Limping Towards China

Back to Contents of Issue: March 2002

|

|

|

|

by Sumie Kawakami |

|

HUNDREDS OF JAPANESE ENGINEERS have traveled the same path as Tanaka, crossing the South China Sea and looking for riches -- or at least a steady-paying job -- in China, South Korea and elsewhere. As Japanese manufacturers of all sizes aggressively restructure and cut production, many Japanese are giving up on their homeland to look for opportunity in one of the rising stars of Asia. Yet, as Tanaka has found out, success is hard to come by. The Japanese molding industry has been suffering lately because of reduced production of electronics products, as well as a continued exodus of Japanese factories to Thailand and mainland China, where production costs are significantly cheaper. Tanaka, who speaks very little Chinese, says life in China hasn't been easy. He used to manage 150 factory workers, which was no easy task, but he says the standard nowadays for Japanese factory managers in China is to handle up to 200 workers. "Now most factories are cutting costs, and you can guess what they cut first: managers," Tanaka says. "If you cannot manage (at least) 150 people you cannot earn your salary." HUNDREDS OF JAPANESE ENGINEERS have traveled the same path as Tanaka, crossing the South China Sea and looking for riches -- or at least a steady-paying job -- in China, South Korea and elsewhere. As Japanese manufacturers of all sizes aggressively restructure and cut production, many Japanese are giving up on their homeland to look for opportunity in one of the rising stars of Asia. Yet, as Tanaka has found out, success is hard to come by. The Japanese molding industry has been suffering lately because of reduced production of electronics products, as well as a continued exodus of Japanese factories to Thailand and mainland China, where production costs are significantly cheaper. Tanaka, who speaks very little Chinese, says life in China hasn't been easy. He used to manage 150 factory workers, which was no easy task, but he says the standard nowadays for Japanese factory managers in China is to handle up to 200 workers. "Now most factories are cutting costs, and you can guess what they cut first: managers," Tanaka says. "If you cannot manage (at least) 150 people you cannot earn your salary."

Industry sources say there are over 130 Japanese factories in the city of Shenzhen alone, out of which about 60 are related to molding. Headquartered in Japan, these firms normally send managers from Japan to supervise the production process. Tanaka was making HK$30,000, or a little more than JPY500,000, a month and sending a large chunk of that home to his family in Japan. When Tanaka's company collapsed in December, it sent him a fixed-date round trip ticket and nothing more. But after a disappointing job search in Japan the previous summer, Tanaka was in no hurry to return. Instead, he began applying for jobs via the Internet; as of mid-January he had one inquiry from a company in China. Tanaka and others like him are eligible for Japanese unemployment insurance, but they have to be in Japan at least a few days a month to receive the benefits. Tanaka says he plans to go back and forth between Japan and China for a while to collect his benefits and look for work. He says he doesn't want to stay in China forever. "I am assuring my family that Japan's economy will pick up within a year or two, so I can come back to Japan to be with them," he says. "I hope I'm right." There are many other Japanese manager-class engineers like Tanaka, according to Yukitada Ibaraki, another injection molding engineer working for Japanese molding company Taipan in Shenzhen. "As the employment situation worsens in Japan, many are willing to come here before they actually get fired," he says. According to Ibaraki, there are three types of positions available for manager-class Japanese engineers in Guangdong province. The top of the pyramid consists of those who are hired inside Japan and sent to the factory by the head office. Engineers hired by their Hong Kong branches are next, while those hired locally in China -- either by Japanese, Chinese or Taiwanese companies -- are on the bottom.

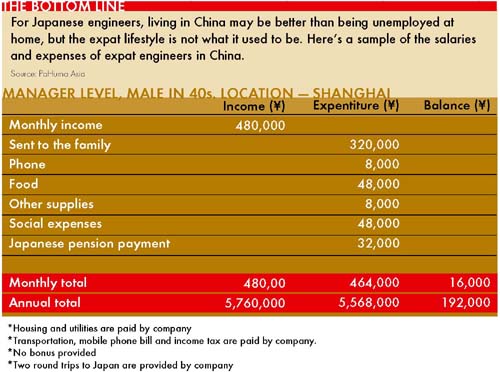

Manager-class engineers, those who belong to the first group, could make over HK$30,000 per month with full expat benefits, such as several trips a year back to Japan and other perks similar to their fellow managers in Japan. The second group receives between HK$25,000 and HK$30,000, and the third group gets less and very limited benefits. Some managers bring their families with them, but many live alone in China. In general, Japan-hired managers are much better off than local hires, Ibaraki says. Higher technology, lower cost The exodus of Japanese engineers is not limited to the molding industry. Tomoko Hata, marketing director of headhunting agency PaHuma Asia Group, says, "More and more people have been making inquiries about jobs in Asia since last summer," when electronics giants, including Matsushita and Toshiba, started announcing huge restructuring plans. At the same time, job offers for engineers in Asia are on the rise, she says. While the hollowing out in Japan has reduced engineering jobs drastically, Japanese companies are opening new factories overseas and looking for workers to run them. "The job market is interesting," Hata says. "Whenever a Japanese company announces a plan to launch new operations in Asia -- mostly in China -- that company needs staff to fill that role," Hata says. Headquartered in Hong Kong, PaHuma Asia has branches in Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan and China. The company specializes in finding employees for Japanese companies; as much as 80 percent of the job offers it handles are from Japan-based operations. The percentage of jobs it places for Japanese companies in China is even higher. In Shanghai, for example, about 90 percent of the jobs it fills are for Japanese companies. PaHuma Asia held a seminar in Tokyo in late October, specifically targeting middle-aged Japanese engineers seeking jobs in Asia. Out of over 100 attendants, about half were 50 or older, and 60 percent were unemployed, including those who accepted early retirement plans, according to the company. Companies throughout Asia are often happy to pick up these Japanese engineers, especially if the person has had experience working with high-end technologies. Part of the demand for Japanese engineers comes from companies in countries eager to catch up with Japan. Anyone with experience in such areas as liquid crystal displays, thin film transistors and, more recently, plasma display panels (PDPs) and organic electroluminescent (EL) technology ranks high with Korean companies, industry sources say. "I know at least three leading (Japanese) high-end panel engineers with electronics giants who were hired by Korean competitors" in 2001, says Satoshi Ohmori, an analyst at Mizuho Securities who watches the PDP market. Japan is still leading the globe in PDP technologies, after Fujitsu first developed its 21-inch full color PDPs in 1992. That success comes with a heavy price: Japanese companies first started dedicating research and development budgets to PDP-related projects back in the 1960s. But now, LG Electronics and Samsung of South Korea are catching up. Last year, LG started to export PDPs, and Samsung established a mass production system for PDPs, organic ELs and rechargeable batteries, which are all emerging as new core products to replace cathode ray tubes. As Korean exports rose, Japanese manufacturers got rid of some of their key engineers because they could no longer justify the accumulated R&D costs. And those engineers were often offered jobs by Korean competitors keen to close the gap with Japan even further, Ohmori says. Although there are very few cases of Korean companies poaching engineers from Japanese companies, they have offered part-time advisory positions for retired Japanese display engineers, who are normally over 60 years old, says Mitsuo Nakatani, senior display engineer at Hitachi, one of the biggest players in the PDP market. The art of using retirees South Korean companies have been scooping up retired Japanese for a couple of decades now, and they've mastered the art of getting the best people to help them, industry insiders say. The tradition started in the mid 1980s when Japan's semiconductor industry was still booming. Samsung, for example, started hiring retired experts as part-time advisers, says Shigeru Nakayama, senior adviser at Semiconductor Equipment and Materials International (SEMI). In addition, it's common knowledge that Korean companies offered part-time positions to retired Japanese semiconductor engineers, who would make weekend trips to Korea. The practice of using retired or part-time advisers still goes on today, says Nakayama, even though Korean semiconductor firms don't have much to learn from Japan anymore. "They do it just to keep a connection with the Japanese industry or just to keep their eyes open to the world," he says. "This is a huge difference from Japanese corporations."

By contrast, Japanese chipmakers are very conservative about exchanging engineers. Nakayama has been in the chip equipment industry for decades, but he says he can't think of one instance where a chip engineer at a traditional electronics manufacturer in Japan such as NEC, Toshiba or Mitsubishi Electric has jumped to an established rival. Some would jump to newer companies, such as Sony or Sharp, but jumping from one established company to another is practically unheard of in Japan. "Koreans are hungry for growth; they're never satisfied with the status quo," he says. "That's how they grow. We should learn from them like the US did during the 1980s." Over the past decade, Japan's electronics giants have gradually lost much of their competitive edge, while aggressive low-cost manufacturers from South Korea have made strong entries into global markets. Samsung now claims the world's second-largest share in the DRAM market after Micron technology, which has just won the top spot by acquiring Toshiba's main factory in the US. Toshiba announced that it was withdrawing from the business entirely -- the evidence indicates that Japan's glory days are long gone. And while Japan's drop in the chip market from more than a 50 percent market share in the mid 80s to about 25 percent today can't solely be blamed on inflexible hiring policies, Nakayama says those policies have definitely had an adverse effect on Japanese competitiveness. Now it's China's turn to catch up. Tsuyoshi Kawanishi, director at one of China's top two chip foundries, China Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp. (SMIC), says changes are on the way at Chinese manufacturers. Until recently, there were very few Japanese chip engineers in China, but the number has been growing gradually over the past few years, he says. For example, SMIC has over 400 foreign engineers -- most are from Taiwan, but recently more than 10 Japanese have joined the firm. Kawanishi says that Japanese chipmakers have sent technological advisers to Chinese firms for 20 years or so, but Japanese engineers being hired by Chinese firms is a new development. Kawanishi says Japanese engineers "used to complain that living in China would be too difficult, but they seem more willing to do so nowadays. Now that the Chinese chip industry is growing, I expect more engineers to follow suit." No bed of roses Record high unemployment at home has pushed more engineers to look abroad for jobs. And the jobs are there, especially in Asia, but the pay is not what the Japanese have come to expect. "Jobs posted to our agency range widely from JPY3 million to JPY10 million per year depending on experience and skill," says Hata at PaHuma. "Of course, high-paying jobs often require highly specific skills and knowledge." A large portion of the jobseekers have had at least a few years of experience living overseas for large corporations as elite expats, she says, and some of them enjoyed huge benefits that sometimes doubled salaries in real terms. "Most jobs we handle here are considered high-end jobs," she says, adding that many employees would have a housekeeper or two and a chauffeur. But even so, times have changed, Hata warns. Jobseekers tend to get disappointed with remuneration packages these days. "Benefits they used to enjoy are hard to get nowadays," she says. Ibaraki, the molding engineer, says times are getting tougher even in China. Most Japanese engineers working there are well off because living expenses are cheaper, he says, but competition among Japanese, Chinese and Taiwanese firms is heating up, putting pressure on companies to keep costs under control. "At least three molding factories I know closed down over the past few months," he says. According to industry sources, Taiwanese factories in the region are gaining ground on the Japanese because of a severe price war, prompting some Japanese manufacturers to stop using domestic factories and switch to Taiwanese or Chinese operations that can provide cheaper products. "Their production process is usually supervised by independent Japanese brokers, so they can maintain quality," Ibaraki says. "And if the quality remains the same, manufacturers couldn't care less whether parts are made by the Japanese or the Chinese." Packing up and moving out As Japan continues to hollow out, engineers may need to look far afield to find work. Ibaraki is one of this new breed of globally minded engineers. He's already pondering a move to Mexico, he says. "The (molding) industry is growing there. I wouldn't mind going there." But if Japan's best engineers are searching for work elsewhere, isn't the country at risk of a brain drain? SMIC's Kawanishi, who has also worked at Toshiba and Applied Materials, says he isn't worried about that. "Hollowing out of industries and an outflow of engineers are things that cannot be stopped," he says. "Japan only needs to think about ways to survive by focusing on value added technologies. I still believe Japan is very good at that." @ |

|

Note: The function "email this page" is currently not supported for this page.