(Figure 1: Plot Structure Before Subdivision) (Figure 1: Plot Structure Before Subdivision)

LAST MONTH, WE EXPLAINED how Japanese giant 'XYZ' had plans to move into a quiet residential area and shatter every-one's peace. Glenn Newman detailed his group's struggle to deal with the company's wily wielding of the red-tape gun. Now, we discovered who came out on top -- either the residents on the interests of big business.

Strike -- You're Out

Strike One: The City of Yokohama sent me a registered letter, within which they enclosed my original list of demands and a note informing me that the city was unable to accept the demand letter because it had been sent to the wrong department. Noticeably absent from the city's letter was any indication of where I should re-direct the letter to, or any invitation to do so. (Incidentally, refusing to accept an application over an extended period of time due to incompleteness or on some other formalistic pretext has been a tactic regularly used by Japanese bureaucrats to avoid a review of an application on the merits in difficult or politically sensitive cases. At one time this tactic was, in effect, judicially sanctioned by rulings which held that the failure to accept an application was not an administrative action and therefore could not constitute grounds for bringing suit against the governmental body which refused to accept the application.)

Strike Two: Not surprisingly, the US embassy expressed polite curiosity in the situation but no interest in taking any action.

Strike Three: The local police, once they got over their shock that anyone from the neighborhood, let alone a group of foreigners, would actually visit them to inquire about this matter, basically said that if City Hall was prepared to approve the project, then really there was nothing they could do: shikata ga nai.

An End-Run Around Yokohama's Zoning Rules

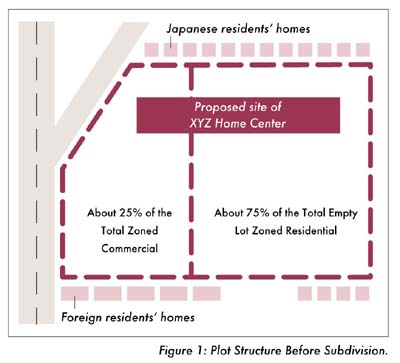

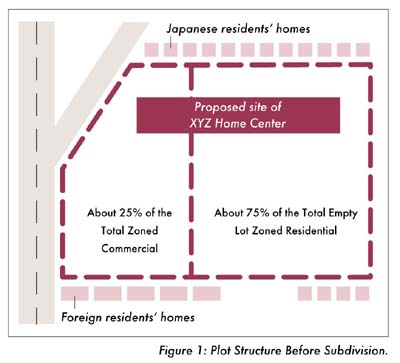

We were running out of options. But our resourceful landlord had another card up his sleeve: zoning violations. Interestingly, the planned site of the XYZ super-store was predominantly zoned for residential, not commercial, development. At first glance you would think that this fact would have given us a 'slam dunk' case for stopping this huge commercial development in its tracks. Not so.

Japanese law and Yokohama rules, at least as interpreted by the Yokohama city authorities, provide that if the greater part of a single plot of land is zoned for commercial use, then the entire plot can be used for commercial use.

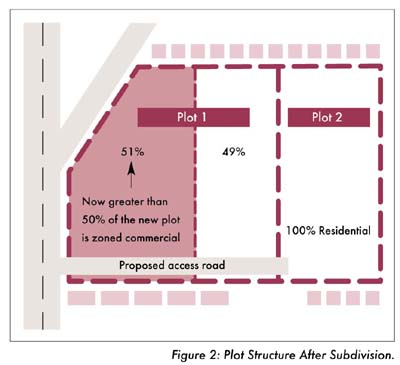

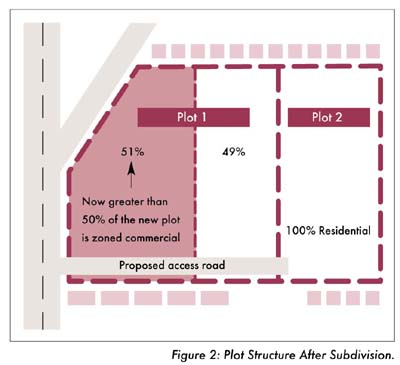

So what, you may ask, given that I have just said that the majority of this site was zoned for residential use? To understand why this rule is important, you need to know one more land use rule, or rather the absence of a rule. Generally speaking, there is no restriction on the right of an owner of a plot of land to freely subdivide its property, such as to divide one plot into two. So that's what XYZ did.

Subdividing the property into two separate plots did not change the zoning designations that applied to the site. Critically, however, the creation of two plots where there previously had been just one did change the relative percentages of commercially and residentially zoned property on each of the now two separate plots. Where previously there had been a single plot predominantly zoned for residential use, there were now two plots, one of which was zoned slightly more for commercial than residential use and the second of which was zoned exclusively for residential use. Based on this new configuration, XYZ was able to use all of Plot 1 (compare Fig. 1 and 2) for its store since a bare majority of that plot was zoned for commercial use. But XYZ was not satisfied with the use of just Plot 1. XYZ wanted to use the residentially zoned Plot 2 for its store as well. Impossible you say? Not at all.

XYZ submitted plans to the city to build a small four-flat apartment building in one corner of Plot 2. Each apartment would have a floor space of around 500 square feet or less. This four-flat building would be surrounded by 60 parking spaces. At one of our Sunday evening private meetings we asked XYZ the obvious question: weren't these 60 parking spaces really intended for XYZ's customers? XYZ replied that if the store's rooftop spaces filled up, then naturally customers would be free to use any of these spaces that weren't being used by the residents of the apartment building. And in an audacious display of fearlessness, XYZ volunteered that it had no immediate plans to actually break ground on the apartment building, but they would commence work on the parking spaces right away.

(Figure 2: Plot Structure After Subdivision)

(Figure 2: Plot Structure After Subdivision)

We argued with the Yokohama authorities that the city clearly intended for most of this site to be developed with residential housing in keeping with the residential character of the neighborhood, that XYZ was shamelessly exploiting a loophole in the zoning rules to defeat the city's clear intent when it zoned the site primarily for residential use, and that under these circumstances the city had an obligation to prevent this perversion of the rules and reject XYZ's request for a building permit. In other words, we were arguing that the city should look at substance over form. In response the Yokohama authorities expressed quiet admiration at XYZ's skillful use of the rules and said that regrettably there was nothing they could do: shikata ga nai.

Aside from the emphasis on form over substance, there was also a vague whiff of, shall I say, 'over-familiarity' between XYZ and the contractor, on the one hand, and the city officials, on the other, which was reflected in the officials' unwavering and unconditional support of the store and their perfunctory dismissal of the concerns of the residents.

I am not suggesting that brown paper bags stuffed with yen were passed to the officials to gain their acquiescence. However, the relationships between government officials and their counterparts in industry do tend to be rather cozy. Although there have been some moves to rein this in recently, especially at the national level, businessmen (and they are almost always men) still do entertain officials, sometimes extravagantly, in order to cultivate good relationships. The fact that government officials at all levels typically have early mandatory retirement ages also may tend to encourage them to see things from the point of view of the companies (and future employers) that come before them.

Any Other Recourse?

Having failed in all of our attempts to derail or significantly slow down the project, the city of Yokohama issued a building permit to XYZ. Did we have any other recourse? Yes...on paper.

One possible recourse was to initiate mediation under which the city would sponsor formal mediation between developers and residents that were unable to reach a consensus at the public meetings. On the surface, city-sponsored mediation seems tailor-made for this situation. Upon further examination, however, it was quickly apparent that mediation would be an empty exercise. First, under the rules mediation could not be commenced until after the building permit was issued. Second, the commencement of mediation would not stay construction. There is also no terminal date on the mediation. In other words, mediation can continue until the parties reach an understanding or until (or even after) construction of the store is finished. Third, mediation is only mediation. It has no binding effect. In Yokohama, it is also not burdened by an assertive or active mediator. Although city officials are supposed to bring the sides closer together, in practice the mediators tend to be fairly passive. The mediation sessions thus end up as little more than retreads of the public meetings that had already failed to achieve a consensus in the first place.

Another possible recourse was to seek administrative review of the city buildings department's decision to grant the building permit. This is theoretically possible, although, as with administrative agencies everywhere, bureaucrats are loath to second-guess the decisions of their colleagues. Such deference may be even more manifest in Japan for several reasons. Important decisions in Japan tend to be reached by consensus. This means that it is very possible that the bureaucrat reviewing a decision nominally made by another department or section may actually have been aware of, and even assented to, that decision in the first instance.

In addition, it may be a clichEbut Japanese do tend to be more concerned about 'face' than Americans. This makes it less likely that an agency would find that a decision by someone within the agency was in error because such an admission would reflect badly both on that individual and the reputation of the agency as a whole.

It was also unclear whether our landlord even had standing to seek administrative review since Yokohama's zoning rules were arguably intended only to protect residents. Owners not in residence who lost property value due to the misapplication of zoning rules were apparently considered outside the intended zone of interest of the zoning rules, or so the city contended. In any case, the commencement of administrative review would not lead to a suspension of construction in the vast majority of cases, making it of little practical value.

The last possible recourse was to seek judicial review of the city's decision to grant a building permit to XYZ. This also proved unworkable for a variety of reasons. First, civil litigation rules tend to make it more cumbersome to bring actions against governmental entities. Courts also tend to defer to the decisions of local authorities. This may not be much different from the principles governing judicial review of administrative decisions in the US, at least in the abstract. In this case, however, this also meant that the court was unlikely to take up the zoning issue in a serious way even though the city's application of the zoning rules in this case was, at least in the opinion of my landlord/lawyer, highly questionable.

Second, as noted above, the landlord's standing to even bring a case was seriously in doubt.

Third, obtaining the equivalent of a preliminary injunction in Japan in a timely manner is nearly impossible. It is not unusual for a court to hold hearings on a motion for a preliminary injunction for six months or even a year before ruling. With an accelerated construction schedule of around three months, clearly an injunction was not a viable option, even if my landlord had been willing to post the massive bond required by the court as a condition to the grant of an injunction.

Fourth, damage awards tend to be very small in Japan. Even were our landlord to prevail, his recovery would likely be relatively small and he would not be entitled to recoup outside attorneys' fees. Punitive damages also are not available in Japan.

Fifth, lawyers are few and far between in Japan and contingent fees are not permitted, even assuming the potential damage recovery were high enough to attract a lawyer in the first place. Our landlord happened to be a lawyer and was relatively active, both physically and mentally, but he was still over 80 years old and was not prepared to spend his remaining years tied up with this case.

Incidentally, Japanese often assert, with pride, that the reason litigation is so rare in Japan as compared to the US is that Japanese abhor open confrontation and prefer to resolve disputes privately. There is surely a lot of truth to this statement. However, as with the alleged (and rapidly evaporating) Japanese preference for small mom and pop shops, the Japanese government does not leave such an important issue to chance. Government policy imposes strict limits on the number of new attorneys (bengoshi) permitted to enter the practice of law each year.

When the writing on the wall was clear, my family and I moved to another house about a mile from where we were living. Most of the other foreigners followed suit in short order. My Japanese neighbors, who owned their homes, were not so fortunate. We, on the other hand, were all delighted with XYZ, a large, modern, clean store that sold a wide variety of quality merchandise at low prices. And did I mention that the store had great parking?

Lessons Learned

That's the end of the story. I would like to suggest that this case represents a reasonably good, albeit obviously partial, microcosm of the Japanese approach to the regulation of business. Hopefully without taking too much liberty with the facts, I think the XYZ case illustrates the following, sometimes overlapping, aspects of the Japanese regulatory system.

1 Japanese regulations and the attitudes of Japanese government officials are still generally geared toward the protection of status quo business interests at the expense of new entrants (whether foreign or Japanese), consumers and residents. This is a generalization and the notion of a 'Japan Inc.' has so many cracks now that it may no longer even be a worthwhile metaphor. The restrictions, both legal and cultural, to foreign retail stores, for example, truly seem to be mostly a thing of the past, with large stores like Costco, Toys 'R Us, Eddie Bauer and others spreading (metastasizing?) all over Japan. Nevertheless, the observation that many Japanese government officials tend to see the 'care and feeding' of existing business concerns (such as the developer in the XYZ case) as their primary mission still has validity.

2Japanese tend to prefer private methods of resolving issues and disputes and will try to resort to those methods even when more formal or systematic mechanisms have been established by law or regulation. XYZ's ultimately successful efforts to build an informal understanding with the chairman of the neighborhood association and the neighbors for the construction of the store before beginning the formal notice and consultation process is one example of this inclination. Another is the series of private meetings held between XYZ's representatives and me and my foreign neighbors. Yet another may be the non-transparent building permit process itself, which may have been greased by the construction company's carefully cultivated, long-term and personal relationships with officials in Yokohama's department of buildings.

3 The Japanese government still does not readily embrace the concept of deregulation.

An example in the XYZ case was the government's repeal of the Large Scale Retail Store Law (LSRSL) only to replace it immediately with another law which arguably invited local governments to re-regulate large stores to fill any vacuum left by the diminution of the national government's role in this area. Indeed, Japanese does not even have a word for 'deregulation.' The Japanese term often translated into English as 'deregulation,' kisei kanwa, literally means the 'easing of regulation;' clearly not the same thing as the removal of regulation.

4The importance, and limitations, of foreign pressure -- or gaiatsu -- on the evolution of Japanese regulation of business. As noted above in connection with the LSRSL, the Japanese government is often more willing, or finds it more convenient, to ease its regulations as a result of gaiatsu, than lobbying by domestic interests. In many instances there is also a large Japanese constituency in favor of the easing of regulations in a particular industry but it is more convenient or comfortable for all concerned to blame the Office of the United States Trade Representative or some other foreign element for a change in a law that may adversely impact one Japanese constituency (such as mom and pop shop owners) even if a much larger group (such as Japanese consumers) is benefited by the change. As noted above, however, there is also sometimes less to the deregulation than meets the eye. And obviously the US government is understandably not willing to waste its chits on lost causes (witness my failure to attract the US embassy's interest in XYZ's building plans).

5The tendency of Japanese officials to elevate form over substance. This was seen in the position taken by the Yokohama officials toward XYZ's use, or misuse, of the zoning and land use regulations. It was also seen in the city's formal rejection of my demand letter due to its being 'misaddressed.' The latter was clearly also a tactic to try to avoid or delay further contact with a group of rabble-rousing foreigners. However, the fact that the city officials even used this tactic reflects a 'form over substance' mindset that the sender expected would be shared by the recipient.

6 A narrower understanding of the meaning of 'consensus' in Japan than may be commonly understood by Americans. Japan is regularly described as a 'consensus-oriented' society that emphasizes 'harmony' over other values, such as the rights of individuals. There is a lot of cultural truth to this statement. But, in my opinion anyway, there are at least two important caveats.

First, the desirability of 'consensus' typically only refers to consensus within a defined group. For example, it was important for the members of the neighborhood association to reach an internal consensus as to how to respond to XYZ and what demands to ask the association chairman to make of XYZ. It was not important to them that the changes to the XYZ store that they requested were diametrically opposed to the interests of their foreign neighbors. Our Japanese neighbors were indifferent, or at least oblivious, to the concerns of the outsiders among them.

Second, Japan's consensus-oriented society sometimes may mask a less attractive truth -- that those with power or money tend to get what they want and, without any realistic legal or other recourse, there's little ordinary people can do about it. The fact that those with power or money tend to get what they want is a staple of the human condition and is by no means unique to Japan, which actually has a more egalitarian society than most. What may be somewhat different is the greater willingness of Japanese to accept their powerlessness with relative passivity, with the common refrain: shikata ga nai.

In this context, 'consensus' does not necessarily reflect a negotiated outcome accepted by all constituencies to a particular course of action but rather a fatalistic resignation by some that they have little ability to affect the outcome and it is futile to even try. (There are of course exceptions to submissiveness to authority, such as the multi-decade fight by a coalition of farmers and leftists against the Narita Airport outside Tokyo.)

7 Overly cozy (though usually not outright corrupt) relationships between Japanese regulators and those they regulate still seem to permeate the scene. I have saved this lesson for last because I want to distinguish it from the policy bias in favor of status quo business interests noted earlier and also because I do not want to overemphasize its importance. Japan is not Indonesia. Japan is not even Chicago, where I grew up. Most Japanese officials are diligent, hardworking and honest. Nevertheless, the continued reliance on informal ties and personal relationships can lead to bias, consciously or unconsciously, against parties which are outside the circle. In the XYZ case, the apparently cozy relationship between the Yokohama city officials and XYZ and its contractor was arguably observable in the officials' unblinking acceptance of XYZ's positions over the views of residents, including some Japanese residents.

The possibility that some of the city officials may have had some prospect of post-retirement employment with this or some other developer or general contractor may also have affected their stance toward XYZ. In fact, at the highest levels of the national bureaucracy, there is a term -- amakudari (literally 'descent from heaven') -- for the practice of a government official retiring to a cushy job in the industry he formerly regulated. The danger that the amakudari system can lead to corruption or unconscious bias by regulators focused more on their next job than their current one is well-known and often discussed in Japan. Officials in the city of Yokohama's department of buildings certainly do not have the same exalted status as the mandarins in the top ministries in Tokyo. Nonetheless, they may have a similar motivation to avoid ruffling the feathers of potential future employers.

In a different way, the relationship between the developer and the Buddhist priest/neighborhood association chairman, possibly greased by contributions for temple upkeep or the like, may have led the chairman to accept the 'inevitability' of the store more readily than might otherwise have been the case.

In the End...

Anyone giving a speech about the regulation of business in the United States would surely have their own list of abuses and deficiencies, some of which may be quite similar to the items mentioned in this speech, though probably with a different spin or emphasis (such as the revolving door between government and industry and its impact on the impartiality of regulators). My point is not to trash the Japanese system or to contend that the Japanese system is somehow unique (or uniquely deficient) when compared to the regulatory regimes of other countries, only to try to explain some aspects of it.

Lastly, I am certainly not saying that it is hopeless to try to get anything done in Japan. I've been involved in or observed many cases where foreign companies have been able to effectively navigate the Japanese regulatory system. To do so, however, clearly a lot more firepower and patience is required than my neighbors, my landlord and I possessed in this case. @

Glenn Newman is an associate general counsel with Cadence Design Systems in Portland, Oregon. His article previously appeared in the Oregon Review of International Law.

|

(Figure 1: Plot Structure Before Subdivision)

(Figure 1: Plot Structure Before Subdivision)

(Figure 2: Plot Structure After Subdivision)

(Figure 2: Plot Structure After Subdivision)