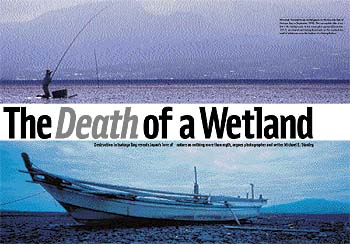

The Death of Wetland

Back to Contents of Issue: November 2002

|

|

|

|

by Michael E. Stanley |

|

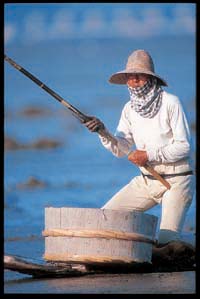

EDITOR'S NOTE: Japan, perhaps more than any other industrialized country, has relied for decades on public works as a way to spark the economy. For years, despite environmental sacrifices, the plan worked: Build a bridge, line the coffers of construction companies with government money, and keep the locals happy and employed. But lately, public works have been the target of criticism; moreover, they've been unable to recharge the nation's sputtering economy. As if oblivious to the public resentment toward some of its plans, the government plunges ahead with more pork-barrel projects. Is Japan being paved over to appease a government addicted to public-works spending? Are there any benefits to this spending that are being overlooked in the highly charged debates about government policy? To delve deeper into this issue, we are bringing you the first in an occasional series that captures the effects of Japan's public-works projects through the lens of a camera. EDITOR'S NOTE: Japan, perhaps more than any other industrialized country, has relied for decades on public works as a way to spark the economy. For years, despite environmental sacrifices, the plan worked: Build a bridge, line the coffers of construction companies with government money, and keep the locals happy and employed. But lately, public works have been the target of criticism; moreover, they've been unable to recharge the nation's sputtering economy. As if oblivious to the public resentment toward some of its plans, the government plunges ahead with more pork-barrel projects. Is Japan being paved over to appease a government addicted to public-works spending? Are there any benefits to this spending that are being overlooked in the highly charged debates about government policy? To delve deeper into this issue, we are bringing you the first in an occasional series that captures the effects of Japan's public-works projects through the lens of a camera.We have all heard again and again how much the Japanese culture is dominated by a love and sensitivity for the amazingly rich natural heritage of this archipelago. Perhaps that was true at some point in years past, but it is nothing less than an egregious lie here at the beginning of the 21st century. The professed love for "nature" is a worn-out, hollow clichE the patent falseness of which is evident to anyone who has tried to search out what truly remains of Japan's wild patrimony. The modern Japanese apparently prefer their precious "nature" controlled and neatly packaged, but the results -- manmade beaches, manicured golf courses and artificial amusement-park attractions -- hardly fit anyone's definition of "natural." The salient facts about the amazingly rich biota of these islands are taught to every schoolchild, but in truth the culture of modern Japan shows a single-minded willingness to sacrifice it all for gain, and this usually over a relatively short term -- and often off the books. A case in point is the story of Isahaya Bay. On the west side of Kyushu, the southwesternmost of Japan's four main islands, is a long arm of the ocean called the Ariake Sea. It is a shallow bay, rich with life. Isahaya Bay is on the Ariake's west side just above the Shimabara peninsula; the tidelands of this bay were until recently the largest remaining marine wetland in Japan and a major stopover for birds migrating between Siberia and Australasia. Moreover, as development devoured the coastline of the Ariake Sea, the importance of Isahaya Bay grew as a refuge for species unique to this special corner of the western Pacific. Two hundred and eighty two species of benthic fauna have been identified in the bay. But on April 14, 1997, a 7-kilometer dike closed off 3,550 hectares of these fecund shallows. Sixteen hundred hectares are slated to be reclaimed as agricultural land; the rest is to be a freshwater catchment reservoir. This project was first proposed in 1952 with the aim of turning the tide-washed mudflats into rice paddies to feed a Japan still reeling from the defeat of the Pacific War. Even though that need disappeared in the following decade, entrenched bureaucratic stubbornness and under-the-table cronyism eventually won out despite strident local protests, a growing awareness of the ecological importance of the bay and a JPY100 billion cost overrun. As rice-yielding acreage alone was no longer a sufficient pretext, pasturage for expensive wagyu beef cattle was substituted as a pressing reason for the project. When beef imports were liberalized in the 1980s and the bottom dropped out of that market, the project was then reincarnated for the purpose of flood control. Whatever the rationale, landfill and related construction continue; completion is forecast for 2006. In September 1996, I traveled to Isahaya to photograph the last season of mutsukake, a traditional technique of fishing used to take mudskippers (mutsugoro). These unusual fish are the northernmost representatives of their kind; their relatives prefer the warm estuarine shallows of the Indo-Pacific region. In all of Japan, they are found only in the Ariake Sea, and until 1997, the richest concentration of these odd, amphibian-like fish was found in Isahaya Bay. They are a delicacy and a symbol of the area. Hiromichi Harada, an Ariake fisherman, was my guide and subject. With him, I traveled out into the center of the tidal flats and was able to see the rich life of the bay firsthand. It was not an easy undertaking, as the gata (tidal mud) away from the shoreline is not firm enough to stand or walk on. Ariake fishermen move about on the gata using shaped planks up to about two meters in length on which they kneel and propel themselves by pushing with one leg. This technique -- imitating the movement of the mudskippers -- is quite common in the muddy estuaries and tidal flats of tropical Asia, but in Japan is encountered only in the Ariake. I had to do the same, with all the camera gear precariously loaded into a large wooden tub atop the plank. That narrow piece of lumber became my trusty vessel and work platform out on one of the most unusual corners of this planet that I have ever visited.  While the scenery was flat, wet and generally of a consistency between freshly poured concrete and barbecue sauce, the array of life was astounding. The small creatures were all hyper-skittish: The mudskippers, crabs and other fauna would hastily dive into their burrows at our approach, although after some minutes of motionless waiting, legs and eyes and fins would begin to reappear. The mud would come to life again, and Harada would begin his fishing, casting and snagging the mudskippers through their gill covers in one smooth motion that did not alarm the creatures enough to send them headlong into their hidey-holes. We had to keep an eye on the time, as the six-meter tides of the bay rise very quickly. I spent three days out on the farther flats, with the incomplete dike always looming in the background.

While the scenery was flat, wet and generally of a consistency between freshly poured concrete and barbecue sauce, the array of life was astounding. The small creatures were all hyper-skittish: The mudskippers, crabs and other fauna would hastily dive into their burrows at our approach, although after some minutes of motionless waiting, legs and eyes and fins would begin to reappear. The mud would come to life again, and Harada would begin his fishing, casting and snagging the mudskippers through their gill covers in one smooth motion that did not alarm the creatures enough to send them headlong into their hidey-holes. We had to keep an eye on the time, as the six-meter tides of the bay rise very quickly. I spent three days out on the farther flats, with the incomplete dike always looming in the background.In December of 1997, I visited the bay again, and walked out to the areas where I had photographed and watched Harada. The gata had dried out and cracked deeply. The remains of small animals were scattered across what had been a galaxy of life. Nothing moved; the clicking, gurgling sounds of the crabs and the cries of gulls and terns were replaced by an occasional rustle of wind, nothing more. I photographed from what were -- as best I could estimate -- the same places I had done so the previous year. Some of the results are here on these pages. The government was absolute in its refusal to cancel this project, even in the face of growing opposition within Japan and from overseas. The World Wildlife Foundation and the Japan Wetlands Action Network joined with local fishermen in repeatedly petitioning the Japanese government to halt the construction of the dike. In 1998, Hirofumi Yamashita, a local anti-development activist who had worked and organized against the destruction of the bay's tidelands since 1972, was awarded the Goldman Environmental Prize for his untiring efforts. All this, however, was to no avail. The Ariake Sea is famous for its nori, the seaweed that is dried and pressed into dark sheets; it is perhaps best known as the outer wrapping of the rolled varieties of sushi. Until 2001, the Ariake Sea produced 40 percent of Japan's total nori harvest, which was worth about JPY40 billion per year. In 2001, the harvest in the four prefectures (Nagasaki, Saga, Fukuoka and Kumamoto) surrounding the Ariake Sea dropped by between 23 percent and 50 percent of the volume of the 2000 harvest. As a result, unit prices rose as much as 33 percent, but the overall quality was markedly poorer. This year has so far proved to be much worse and the nori producers of the Ariake -- most of whom, like Harada, combine nori aquaculture with commercial fishing for various species in their respective seasons -- face financial ruin. This aspect of the disaster has finally drawn the government's attention, and after much official hand-wringing, a compromise decision was made to open the two sluice gates near the ends of the dike to allow the waters of the bay into the area originally designated as the freshwater catchment reservoir. Initially, the gates will be opened for two months, but work will continue on a second interior dike and the landfill behind it. Last year Nagasaki University professor Hideyuki Nishinokubi, a specialist in fisheries engineering, completed a study of the effects of the dike's closure of the bay. He concludes that opening the gates would be far from sufficient to restore any semblance of the original flow. It is apparent that the strong tidal surges across the whole of the bay's flats flushed vast quantities of nutrients into the waters of the Ariake Sea, and that those nutrients were critical to the nori's growth.  A twice-daily tidal ebb and flow up to six meters sweeping across a seven-kilometer bay swarming with life could not conceivably be duplicated with the same tides directed through two small openings only a few dozen meters wide. Studying the effects of the flow through the gates may help assess the depth of the dike's disastrous impact but over the long run will really do nothing to lessen it.

A twice-daily tidal ebb and flow up to six meters sweeping across a seven-kilometer bay swarming with life could not conceivably be duplicated with the same tides directed through two small openings only a few dozen meters wide. Studying the effects of the flow through the gates may help assess the depth of the dike's disastrous impact but over the long run will really do nothing to lessen it.Moreover, other economic consequences are making themselves apparent. Tairagi (pen shell in English) is another species symbolic of the Ariake Sea, and since the closure of the dike, the number harvested has plummeted and catches of various species of fish off the Shimabara peninsula are dropping. It seems that the sacrificed tideland was a nursery for the young of various species and the smaller creatures that make up the base of the Ariake's food chain. The cosmetic compromise of opening the narrow gates for a limited period of time cannot restore the intricate mosaic of life in Isahaya Bay or the Ariake Sea as a whole. We are witnesses to the death of a wetland of vast importance. There is a lesson here, for those with vision wide enough to take it all in. What has happened -- and is continuing to happen -- in Isahaya Bay is not an isolated case. And while the destruction of an important part of Japan's remaining natural heritage is tragedy enough, it is just a symptom of a greater malady. That same cancerous sickness of short-sighted tribalization spreads throughout modern Japan's cultures of business and governance. Corporations and government organizations view their own "territory" as paramount in importance, all too often with disastrous results. Cases in point are the recent scandals of falsified safety data at nuclear power generating plants, the failure to implement measures to stop the ingress of mad-cow disease, fraudulent food-labeling ... the list is far too long to even briefly cover here. There is no long view, there is no realistic attempt to clearly see and address the challenges in front of this nation in this new century. The tragedy of Isahaya Bay is an example and a warning. Is it seen? Is it heard? The coming decades will tell. @ |

|

Note: The function "email this page" is currently not supported for this page.