How Gaijin is my Kansai?

Back to Contents of Issue: December 2002

|

|

|

|

by Alex Stewart |

|

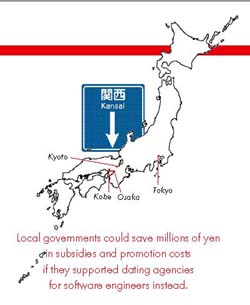

The "sai" in Kansai means "west." In the US, the sense of frontier and newness is in the west, but in Japan, it is largely in the east, in Tokyo. The exception to this rule is the foreigners who sally west to Japan's Kansai. They must have the frontier spirit to want to build a life and a future in Kyoto, Osaka or Kobe. I decided to find out. The "sai" in Kansai means "west." In the US, the sense of frontier and newness is in the west, but in Japan, it is largely in the east, in Tokyo. The exception to this rule is the foreigners who sally west to Japan's Kansai. They must have the frontier spirit to want to build a life and a future in Kyoto, Osaka or Kobe. I decided to find out.There are elements of a West Coast spirit in Japan's Pacific West, but sadly it fails to reach its potential due to the weak multicultural infrastructure and the lack of opportunities to grow rich. It is hard to find a rich gaijin in the Kansai. Yet there are always exceptions. When Japanese say "gaijin," they mean Westerners, not people from Asia. Yet the real action in software is among the Chinese, Indians, and to a lesser extent, Korean entrepreneurs who are setting up software companies in the Kansai, generally to provide outsourcing services. Indian companies are especially active. The gaijin software entrepreneurs are fewer in number and less well organized, but they have more impact because they are able to relate more easily to what is happening in the US, introduce new thinking and help influence change. The Asian software entrepreneurs are like the early Japanese selling consumer electronics products in the US: staking a toehold in what seems a vast and profitable market. The reason gaijin software entrepreneurs are here has a more basic root -- they are following a woman, or so it turned out in almost all of my interviews for this piece. Mostly this means they are hitched to a Japanese spouse, and sometimes it is "the girl from Osaka I met on my travels." It's a rather crude generalization, but only half-jokingly, local governments could save hundreds of millions of yen in subsidies and promotion costs if they re-directed their efforts to support dating agencies for overseas software engineers instead. Support for internationalization among government agencies and corporations, especially in places like the Kansai, is strong. The gaijin software entrepreneurs should be the shock troops of this movement, having the best insight into one of the main sources of internationalization -- the IT revolution. David Leangen, founder and CEO of Konova Solutions, a software company developing advanced search tools for data mining, spent a year at the massive development center of an electronics company on the outskirts of Osaka. He was highly skeptical of how the company chose to use foreign talent to internationalize their operations. He explained that he was one of 10 foreign interns among 10,000 Japanese. Most of the interns had little to do, he said, except to be featured in publicity shots that made the labs look like a hive of multinational activity. But Leangen acknowledges that the company did give him his break, as it turned out, letting him develop software which they had licensed but were not developing. Many of the other gaijin software people interviewed mentioned that while their ideas were not openly acknowledged, just as often they would find them incorporated, without attribution, into the company's planning model. Foreigners, therefore, are utilized, but not immediately embraced. Lack of risk capital and the absence of a risk-taking spirit are the other missing ingredients from a foreigner's perspective. Leangen points out the difficulty of raising money. As it happens, Konova won J@pan Inc's business plan competition at the end of 2000 -- when money was still growing on trees. It helped them get more meetings with foreign and domestic venture capitalists, but they were still considered outsiders at every turn, he recalls. The Kansai is not cosmopolitan, not very receptive, and doesn't have much money. So what is left? The size of the market and the depth of opportunity. As Leangen acknowledges, the market is several orders of magnitude larger than Canada, so if Konova can break in, it will pay off. There is also technology. Ian Shortreed, owner of Kyoto-based Mercury Software, observes, "There is more technology in this valley than anywhere in Japan." The "valley" is Keihan Valley ("Kei" is the reading for Kyoto and "Han" for Osaka). Like Silicon Valley, it is based on the semiconductor industry, but unlike the Valley in the US, it has yet to acquire a broader software base. When it comes to advanced semiconductor materials, fabrication equipment, microchips and miniaturized parts of any kind, however, Keihan Valley is probably the world leader. Key to any discussion about Kansai, software and foreigners is Kyoto Research Park. Jeffery Hensley, international business development manager at the Park, organized a meeting for me there to discuss the foreign presence in the area. The park often seems the one obvious beacon of hope for creating a Silicon Valley infrastructure in Kansai. Hensley says his goal is "to have at least laid the groundwork" for a 10 percent ratio of foreign tenants within the next four to five years. There are currently 183 tenants in the park, he says, and six foreign-affiliated firms in areas ranging from IT to DNA synthesis. Jeff has a lot of work ahead of him, but his vision flickered to life that evening at least, as seven of us relaxed in the Park's beer garden, filling the night air with foreign voices. The absence of a good networking structure was a key issue for all at that Kyoto meeting. Various networking groups have sprung up in the Kansai since the 1980s. The most established is the Kansai Mac Users Group (K-MUG). More recently, the growth of opportunities in the Internet space encouraged David Moskowitz, a young American who runs a keitai software development business called "i-Kaiwa" from his home in Osaka (and teaches English to pay for it), to establish an online community that also meets for networking purposes. CLICK! now has 40 members but still lacks a good meeting place, and consequently meetings are sporadic. There are not enough IT gaijin in the Kansai. Those like Ian Shortreed probably make up for their shortage in numbers by their dynamic lifestyles. Ian is a native of Canada and a 23-year veteran of Japan, mostly in software. He has an infectious enthusiasm for the latest in software and IT -- anything good "rocks" in his vocabulary. He had just returned from a visit to the Apple shrine (read HQ) in Cupertino, California, and was "rocking" with ideas about 802.11 Wi-Fi and weblogs. For Wi-Fi (the free FM 802.11spectrum used as a high bandwidth wireless medium -- "very radical, very hippy, the original spirit of the Internet"), Kyoto could be a good place to launch a business, which would give its IT infrastructure a further edge. Shortreed could be the point man: The local government and IT advisory groups routinely seek his advice, so he is plugged in, even if he does his business only in Tokyo -- "I don't do any business in Kyoto; I get my batteries recharged in Kyoto." He doesn't do his coding in Kyoto either. He gets that done in China.

Shortreed describes Kyoto as "the West Coast minus the sea," but I consider the most exciting (though not scenic) place in the Kansai to be Osaka. Both Kyoto and Kobe exude definite cool, which attracts design people. Kobe, for example, feels almost Mediterranean, and combines this atmosphere with a Chinatown that creates a cultural diversity unique in Japan. Kyoto is the defining place of what constitutes Japanese style, but it is a bit placid and laid back. For the real city buzz and action, the place in my book is Minami-Semba and the areas around it in downtown Osaka (see Digital Osaka in the November 2002 issue for more on this take). Kyle Barrow, a New Zealander, and his wife, a Japanese fashion designer, run a 5-man design company called X-9 in the area. He describes where he lives as a cross between Tokyo's trendy Harajuku and Omote-Sando neighborhoods. An associate of mine based in the area says that according to the real estate industry a new restaurant opens every week (and probably another one closes). With the long-running recession, the cost of renting is still not a major issue. Barrow and his wife have owned an apartment in the area since 1998 (getting in just before Minami-Semba got red hot, he says). When they took on two more graphic designers, they "maxed out" at the home office, but found space within a 20-second commute across the street. As Barrow explains, "To live and work like this would cost three times for the same deal in Tokyo." So the Kansai has lifestyle, design and cost of living advantages, but it still isn't enough to bring a tide of gaijin entrepreneurs from the Big Tatami Mat. What's missing is critical mass: There just isn't enough of a network to create a mini-Manhattan or Soho. Besides, if someone is going to leave Tokyo, Barrow observes, why come to another mini-Tokyo? More likely they will want to move into the real countryside. Conversely, I have not come across foreign software folk in Kansai moving to Tokyo. The nearest was Osaka-based Silver Egg Technologies, which seemed close to moving to Tokyo when it was being lifted by the bubble toward a listing on Mothers or Nasdaq Japan. In its day, Silver Egg was a darling of the Internet crowd, raising money from, among others, Internet guru Joi Ito. From the middle of 2001 it had cut its work force, which had reached 30 or more. Unlike many of the Internet pioneers, however, it did not crash and burn. Thanks to some deft management, the owners -- Tom Foley and his wife -- managed to retain the corporate entity and the office in Osaka, with most of the equipment. When I met Foley for the interview, he looked happier and more energized about the future than ever, and this in spite of nursing a summer cold. "We've gone back to our roots in software development," he said cheerfully. Osaka is ideal for doing this, since he can write the code anywhere, and Osaka (or more precisely the Kansai) suits him much better from a lifestyle point of view. His new business model is to sell his software as an ASP, so he can enroll and service customers entirely through the Web. Previously he sold his software as an installable software package, which required a heavy sales effort, mostly in Tokyo. The ASP model changes the economics in favor of operating with dramatically lower overheads and freedom of location, which is ideal for a startup. He is determined to prove his approach will work outside Tokyo. He calls it an "obligation." Silver Egg's software is designed to make educated guesses about a customer's buying preferences based on their clicking patterns as they move around a site. Kansai, as it happens, has several successful companies in the e-retailing space that could be customers. There is Magu Magu, for example, the leading e-zine aggregator and publisher, and Hon-ya, one of Japan's biggest online book retailers -- both are based in Kyoto. The new ASP product still needs to undergo full testing; Foley promises its release in the first quarter of 2003. Gaijin in business in the Kansai are less likely to be straight off the boat, and a big reason for this is the lack of a network of fellow gaijin. James McGuire, a young man from Seattle with the weathered expression of a Scottish crofter, is one of the exceptions. He first came to the Kansai area while backpacking around Asia. He acknowledges the "girl factor" in dropping by the Kansai while backpacking around Asia, but he also had a strong background in programming from the US, so he figured that finding a job in software would be a good reason to settle. "It was actually harder then I thought," he says. The company where he first found employment, called Yumemi ("yume" means dream; the company's slogan is "You may dream with me"), is a keitai software company that benefits from its close links to Kyoto University. It employs around 10 people full time and 20 interns (mostly from the university). The average age of the workers is under 23 years old. McGuire points to the talent among the college students, the raw thinking untainted by the corporate production mill. What is lacking, he feels, is a better incentive structure to get the individual to give more. He acknowledges that this is a US way of thinking but believes it would work in Japan too. He notes, though, that since he has been in the company the culture "is starting to change." The company declared over a year ago that English was going to be the official company language by April 2002. This must have been helpful when McGuire started, having arrived in Japan without Japanese. There are now six foreign interns (one each from Slovakia, Turkey, Indonesia and Colombia, and two from the US) but he is the only full-time foreign employee. "I'd like to see more," he says, "but I think the company is hesitant because of increased salary demand and the added culture gap." For foreigners considering a move to the Kansai, it is worth noting the comments of executive search firm Oak Associates, which maintains a surprisingly busy practice in Osaka despite the poor economy. According to Heiko Haug, a German who is responsible for all IT appointments, the strongest demand is for software engineers with application skills such as those used in enterprise resource planning and supply chain management. He found that software gaijin in the Kansai generally had front-end Web programming skills for which it was harder to find job openings in large companies. The other problem is that employers want people who are likely to remain in the company for several years, and hiring a foreigner poses more of a risk in that respect. When it comes to a foreigner showing commitment to his Japanese employer, however, Robert Stewart, a real Scot, is a good example. He has worked six years for his company, ARDUC, which provides mainly network integration solutions for one major semiconductor company, though it is gradually expanding its customer base. He says he has a free hand at the company to develop ideas, although his business card describes him as "assistant manager, System Sales Division." His current focus is to go after foreign accounts. He has three North American software engineers reporting to him, and there are four Chinese staff -- two in Shanghai and two in Osaka. Stewart thinks he might feel more restricted returning to work in a UK software company: "It could be too disciplined; here I work flex hours -- if there's no work I can leave." He acknowledges that the stilted language of keigo (honorific language used with superiors) is used but says, "I feel I can talk to anyone in the company, right up to the top; there is professional respect for your job." Even rarer is the case of the foreigner tapped overseas to come and work in Kansai. Steve Burkholder was recruited in the early 90s to open the office in Kyoto for Britannica International (English schools, textbooks, CD-ROMs, e-commerce, encyclopedias) straight from studying international relations and Japanese business at the University of Washington in Seattle. Britannica headed increasingly into the Internet space from 1995, helping Burkholder became familiar early on with Net strategies. He felt settled enough by 1996 to build a family home on the shores of Lake Biwa, north of Kyoto. The bursting of the Internet bubble forced Britannica to close its Kyoto office in 2001. It took Burkholder longer than he expected -- five months, to be exact -- to find his eventual employer, J-Data. He landed the job by a combination of searching online job sites, using a family connection and getting help from a third party. J-Data was planning to go global, so Burkholder was in the right place at the right time. Although he claims his Japanese is only reasonable, he clearly has the awareness of how to work in a Japanese company and retains the broad smile of a West Coast American who views the future optimistically. J-Data was also an exciting find for me. At the time of our interview it was just rolling out a service called WebNum (http://www.webnum.ne.jp). WebNum is a service of VeriSign in the US, which is arguably the Internet's best placed infrastructure company, controlling key connection points on the Web as well as the management of the Web domain name system, such as .com and .net. The WebNum system allows users to key in numbers on the keitai pad that have been chosen by subscribing companies to be "memorable, brandable numeric short cuts," enabling the keitai to link directly to the subscribing company's Web site via the global domain name system. As an example, it is much quicker to key in "Honda" by hitting "46632" than to input the company's Web site address by the phonetic key method. WebNum's power is that it has scalability to millions of Web sites because it connects directly to the global domain name system. WebNum tied up with J-Data ( the exclusive distributor in Japan) because of its venture spirit and the fact that it had developed its own number access system called "Bango," according to Burkholder. He is in charge of the international department, coordinating with VeriSign in the US. Things are moving fast now: WebNum has been available on the KDDI Kantan Access menu since October and is due to launch on J-Phone's J-Sky service soon. J-Data, with just 15 employees, is a future IPO candidate. Stock options are available, which no doubt helps to sustain Burkholder's focus, as well as making communication with the VeriSign culture in the US easier for all. There should be a way to use the Internet unite the under-used talent around the world with the latent demand in Japan. Gaijin software entrepreneurs have shown some ways to help bridge the gap. However, Mike McKay, a Californian, thought he had a better answer when he started WorldnetJapan in 2000 to broker work for Internet professionals looking for customers inside Japan. He arrived from San Francisco in 1999, married to a Japanese woman but unable to speak the language himself. He had the requisite experience as a Web designer and began finding clients mainly in Kobe, where he is based. Despite heavily promoting his service through various Internet channels, he ran into the problem of the economic meltdown, the difficulty of communication and the weak risk-taking spirit. He has found arguably the best solution to the problem of communication and the Internet: McKay distributes a newspaper called Easy English NEWS, designed to help readers learn English online. Worldnet is a small piece of the big Internet puzzle, which companies like VeriSign help to order and organize. It is also a small illustration of the frontier spirit. The entrepreneur in this case went farther than most and kept pushing west from San Francisco to reach Kobe. It seems an unlikely landing place for an Internet entrepreneur, but in this borderless world, one of the lessons from a survey of gaijin software talent is that businesses can start up anywhere through the Internet. Small software-intensive companies like Silver Egg can develop their potential in the rolling hills of Hyogo as easily as in Tokyo. Opportunity is everywhere if you know how to take it. But ... it does help to have English language teaching to fall back on if everything goes horribly wrong. @ Alex Stewart is a contributing editor to J@pan Inc. His most recent article, Digital Osaka, appeared in the November issue. He is not currently teaching English. |

|

Note: The function "email this page" is currently not supported for this page.