A Silver Lining?

Back to Contents of Issue: March 2002

|

|

|

|

by Alex Stewart |

|

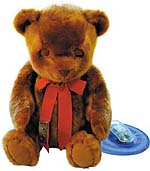

THE OPENING LINES OF Teddy Bear's Picnic could make a good jingle for the Matsushita nursing home, which opened last December in the dormitory town of Kourien, Osaka. The "big surprise"is that it is the first nursing home to be equipped with digitally linked robot teddy bears designed to be 'living' companions for the elderly. The step up from nursery tale fiction to real-life animation is due to progress in artificial intelligence (AI) technologies, which make it possible for objects to acquire the apparent ability to move and speak. THE OPENING LINES OF Teddy Bear's Picnic could make a good jingle for the Matsushita nursing home, which opened last December in the dormitory town of Kourien, Osaka. The "big surprise"is that it is the first nursing home to be equipped with digitally linked robot teddy bears designed to be 'living' companions for the elderly. The step up from nursery tale fiction to real-life animation is due to progress in artificial intelligence (AI) technologies, which make it possible for objects to acquire the apparent ability to move and speak.

"Sincere Kourien,"as the nursing home is called -- "Sincere" pronounced the French way -- is a 106-bed facility on land formerly occupied by a Matsushita company dormitory. The average age of the residents is 82. This elderly shock troop will be the test bed for Matsushita's next generation of home-care products for the very elderly, incorporating the latest in what higher processing speeds, digital communications and AI voice and image software can bring. Matsushita hardly leaps to mind as a leading provider of nursing home services. But things are different in Japan, where conglomerates provide the gamut of welfare services for employees. In Matsushita's case, it owns the Matsushita Memorial Hospital -- one of the major private hospitals in the Osaka area -- which provides it with the know-how to run an old people's home. The elderly care market probably has the same growth potential as the housing market did when Matsushita entered it in the 1970s. The tried-and-tested formula then, as now, was to set up a subsidiary, Pana Home, which would serve as a test bed for home-related electronics products. Sincere Kourien is also run by a separate business division. The market it is aimed at is becoming one of the largest in Japan. The country's population aged 65 and older -- the so-called 'silver' market -- is already 22 million strong, which is an increase of 20 percent since the last survey conducted by the Ministry of Public Management five years ago. As the Baby Boomers move along the demographic curve, the number of elderly will continue to rise. In only three years, according to the Ministry of Health and Welfare, it will total a top-heavy 25 percent of Japan's population. In the US, by contrast, only around 13 percent of the population is aged over 65 now, according to US census figures, and it will take until the middle of the century to reach current Japanese levels. Japan, then, is the major growth market for 'silver' goods and services. Matsushita is in a good position to deliver to this market since it is already strong in home automation and has a bent to develop products for a nation that is borderline obsessed with its bodily functions. For example, at the end of 2001, Matsushita launched the world's first bidet toilet which measures your body fat ratio. This clever bit of technology also tracks your height, weight and, wait for it -- gender, during a routine sitting. The technology looks great for markets with a fastidious concern for health. Matsushita's Sincere Kourien facility seems to believe that such demand exists. It gives rise to the possibility that the health-conscious and age-related markets could converge into a much bigger space that will spur Japanese creativeness to produce a slew of conveniences unimagined by more 'rational' Western markets. Japan was dubbed "The Robot Kingdom"in the early 1980s, when manufacturers embraced the installation of robot slaves in factories much more readily than their Western counterparts. The same thing seems set to happen as the economy shifts to services. The Japan Robot Association estimates there will be 11,000 service robots in use by the end of 2002, of which 65 percent will be in hospitals and nursing homes. In other words, there could be nearly 7,000 robots working alongside doctors and nurses as 2002 winds down. This would be a fast rollout, given the current early stage of marketing. Matsushita had only six teddy bear robots under testing at the Sincere Kourien home when it opened, but by the end of this year it will probably have one for each resident, and if market demand is strong, it will be supplying many more to hospitals and nursing facilities. Kuniichi Ozawa, the director of Sincere Kourien, is not trained to run a hospital; he follows the tradition of the first Matsushita salesmen sent to America, who learned what to do after being thrown in the deep end. He's the logical choice to run the facility because it was his idea to build a high-tech nursing home. As he explains it, "Two years ago we were well advanced on the AI and voice recognition side, and we needed an opportunity to test-market our technology, so I suggested building a digital nursing home." Ozawa had been working as part of the Health Care Development team within the Voice Recognition group at the Matsushita Keihanna Laboratories, located next door to the ATR Laboratories in the Keihanna Science City (see "Long-term Research,"September 2001, page 12). The laboratories are only a 30-minute drive from Kourien. ATR is the leading center for 'deep' AI research in Japan, and Matsushita's pet companion robot is based on a sensor doll first developed by ATR's Media and Information Corporation. The teddy robot, which is simply called 'Teddy,' is the fourth in a line of companion robots developed by Matsushita. The first one it developed was a cat robot called 'Tama' about five years ago. It was followed by 'Koma,' also a cat-type robot, then 'Wandakun,' a wombat, and finally 'Teddy.' Teddy is about 80 cm tall. On its back it carries a PC hidden in a backpack. The PC is linked to a server via a LAN cable. Cuddliness and engineering falter a bit here, but presumably one day all the electronics will be inside the bear and Bluetooth technology or similar will connect it to the nursing care Intranet. Matsushita is testing its teddy progeny on a group of eight elderly people in the Osaka suburb of Ikeda City. It has pressure sensors in its head and hands so that it can respond to physical contact. It can understand 300 words and reply to 2,000 sentence patterns. On the intelligence scale, this puts it somewhere on the level of a young child, and in terms of speech technology, among the leading examples of what is currently possible. For comparison, the NEC PaPeRo robot, which is one of the most advanced companion types, understands around 650 sentence structures and can speak around 3,000 words. 'Teddy' is more than a sit-alone bear, however. It also forms an integral part of the online health monitoring system at the nursing home, which is connected to the Matsushita Memorial Hospital. Each room is equipped with a video terminal and health monitoring system, allowing patients to communicate with a consultant without leaving their rooms. Family and friends can access information about their health condition by accessing the patient's records, which are held online and on an optical disk. 'Teddy' serves as an interface between the network and the patient. It has a CD-R in its backpack to which the server can download messages for Teddy to announce. When a family member calls, or emails, Teddy can first explain that there is a message waiting, and then play it back or read it out. In the first instance, it plays a recording of the voice, and in the second, it can read out the message in a synthesized voice. There are critics of the idea of putting an artificial life form between the elderly and the real world because they say it reduces the opportunity for real social contact. According to Matsushita, however, the majority of elderly people who have lived with their anthropomorphic companions have found the experience enjoyable. In a survey of 18 women and two men with whom Matsushita was testing the earlier generation wombat, it found that 95 percent could understand what the robot was saying, 65 percent felt comfortable living with the robot, 60 percent preferred to hear the robot's voice rather than a real voice, and 75 percent thought the robot was pleasant to touch. There is also in Japan a weaker barrier between animate and inanimate objects than in the West. For starters, what other developed country would consider it normal to introduce a robot to a production line using Shinto priests to wish it safe operation? The online teleconsulting system used in the nursing home was marketed first by Matsushita in the US for one year before it received permission to sell in Japan this year. From one of the residential rooms, I was able through the tele-link to watch people working in a consulting room at the Matsushita Memorial Hospital. The interface was very simple to use. The network stores normal data from checkups as well as other health data that is continuously gathered by sensors placed in 'Teddy.' For example, sensors record how long it takes for the elderly person to respond to a communication from the robot, the length of time the patient is occupying the toilet, or the time they spend lying on their bed. All of this helps alert the nursing staff and consultants to any changes in the state of their charges. This nursing home is so deceptively wired, it would make a high-security prison proud. The nursing director described the design of the home as 'barrier-free.' Unfortunately it reminded me a little of the cult movie, 'The Prisoner.' The residents feel no restrictions on movement, but in fact if they pass certain points they trigger a response which could close a door or alert personnel to the fact that someone has ventured out of the safe zone of the home. Although this has all the ingredients of Big Brother, in the case of elderly patients, some of whom are also suffering from senility, these restrictions are probably welcomed by those who entrust them to the nursing home's care. If the nursing home has a chilling resemblance to a prison-cum-holiday camp, then the robot teddy can help as an antidote. It is designed to be reactive, responding to touch or conversation, but does not have the ability to initiate either. In terms of AI technology, Matsushita is not trying to emulate the more autonomous level of behavior sought by researchers at the ATR labs. In fact it seems the main goal of the nursing home is to offer a barrier-free and emotionally warm environment for its residents. For example, the staff-patient ratio will be 2:3, which is the same as a normal nursing home. Ozawa explains: "Our goal is not to raise productivity but to provide a better service. We can provide services with our technology that would not be possible using only human beings. So in this sense we can say that we are offering a nursing care ratio of 3:3."The secret in part is the teddy bear robot, which talks and comforts and thereby provides extra help. Productivity is going to be an issue as Japan's population ages, but for the time being Matsushita's goal at Sincere Kourien seems more to pamper than to skimp. If its model is replicated widely, we may end our lives comforted by robot bears as well, possibly made or designed in Japan. The wider implications for Japan indicate a mixture of a bleak outlook for an economy based on an aging population and a silver lining as Japan rises to confront the challenge in its own unique way. @ Alex Stewart is principal of Kansai Capital Access, a venture capital advisory firm in Osaka, and a frequent contributor to J@pan Inc. His last article -- "Kyoto: A Blueprint for Japan?"-- appeared in the December 2001 issue. |

|

Note: The function "email this page" is currently not supported for this page.