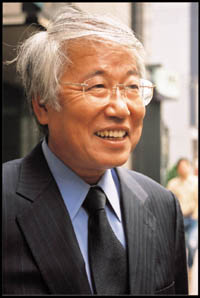

Man with an Edge

Back to Contents of Issue: July 2002

|

|

|

|

by Henry Scott-Stokes |

|

INTERNET INITIATIVE JAPAN (IIJ), a telecom industry trailblazer since the early 1990s, confirms my belief that the little fellas stand a chance against the big guys in Japan, even when the big guy in this case is the monolithic NTT. INTERNET INITIATIVE JAPAN (IIJ), a telecom industry trailblazer since the early 1990s, confirms my belief that the little fellas stand a chance against the big guys in Japan, even when the big guy in this case is the monolithic NTT.Everything depends on leadership. Koichi Suzuki, 55, is the man who made IIJ, starting from scratch and running uphill. I attribute his success to the man's charm, his passion and his will to succeed, plus his ability to attract some 500 engineers and keep them in place. "NTT is big," Suzuki said during a recent chat. "But even so, they can be very quick." He does not underestimate the colossus. NTT was formally split up a decade ago but functions still as a sprawling group with tentacles all over. But Suzuki has held up admirably against NTT. He took risks. At the very outset, he had to pledge family assets to get the bank financing he needed. His company is still small, i.e. vulnerable. Today -- after an eight-year spell during which IIJ increased sales at a compound 67 percent per year -- the company boasts sales of only slightly over $300 million a year compared with NTT's $92 billion last year. The latter has 200,000 on its payroll compared with a grand total of 1,000 at IIJ group companies. NTT includes that formidable entity NTT DoCoMo, the mobile arm of the group, and NTT Communications -- IIJ's direct competitor. NTT has a global reach through DoCoMo, whereas all IIJ's customers are Japanese. Finally, NTT has a phalanx of old boys in parliament working as a pressure group. Suzuki waves his arms indignantly when I ask him whether he meets politicians from time to time. "No!" he says. Starting a year ago, he has done public service as a member of a telecom industry advisory board that reports to prime minister Junichiro Koizumi. But the role does not suit him all that well, some say. An outspoken member of the committee, Suzuki has found to his chagrin that his views are not always noted by the officials responsible. What he cares about is IIJ. The company is his creation. Yet how precisely he came to take over as shacho is a bit unclear. One version of events, as told to me by him, is that he was one of a group of friends, mainly academics, who were fascinated by the potential of the Internet in the early 1990s. The others took the lead and invited him to join with them in setting up a company, saying that they had the money to do it. They cajoled him into the parlor. But when the moment came, there was "no money," Suzuki recalls. He had a little and took charge. Another version of events I have heard from his staff is that Suzuki stepped to the fore as the chief person to negotiate with the Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications on behalf of the fledgling IIJ to get a license to run an Internet service provider. The man has charm. He was no doubt an ideal person to negotiate with the ministry officials. Not that the job was easy. So far as I have gathered, getting the license was a traumatic experience for Suzuki. The negotiations dragged on. But then, at a critical moment -- after about a year -- the license came through. IIJ was in business. I wonder whether there were many people at the time -- this was 1992 -- who thought that Suzuki would succeed. He was brilliant, a self-taught techie. But he had little real experience as a hands-on entrepreneur. He also had relatively little money. You need billions of dollars in telecoms. How could Suzuki hold a candle to NTT, KDDI and others? He brought in two trading companies as shareholders in IIJ -- Sumitomo and Itochu. But they were not active in management; they are just shareholders and Suzuki outranks them with a personal holding of 10 percent of the company. Ten years later, I am happy to report, Suzuki is still there. He has fabulous technology. His staff says he services mainly "top-end" companies -- that means big firms. He calls on IIJ for the Internet, on a fast-growing affiliate called Crosswave Communications for data communications, and on other companies in the group for related services.  Suzuki has some support among prominent analysts in Tokyo, including Hiroshi Yamashina at Goldman Sachs, an expert on Internet companies, and Kentaro Kimura, a tech analyst at Credit Suisse First Boston. Let me cite a CSFB publication of Feb. 28 to give an idea of what these houses see in the IIJ group: "An era in which Internet Initiative Japan can fully exhibit its foresight and technological prowess is drawing closer" is the heading on that recent publication. It carries a 'buy' recommendation for the stock.

Suzuki has some support among prominent analysts in Tokyo, including Hiroshi Yamashina at Goldman Sachs, an expert on Internet companies, and Kentaro Kimura, a tech analyst at Credit Suisse First Boston. Let me cite a CSFB publication of Feb. 28 to give an idea of what these houses see in the IIJ group: "An era in which Internet Initiative Japan can fully exhibit its foresight and technological prowess is drawing closer" is the heading on that recent publication. It carries a 'buy' recommendation for the stock.Suzuki has become a center of attention. On one recent afternoon, when I was visiting IIJ's head office at Takebashi in downtown Tokyo, I learned that some 60 analysts had turned up that morning for a 'results meeting' for the year to March 2002. Suzuki advised the assembled throng -- apparently they were the largest group of analysts ever to gather at IIJ for such an occasion -- that an important development is afoot in telecoms in Japan. This requires explanation. For years the prices that telecom companies in Japan could get for their IP services were going down. To be specific: the "average revenue per 1 Mbps" in early l997 was JPY2 million, according to IIJ. By early 2002 that return had been squeezed all the way down to JPY200,000. Some experts maintain that this was the effect of NTT and KDDI dumping their services. Whatever the cause, the outcome was drastic for IIJ -- it depressed earnings. Suzuki says, however, that the long-term decline in average revenues per 1Mbps is in the course of being reversed or at least halted. He didn't say that to me, he said it to the analysts. But one of his staff, who was present at the meeting, repeated the gist. This was Junko Higasa. She serves as Suzuki's IR/PR representative. (Let me draw attention to the fact that Suzuki-san is one of the rare shacho in Tokyo today to entrust these duties to a woman. It is an indication that he is a man who chooses to do things differently.) Be that as it may, his remarks apparently stirred the analysts. I can see why. They have been issuing reports -- now buttressed by Suzuki's comments -- that carry spreadsheets with numbers running through 2006, showing that IIJ is on the verge of a tremendous improvement in its performance. Net income, says a Goldman Sachs report dated May 23, should improve from this year's mixed result (the good news was that IIJ recorded its first operating profit in three years; the bad news was a record loss of JPY7.4 billion on revenues of JPY39.9 billion, caused by the need for IIJ to consolidate part of Crosswave's losses). By 2007, according to that cheerful Goldman Sachs report, IIJ revenues should have surged to JPY95.1 billion, and net profits should hit a whacking JPY10.5 billion. Wow! Not everyone is impressed. "Ah, spreadsheets are wonderful things," said Ben Wedmore, an analyst at HSBC Securities. Such skepticism may be called for. But on the other hand, long-term forecasts by major investment houses are based on judgements about ongoing technology, not just on rosy assumptions. Not that the latest results can be brushed aside. These came out in late May, both for IIJ and for its affiliate Crosswave. By any standards, the numbers made salutary reading. They are not the stuff of 'buy' recommendations. Take Crosswave Communications. This key affiliate, which has built up an optical fiber system all over Japan in four years, recorded a deficit of over JPY13 billion in its latest full year as compared with sales of JPY10 billion. No matter how one considers these numbers, they imply risk. Little Crosswave -- the company is listed on Nasdaq in the US, as is IIJ -- is burning through its cash. "Cash and cash equivalents," the last line in the company's accounts, plummeted from JPY24 billion on March 31, 2001, to JPY8.6 billion a year later. What is Suzuki doing about this? He has concluded a syndicated loan agreement with four Japanese banks, announced on May 21. Here is an excerpt from the joint Crosswave/IIJ announcement of the deal with Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corp., UFJ Bank, Sumitomo Trust & Banking and Mizuho Corporate Bank: "The arrangement consists of a six-year long-term loan of up to JPY15 billion, and a short-term line of credit of up to JPY5 billion... The loan... is secured by substantially all of Crosswave's assets... IIJ has agreed to provide cash deficiency support for the period of the loan facility... IIJ deposits JPY5 billion with an agent bank." I checked IIJ's accounts to see how much cash the company had in hand at the end of the last business term -- the amount was JPY11 billion at March 31, 2002. In other words, half of its cash in hand -- a little under -- is needed for what is called "cash deficiency support." This is not a term of art I have come across before. It's worrying. Yet I have to say this -- morale at IIJ is high. I visited the company twice after the results came out. People take great pride in the fact that IIJ declared an operating profit in the year to March 2002 -- for the first time since the company did its IPO in l999. They also note that revenues more than tripled at Crosswave in its latest year, indicating that the company is in a flat-out expansion. They were saying that it was splendid how four Japanese banks had agreed to lend money to a small firm that recorded such a loss. This is not simple-minded optimism, as I see it. Japanese banks have been cutting down their loan portfolios very sharply for years. Their willingness to lend to Crosswave is impressive. I imagine that one reason the four banks were ready to help was that Crosswave has powerful shareholders. The biggest shareholder in terms of stocks held is IIJ. The company owns 38 percent of Crosswave. The next two shareholders are Toyota Motor and Sony, each with 23 percent. I got interested in this. I asked Suzuki how he persuaded these two mighty corporations to join in, when he set up Crosswave -- in October l998 -- with IIJ taking 40 percent of the stock, and the other two accepting 30 percent each. Suzuki explained that he knows Nobuyuki Idei, the chairman of Sony, and also, if slightly less well, Hiroshi Okuda, chairman of Toyota, and some of the senior Toyota people working with him. He wrote a detailed proposal and submitted it to the top brass of Sony and Toyota. Back they came with an OK. Idei and Okuda are laymen in telecoms, and they trust Suzuki. I started this article by saying that Suzuki has managed to run rings around NTT, and that this was a sign of where the Japanese economy is going -- startups and small firms are the salt of the earth. Of course, this is true. Mr. Suzuki is like so many of his contemporaries in business in this country in the small or startup sector. He is a one-off, an original. As such -- like the rest of us -- he sometimes makes mistakes. With the benefit of hindsight, I believe, he should have listed his two main companies -- IIJ and Crosswave -- in Tokyo, not in New York. The stocks have been neglected in the US, because no one there has heard of either firm. What J.P. Morgan, Goldman Sachs, CFSB and others are saying is that, this way, the stocks of the two companies have come to be undervalued -- at a heavy discount from their issue prices. Crosswave has been limping along at just above the $1 line, at which Nasdaq delists a firm under certain circumstances. Would you consider joining Toyota and Sony as a shareholder in this company at $1 a share? If not, then what about IIJ? A year ago, a British company, Cable & Wireless, tried to buy IIJ, according to widespread rumors at the time. It's no wonder that the UK firm was interested. But Suzuki -- he would not comment -- is not a seller, I believe. If you have built up a company in Japan, it is yours for keeps. @ Henry Scott-Stokes has been reporting and writing about Japan since the 1960s. He wrote Success in Small Packages for the April 2002 issue of J@pan Inc. |

|

Note: The function "email this page" is currently not supported for this page.