Pediatric Predicaments

Back to Contents of Issue: March 2002

|

by Willam Hall |

|

|

EARLY JANUARY BROUGHT THE the annual media review of government estimates of the number of births, deaths, marriages and divorces for the previous year. In 2001, the estimated number of births fell yet again, to a new record low of 1,175,000 babies. We will have to wait until 2002 to see whether the pundits' belief in the 'halo effect' of the birth of Princess Masako's first child on December 1, 2001 will in fact lead to an increase in births. There was certainly no impact in 2001, despite the fact that the number of marriages increased to over 800,000 for the first time in 24 years.

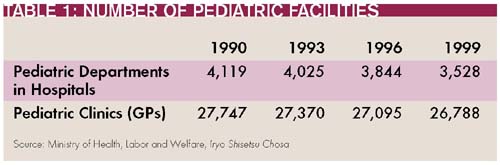

A little remarked-upon phenomenon accompanying the declining birthrate has been the decline in the number of pediatric facilities in Japan. This is a topic of considerable importance, since baby doctors have increasingly become new mothers' first port of call for advice in a society where the role of the extended family in child raising has diminished significantly. Pediatric Facility Closures According to the Iryo Shisetsu Chosa (Census on Medical Facilities) published by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, the number of pediatric departments in hospitals has declined by almost 600 between 1990 and 1999 (See Table 1). Some of this loss can be attributed to hospital closures, but not entirely so, since the percentage of hospitals having a pediatrics department also declined, from 46 percent in 1990 to 43 percent in 1999. Thus, we see a decline in both absolute and relative terms. By way of contrast, the number of psychiatry departments increased in both absolute and relative terms from 1990 to 1999, indicating the increasing awareness and recognition of mental health problems in Japan.

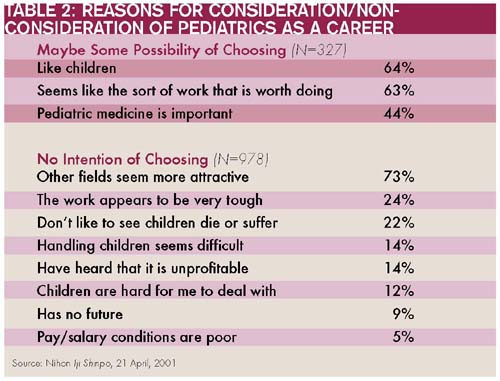

Almost 1,000 pediatric clinics (GPs) were also closed in the same period, with the ratio of pediatric clinics to total clinics falling from 34 percent to 29 percent between 1990 and 1999. Although the absolute number of GP pediatricians in Table 1 may appear large, it should also be remembered that the average age of a GP in Japan is now almost 60 years, meaning that continued reductions in the number of pediatric GP clinics can be anticipated. Medical Student Perceptions of Pediatrics A study published in the April 21, 2001 edition of the weekly Nihon Iji Shinpo (Japan Medical Journal) provides an interesting perspective on some of the reasons for this reduction in pediatric facilities. The study was carried in an article entitled Shoni Kyukyu Iryo ni Okeru Shonika-i Fusoku (The Shortage of Pediatricians in Pediatric Emergency Care) and was co-written by Drs. Tetsuro Tanaka, Kotaro Ichikawa and Yoshiyasu Yamada. The authors interviewed sixth year medical students at universities with medical departments. The study was conducted in September 2000, with the timing deliberately chosen to be about six months before graduation. 23 medical schools were selected by random sampling from among the 80 medical schools nationwide in Japan, and the students were requested to anonymously fill in a questionnaire. 1,316 responses were received; 69 percent from males and 31 percent from females. 75 percent of the sample was age 25 or less, with a further 14 percent age 26 to 27. In 2000, some 7,538 students sat for the national medical exam, and thus, with a randomly selected base of slightly less than 20 percent of total final year medical students, the study can be considered as representative. Students were asked whether they had decided on which department they planned to enter after graduation. 82 percent had decided by this stage. Of these, 9.5 percent had decided to enter the pediatric field (8 percent of males and 12 percent of females). The students were then asked whether there was any possibility in the future that they might choose to enter the pediatric field. 25 percent said there might be some possibility, 74 percent responded that there was no possibility, while 1 percent were undecided. Among the reasons given for this choice, the positive responses to the question appear rather idealistic in nature, while the negative responses are much more hard-nosed. (See Table 2) Profitability Issues Impacting Pediatric Facilities Among the negatives is the perceived lack of profitability and poor pay conditions in the pediatric field. In Japan, the great majority of hospitals are currently running in the red. Further, because of the way the national health scheme is structured, hospitals and clinics tend to make a significant percentage of their profits from prescription drugs. Small children, however, are unable to take a large number of drugs at any one time, and also do not usually have life-threatening diseases requiring expensive drugs. Thus, the profitability per patient from drugs is significantly lower than with adults. And with a decreasing number of babies, vacant beds in hospital pediatric wards offer an opportunity for improved hospital profitability if they are transferred to different departments.

Overworked Pediatricians Another negative identified in the student data is the tough working conditions of a pediatrician. The reduced numbers of available pediatric emergency care sections are being flooded with young parents bringing their child along for problems that, for the most part, are minor in nature. The November 8, 2001 edition of the Asahi Shimbun reported the case of Nerima Ward in Tokyo which opened an emergency pediatric clinic on weekday evenings and holidays, and had GPs from the surrounding area work in the clinic on a rotation basis. In the four months after the opening of the emergency care clinic 1,629 patients were seen, and of these only five required additional testing or admission to a hospital. One reason for opening the clinic was to relieve the pressure on the major hospital in the district at which the handling of emergency pediatric care was concentrated. Pediatricians there were severely overworked, and getting virtually no sleep for days on end. However, the expected decrease in the number of cases treated at the major hospital did not occur; the addition of the clinic simply created extra demand. Anxious Mothers The reasons for this overuse of emergency pediatric care are manifold, but are rooted in the sociocultural changes occurring in Japan. Due to the increasing nuclearization of Japanese households, the reduced numbers of children being born, and the breakdown in community involvement in major cities, young mothers frequently do not have anyone nearby who is experienced in raising children and to whom they can turn to for advice when their child becomes sick. Furthermore, young mothers in Japan receive little or no training about what to do if their child gets a fever or starts vomiting. With the birthrate at around 1.1 in major cities such as Tokyo, the first child is increasingly the only child, and young mothers often lack confidence in their ability to take an appropriate course of action when their child becomes sick. Thus, the instinctive reaction tends to be to take the child off to the (emergency) pediatric facility, just to be on the safe side. As one doctor stated, "Young mothers think of pediatric facilities as being just like convenience stores, where they can come along for the slightest need." This 'convenience-store' mentality towards emergency pediatric care has become so widespread that, in Gunma Prefecture, hospitals on standby to offer 24-hour emergency pediatric care are rotated, but information on which hospital is on rotation on any particular day is made known only to the ambulance and the hospitals themselves. A spokesman for the prefectural authorities stated that if the information was made public, the hospital would be overrun with minor cases and would not be able to perform its proper emergency functions. A group in Kyoto called 'Office Power-Up' recently published a study among 300 young mothers on what they most wanted in regard to pediatrics. The main information desired was word-of-mouth recommendation on good pediatric GPs and which hospitals are open on evenings and holidays for emergency care. According to a spokesperson for the group, the mothers also desire to have a doctor who can sympathize with their anxiety. "If the doctor has an attitude of 'why did you bring the child here with such a trivial illness,' this will further reinforce the lack of confidence that a young mother already feels about her child-raising ability." Some Implications Faced with the most rapidly aging society in the world, the declining birthrate will further compound the already heavy debt-to-GDP ratio facing Japan. Barring the unlikely acceptance of immigration or the free movement of labor into Japan (see Japan Studies, June 2001), Japan faces a future of an increasing number of pensioners and too few workers to support them. For this reason, increasing the birthrate has become a major political issue. With over 50 percent of women in the workforce, the Japanese government has identified the insufficient number and quality of daycare centers as a major factor affecting working women's desire to have children. Female pediatricians also face the same issue, and many have to take time off from their practice to care for their child, further exacerbating the shortage of pediatricians. Is there a business opportunity here for hospitals to go into the daycare business? They could provide peace of mind to young working mothers, with immediate access to medical care if necessary. The average age at first marriage for a Japanese female is now 28 years, and over 50 percent of women in their late 20s have never been married. Those who do marry are postponing the length of time before they have their first child. As word of the reduced availability of pediatric facilities spreads in the media, this may become an additional deterrent to having children. So, we can probably expect policy changes forthcoming that are designed to promote and improve pediatric services. Finally, it is clear that there should be a significant business opportunity, Internet-based or otherwise, in providing young mothers with explanatory information on medical care for children in an easy-to-understand form. @ William Hall (williamh@isisresearch-jp.com) is president of Isis Research Japan Ltd., which provides market research and consulting services in Tokyo. |

|

Note: The function "email this page" is currently not supported for this page.