Japan Does Burning Man

Back to Contents of Issue: December 2002

|

|

|

|

by Debbi Gardiner |

|

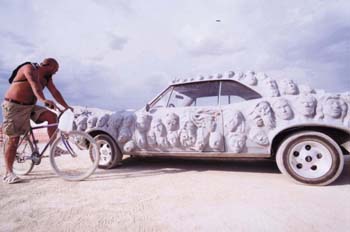

Kazio Nishima arrived at Black Rock City in the Nevada desert an hour ago. He has already set up his tent. His friends have secured a Japanese flag to their SUV. An officer hell-bent on enforcing the no-drugs law is checking his tent for marijuana as I cycle over. This is the third year Nishima, a skinny and laid-back 26-year-old cyber-journalist, has ventured out here from Tokyo for the annual Burning Man event. He says it's the sense of freedom that has him hooked. "This is a complete rebellion against corporate life," he says. "There's nothing like this in Japan." Kazio Nishima arrived at Black Rock City in the Nevada desert an hour ago. He has already set up his tent. His friends have secured a Japanese flag to their SUV. An officer hell-bent on enforcing the no-drugs law is checking his tent for marijuana as I cycle over. This is the third year Nishima, a skinny and laid-back 26-year-old cyber-journalist, has ventured out here from Tokyo for the annual Burning Man event. He says it's the sense of freedom that has him hooked. "This is a complete rebellion against corporate life," he says. "There's nothing like this in Japan." Nishima has more to say but a sandstorm blows in, forcing me to flee. I take refuge in a port-a-potty until the dust settles. This is Burning Man, the world's biggest and wackiest annual summer camp, where artists, performers and business professionals from all over come to frolic, commune with nature and forget corporate life during the last week of August. What began in 1986 with 20 participants at Baker Beach in San Francisco has grown to a record 29,000 revelers this year. Burning Man is an art festival. Revelers build machines, "art cars," perform their music, paint one another's bodies and offer services such as meditation, showers and cool refreshments. It's also a rave. Revelers hold frenetic parties, climaxing with a group burning of an 80-foot wooden man and a stunning temple the size of a small airport hangar. It's all about radical self-expression. In its 17th year, in spite of a world recession, Silicon Valley's dot-com bust and terrorist attacks, Burning Man is still going strong. Many participants come from nearby Silicon Valley, but a healthy contingent also comes from Japan each year. Nobody really tracks the numbers, but Tokyo-based photographer Vincent Huang, who introduced the gathering to Tokyo folk by publishing his book of photographs called Burning Man, thinks over 200 attended this year. Burning Man has also grown as a social group. More than 60 regional contacts represent almost every state in the union and several countries overseas. Maki Hirose, a corporate seminar writer working in Tokyo, says she and her friends are working on a Burning Man in Japan.  From the onset, Burning Man has attracted a lot of people in the tech world. Time once referred to the gathering as "bonfire of the techies." Participants, known as "burners," are an eclectic breed of engineers, lawyers, programmers, performers, bartenders and artists. According to the 2000 Black Rock City Census, the median income of revelers is around $40,000 a year, and almost half of the participants work over 40 hours a week.

From the onset, Burning Man has attracted a lot of people in the tech world. Time once referred to the gathering as "bonfire of the techies." Participants, known as "burners," are an eclectic breed of engineers, lawyers, programmers, performers, bartenders and artists. According to the 2000 Black Rock City Census, the median income of revelers is around $40,000 a year, and almost half of the participants work over 40 hours a week.Part of the reason business professionals make up such a large part of this summer party is that the barrier to entry is so high. Burning Man is expensive. Tickets range from $185 to $250. And then there are the costumes, which can be more glamorous than the ones in Brazil's Carnival. Ladies build elaborate headdresses with plastic birds and gigantic fabric flowers. Guys spend their pennies on building machines. My boyfriend, a structural engineer, spent $500 on a go-cart he built from a supermarket shopping trolley. Then there's transport and supplies. Nishima, the cyber-journalist from Tokyo, says he spent $2,000 on Burning Man this year.  Burning Man is not for the weak-willed. Camps are jammed. Nightclub techno music blares till dawn. The only commodities that can be bought here are coffee and ice. Everything else is bartered. Getting sorted with food, shelter and water means getting organized and savvy. Our tent was sweltering by 9 am. Our water supply permitted a solar shower every two days. And then there are sandstorms.

Burning Man is not for the weak-willed. Camps are jammed. Nightclub techno music blares till dawn. The only commodities that can be bought here are coffee and ice. Everything else is bartered. Getting sorted with food, shelter and water means getting organized and savvy. Our tent was sweltering by 9 am. Our water supply permitted a solar shower every two days. And then there are sandstorms. "If you weren't ambitious, you wouldn't be here," says a burner who wants to be known as Paul, shiny with sweat and uncomfortable in long pants that he can't relinquish because his pale skin burns easily. Nishima, the cyber-journalist, cycled to Black Rock from Reno. It took him three days in 40 degree heat. It was "taxing," he says, but he had a blast. Two Japanese software programmers working for a San Francisco game company arrive on Day Three. They bring little food, no shelter and insist on sleeping in their car. "We'll be fine; we're here to party and enjoy," they say. For hard-working techies, Burning Man can be liberating. For corporate workers it feels like an act of rebellion. By Day Two half my camp discards their clothes and runs around topless. By Day Seven half the girls are in the buff. In the desert, people take on new names. Chip Doring, an engineer with Philips, goes by the name of "Widget." Work is forgotten. What's hailed is audacity, how big a machine you can make, how flamboyant your outfit is or how big a flame you can shoot. In seven days I visit 12 raves, cycle through the desert day and night, and make new friends. I have a peppermint oil foot rub at the Solar Collective, an all women's camp, attend a disastrous yoga class (I'm a bit clumsy), puff on a hookah pipe in an Arabian tent, then get covered with silver paint. I watch men rollerblade in the nude and climb on board a pirate ship made by a Dutch carpenter named Ducky. Burning Man is also a creative hub. Its organizers are known as some of the country's most generous donors to artists. This year 200 works of art, all with a nautical theme, are on display. I see exquisite sea horses, wooden lotus flowers and wind chimes. And much of the art is Japan-esque. For instance, the Temple of Joy, a 78-foot-high artwork by San Francisco artist David Best, looks like a cross between a Japanese pagoda and a Thai temple. Best also joined with San Francisco architects to build a stunning Japanese teahouse. Every year Best's temples are burned down for the finale. This year the pagoda is swamped with visitors marveling at the architecture or leaving messages to loved ones and messages of hope for the next year. But beyond that, Burning Man is all about the feeling. There's something serene amidst the chaos, the cramped tents, gritty food, blaring loudspeakers and ravers. The 2000 census says that 22 percent of Burning Man revelers are agnostic or atheist, compared with 0.9 percent of Americans who say they are, implying that Burning Man for many fills a spiritual gap. On the first day posters on cars speeding up the highway to Black Rock City read "Welcome Home." "I feel at home here," says Hirose, the seminar writer. We meet at the Temple of Joy on Day Three. She looks spring-fresh in her Indian white cottons and a straw hat with dangly bits representing tentacles of a sea anemone. Hirose stayed in Tokyo during the Obon summer holidays so she could attend Burning Man in late-August. She freelances for banks and IT companies and says in spite of the physical challenges out here she can unwind. "People are free here so I can be as uninhibited as I like," she says. Huang, the Tokyo-based photographer whose book came out last spring, has been to Burning Man every year since 1997. He says he was inspired to make a book about the event because he's fed up with people thinking Burning Man is only about drugs, sex and music. "The spirit of the event is so much more than that," he says. Evidently, a growing group of Japanese workers agree. @ Debbi Gardiner is a regular contributor to J@pan Inc. Her last story, Women's Business, appeared in the November issue. |

|

Note: The function "email this page" is currently not supported for this page.