only from the blogosphere and wider society, but also from those within the mass media. Toshinao Sasaki, a freelance journalist and author of a host of books on Japan’s Net culture, has written about the implications of the incident for traditional media. “Many in the media responded that it’s disgraceful and offensive to victims for individuals to be taking pictures of the scene,” he said in an email. “The thinking is that whereas the mass media bear a responsibility for the effects of their reporting, issuing corrections when there are mistakes, no such responsibility applies in the case of reporting by individuals.”

“While mass media despise the actions of individuals, they are also personally threatened by them.”

But this was not the only reason the mass media were critical. “The rapid rise of news reporting by individuals,” Sasaki explains, “also leads to a sense of impending crisis in the mass media, because it seems to them that their own position is in jeopardy.” Underlying this sense of crisis, he says, is the leveling of differences between institutions and individuals on the Internet. “While mass media despise the actions of individuals, they are also personally threatened by them.”

A changing relationship

Nowhere was the conflict in the media’s attitude toward the keitai-camera mobs more evident in Akihabara than in one of the most famous pictures to emerge from the tragedy. Appearing on the front page of the Mainichi Shimbun newspaper’s evening edition on June 9, the shot featured Kato in handcuffs as he was escorted into a police car, the caption crediting the photo as having been taken by a “passer-by.”  The Mainichi Shimbun newspaper ran this photo on its front page. The picture, taken on a cellphone, and spread among the crowd via infra-red was attributed to a “passer-by.” The identity of the photographer, the newspaper later explained, was unknown: taken by someone in the crowd and passed on from person to person via infrared file transfer, the photo eventually made it to a reporter from Mainichi, by which time its origin was unclear.

The Mainichi Shimbun newspaper ran this photo on its front page. The picture, taken on a cellphone, and spread among the crowd via infra-red was attributed to a “passer-by.” The identity of the photographer, the newspaper later explained, was unknown: taken by someone in the crowd and passed on from person to person via infrared file transfer, the photo eventually made it to a reporter from Mainichi, by which time its origin was unclear.

A one-time reporter for the Mainichi Shimbun himself, Sasaki highlights a dilemma in the newspaper’s decision to feature the photo of Kato. “The use of photos by eyewitnesses in the pages of newspapers has been going on for a long time,” he explains. “However, as the Internet advances and people start posting photos in their blogs, newspaper companies respond by criticizing them for going around taking pictures of whatever they like.” And it is here that newspaper companies expose a double-standard, he says, since they themselves have used similar photos throughout their history, without permission. “Companies criticize picture-taking by individuals, so they end up contradicting themselves,” he says. “Caught in a web of their own making, as they say.”

If the changing relationship between technology and news came as a shock to those in the mass media, however, it also came as a shock to those behind the digital cameras, who suddenly came under intense spotlight. Faced with criticism at his blog, Lyphard took days off work for mental recovery. His views about what happened on June 8, however, remain unchanged to this day. “It wasn’t that I wanted to be the mass media or something,” he insists. “I was just doing the same thing I do all the time, streaming video on Ustream.” About his motivations, he is adamant. “It’s just a hobby, like the father taking a handicam movie of his child, or filming the scenery. There’s nothing more to it than that.”

When everybody is a reporter

But a line was crossed in Akihabara on June 8, and many in Japan’s blogosphere felt it. Akihito Kobayashi, blogger and consultant at Hitachi Consulting, wrote about the need to contemplate a future in which everyone is a potential news reporter. “It was when I saw all these people transmitting reports from the scene of the massacre that I realized the scale of what had become possible through the Internet,” he commented in an email. “It didn’t stop me from blogging, but I do have the feeling now where I hesitate for a moment before pressing the publish button, and think to myself: is there a chance that these words could hurt someone?”

Clay Shirky, one of the most well-known commentators on Internet technology, remarked recently that “communications tools don’t get socially interesting until they get technologically boring.” In other words, it is only when a technology gets out of the way, when it fades into the background, that the technology’s impact on society begins to emerge.

The tragedy in Akihabara came as a shock to Japan and to the world, but it also brought out a social impact in a way that this country, deeply intertwined with its technology, had never experienced before. Heading into an era in which everyone becomes a part of the news, it may ultimately turn out that this experience offers the most sobering insights about the future.

Comments

Willie (not verified)

November 21, 2008 - 10:19

Permalink

Japan's a bit slow on the uptake?

This argument has long been running in other circles, and it seems to me that Japan might be a little slow on the uptake with this debate.

The fact is that the media in Japan is a very closed loop cirlce, and while I maintain that professional journalists have to abide by the ethics of their profession, it's unfortunately true that in today's media landscape even they are finding that blogs are a more democratic way for them to report the news.

As more of the world's media are owned by less and less people, we end up with news that is bland, superficial and very much in want of balance. I don't think that the people who filmed what was going on in Akiharbara should be made to feel bad for what they did. They were simply reporting, and reporting should not be the bastion of the journalist alone. They are not paramedics, so they should not be interfering with the care of the victims, but as witnesses to an event, their recording of what will historically become a dark day in Japan's history will reveal itself as both useful and important, I don't doubt.

The debate of the blogging phenomenon has been raised again and again throughout history one one way or another. What people need is more education on media - all forms of media - and how to become discerning consumers of it. Clogging allows the media to become an interactive forum, and the mass media are freaking out because they know it's hurting their bottom line. Just ask Rupert what he thinks, and he'll tell you that those in the media who don't embrace the immediacy and interactiveness of the Internet will just roll over and fade away.

In regards to whether or not people in distress or trauma should be photographed or videoed, this debate is also very much present in the professional journalist world too. A classic example is the photograph taken by Pulitzer Award winning photographer Kevin Carter, who took the picture of the Sundanese boy being eyed by a vulture. Although he won the greatest journalistic prize for the photo, which also raised awareness of the Sundanese problem, Carter suffered depression for months afterwards before he committed suicide. According to Carter, there were aid workers close by, so there was nothing he could personally do, but he did not know what happened to the boy. Many people criticised him for taking the picture.

And so I leave with this question: what happens when people stop being observers of their own world? What happens when the only people who are 'allowed' to observe are connected to an institution that only allows them to observe what they're told to? this si the question that needs some deeper thought from everyone.

Chris, you have written an excellent article, and thanks to Japan Inc for running it.

Someone (not verified)

November 21, 2008 - 13:00

Permalink

What happens when ...

Not a deeper thought - another thought:

So far - especially during the past 50 years of news on television - people have not been observers of their own world. Also good old print media has not been any different. Only people who were 'allowed' to observe made the news. What we have experienced over and over is for example controlled misinformation (lies) to win majorities of a nation to support war. The list of abuse is endless, and journalistic ethics has not prevented it. And that is what we have had so far.

So, I think it will be the other way around: Now people start being observers of their own world. It will be unstoppable, unless we ban mobile phones with built-in cameras, other gadgets, and the Internet - which is unlikely.

Of course, also these new possibilities have been and will continue to be abused in all possible ways.

However, most people are taking photographs/videos/stories of good things and show them on Internet.