Stemming the Suicide Tsunami

Back to Contents of Issue: April 2006

|

|

|

|

by John Dodd |

|

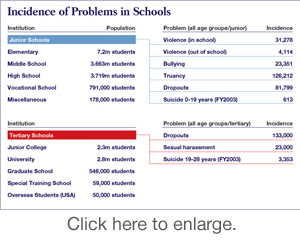

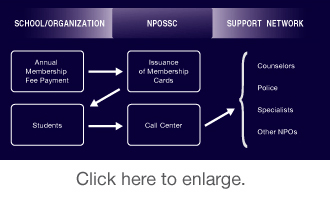

Some 3,500 university students commit suicide in Japan every year, in spite of the existence of hundreds of counseling and help lines in Japan. Perhaps there are too many, since they must all compete for meager funding in a society that has no habit of charity and giving. No money means bootstrapping and volunteers; so even a highly publicized suicide help line has few or no mental health professionals and trained counselors. As a result of their under-financed operations, most such organizations are too hard to find, too narrow in focus, too conservative, too nosey and local, or too religious, and thus turn off the youthful audience that they are trying to help. Some 3,500 university students commit suicide in Japan every year, in spite of the existence of hundreds of counseling and help lines in Japan. Perhaps there are too many, since they must all compete for meager funding in a society that has no habit of charity and giving. No money means bootstrapping and volunteers; so even a highly publicized suicide help line has few or no mental health professionals and trained counselors. As a result of their under-financed operations, most such organizations are too hard to find, too narrow in focus, too conservative, too nosey and local, or too religious, and thus turn off the youthful audience that they are trying to help. One man who wants to try to stem the flow of unnecessary suicides and bring some coherence to the world of counseling and help lines is Shinichi Ishizaki, a 46-year-old NPO professional whose background is working in groups helping the underprivileged and disadvantaged in society. His vision is to provide the many different organizations with a single contact point and help desk. Rather than replace the incumbents, his novel proposition is to work with them, acting as a "router" of information and remote diagnosis for callers in trouble. Ishizaki's particular interest is children and young people prior to their joining the workforce. He says that there are, in fact, few professional counseling resources for children in Japan, and no organization that covers the whole country. While he acknowledges that there are services like "Inochi no Denwa," Ishizaki feels that this and other publicized counseling services are either too focused on suicide prevention, too concerned about the consequences of giving advice and thus too passive, or staffed with well-meaning but unqualified, older volunteers, who are thus capable of making mistakes and superimposing their own value systems on much younger and more sensitive callers. Ishizaki plans a new service with dedicated lines and resources for different age groups. Kids, teens, and college students will be answered by professional phone counselors who will diagnose incoming calls -- directing the callers to appropriate services and organizations. Making remote diagnoses and knowing who to refer callers to requires an excellent up-to-date database, great networking efforts, and plenty of qualified child-related psychology and communication skills. According to Ishizaki, there is no comparable service in Japan. He intends for his service to be easy to find and use and also pay for itself. He will call it NPOSSC, which stands for Non-Profit Organization, School Support Consortium. Ishizaki came up with the concept of NPOSSC after looking at similar services overseas. He found a number of successful implementations that gave insight into the foundation of functionality of such an organization. In particular, he learned not to try to compete with existing organizations, but rather to overlay the better ones and provide a much needed front-end, aided by professional diagnosis of calls -- directing callers to appropriate resources. Additionally, in the case of younger children who are not mobile, the service could arrange for professionals to make home calls. Framework for a Successful NPO Ishizaki explains the primary objectives in setting up NPOSSC. "We have found three major keys to success. First, we need to have high visibility, so as to let children and teenagers know that there are counselors and services available. We plan to achieve this by focusing on the marketing and message -- educating Japan's youth that it's OK to seek out help. Fear of revealing one's inner feelings is a major problem in Japan that causes children to either become suicidal or irrationally angry. As a society we're experiencing an unprecedented wave of unvoiced frustration by children. "Second, we feel we need to be nationwide so that anyone anywhere can get help. This may seem obvious, but the thing is that while most of the existing counseling organizations are located in major urban centers, many of those people who need help are in fact located in more isolated areas, such as the northern prefectures. We plan to solve the coverage issue with a modern call center, possibly with cell phone texting services, and a comprehensive web site. "Third, we need to be sanctioned by the authorities and to work with organizations that are officially permitted by government to offer services. While the volunteer aspect of counseling in Japan is a great strength, in that it makes resources available in the absence of money, it nevertheless means that the quality and correctness of advice given is open to abuse and ignorance -- a particularly worrisome situation when dealing with impressionable children. When we discover a child in trouble, we want to make sure that we're not introducing another problem factor when we go in to help."  The Extent of the Problem The Extent of the ProblemEven as the number of students is falling, the incidence of student violence and other student-related problems is increasing -- at a rate of about 8 to 10 percent a year. Ishizaki reckons that although there were about 426,720 cases reported to the Ministry of Education or police, underreporting means that the actual size of the problem is 10 or 12 times this number. In Ishizaki's words, "This is an epidemic, and when we think about how children seek help when they're in trouble, we realize they're not getting help." Among the figures for overall violence, suicide, or self-violence, is also underreported, because of the reluctance of family members and sympathetic police covering such tragedies. Ishizaki reckons that last year there were close to 1,000 suicides by children aged up to 19, up substantially from the 613 reported in 2003. He comments, "It is unbelievable that in a nation such as ours, 20 children a week, one every 12 hours, are killing themselves because of their inability to cope with the pressures of growing up. Someone has to do something about this!" Ishizaki adds that the tsunami of suicides and school violence is largely due to the changes in how children interact with one other. Echoing the sentiments of child psychologists overseas, he feels that children desperately need reference figures around them: both responsible, caring adults and children with whom they can talk about feelings and act out their problems. But in this age of high-pressure education, juku (cram schools), both parents working, the breakdown of the extended family, and fear by parents of molestation reducing kids' chances to spend some "down time" together while walking home from school, it's no wonder that kids are taking these problems internally and finding themselves unable to cope. The eventual symptoms of not being able to deal with the pressure are manifested either as violence and callousness to others, or withdrawal and violence to oneself. How NPOSSC Will Work In putting together his non-profit business model, Ishizaki spoke to many friends and advisors, and discovered that investors have little interest in NPOs such as NPOSSC. They don't understand how you can get returns from a non-profit and furthermore find it hard to believe that a help line can constitute a business. But they don't realize that Ishizaki has, in fact, read the mood of schools and education authorities very well, and can create a potentially massive business out of helping others.  The secret to financial stability in his business model is to fund the organization through low-cost but wide-reaching subscriptions from organizations and parents who care about their kids' well-being. This means schools either signing up their entire student body for the service or marketing to the parents to do so. This is so much easier and commercially more viable than spending more money on in-school counselors or cleaning up the emotional mess caused by dead students. The secret to financial stability in his business model is to fund the organization through low-cost but wide-reaching subscriptions from organizations and parents who care about their kids' well-being. This means schools either signing up their entire student body for the service or marketing to the parents to do so. This is so much easier and commercially more viable than spending more money on in-school counselors or cleaning up the emotional mess caused by dead students. There is a precedent for a nationwide membership help-line organization, which appears to be an excellent model for Ishizaki: the Japan Automobile Federation (JAF). JAF is the indigenous equivalent of the Royal Automobile Association of the UK or the Automobile Association of the USA. JAF has successfully created a model whereby it is the contact point and trusted information source for drivers. And since no one else was willing to do it, it has built up a solid "signature" roadside breakdown service -- something that it now intelligently repackages and allows insurance companies to sell under their own brand. Ishizaki estimates that by using a similar model, he can charge schools up to JPY6,000/year per student, for each of the 15,551,000 students in the nation. This does not include the 548,000 students at vocational colleges and the more than 70,000 studying overseas. The question, he wonders, is whether families are willing to spend on the emotional well-being of their kids 20 to 30 percent of what they spend on their car every year. He is betting that as the falling birthrate stimulates the government to provide incentives for couples to have children, that at least some parents will appreciate the value of Ishizaki's service. The NPOSSC already appears to be striking a chord with education authorities. He has preliminary understandings with five Tokyo universities -- out of about 780 universities in Japan -- for a potential start-up user base of 5,000 students. Thus, from day one of establishment, the revenue base will be around JPY30,000,000 per annum. The subscriptions will be through on-campus sales, assisted through PR and direct marketing from university administration officers to the families of students. The NPOSSC marketing message will be straightforward and focus on parents' concerns about their children's safety and welfare. NPOSSC's value proposition is to be a backstop for troubled children and a neutral party they can turn to when depressed or otherwise in need of help. Using real life stories Ishizaki and his colleagues have already accumulated from their NPO careers, the message will also educate parents on signs of trouble and highlight that an ounce of prevention is much better than a child suicide. Dealing with the Competition Since NPOSSC intends to "front-end" kids' ability to get help and counseling, rather than offer specific counseling themselves (there will, however, be emergency services available), they really have no competitors. There are, of course, existing counseling services: five major nationwide networks, and another 20 or so smaller ones. But these are often self-absorbed, and do not adequately reach out to their target audiences, particularly younger children. They also often lack proactiveness and flexibility, for which reason they can't easily change their style to match trends and changes. For example, many of the organizations project an adult, conservative image, which puts off young callers who are most in need. Ishizaki's operation, in contrast, will be all about addressing the atti-tudes and concerns of his youthful audiences. The marketing, means of communication, and age and attitude of the counselor/referrers will offer sympathetic and non-judgmental access to the basic age bands of children, teenagers, and university students. For example, images to younger children will be friendly characters and staff who don't use big words, while for teenagers it will be texting and anonymity. Another problem with many counseling organizations is that Japan has few rules governing the whole sector. Anyone can be a counselor, and there are few if any college-level courses and/or qualifications for people wanting to specialize academically in the sector. According to Ishizaki, there is just now (as of January 2006) a move afoot to have counselors do a three-year course, and he expects that graduates will start appearing in the marketplace from mid-2009. But rather than wait that long, Ishizaki has a two-prong strategy to provide a high-grade service and response to troubled kids. Firstly, he has been approaching graduates of Dohto University, in Hokkaido, who are now practicing in Japan. He is certain that the quality of input given to callers, since it is based on the university's mental health and counseling qualifications, will be among the highest available in Japan. Secondly, he has enlisted the support of Professor Tasuku Oshima of Otsuma Women's University, a renowned expert in social welfare, who has agreed to establish a framework for in-house training for NPOSSC's phone counselors. Interestingly, Ishizaki and Oshima plan to make the training program of a sufficiently high level that in-house staff can use it as a foundation to build further formal qualifications at a participating university. The role that Ishizaki sees for NPOSSC is a brave one by Japanese standards. In a society where health problems are referred to doctors or are ignored, and mental health problems in particular are treated with drugs or not at all, he is attempting to provide a front-line diagnostics service for callers with problems. He plans to have phone counselors, or more accurately "problem navigators" [Ed: writer's term], who will take calls and, after speaking to the caller, assess what type of support they may need. From prior experience with another employer, Ishizaki expects that more than 80 percent of calls will be from people who are simply lonely or depressed and need someone to talk to. These people will be directed to an appropriate phone-counseling group in their area, and be encouraged to talk through their problems. Where a caller clearly has more serious problems, the call center phone counselor may call the police, a medical institution, a volunteer group or a hospital, or a school-teacher. The idea is to relieve the caller of having to figure out who to call, and instead connect them to the appropriate service. In some cases this will require the equivalent of mental telepathy to assess, but Ishizaki is confident that his response methodology, assessment questions, and conversation-pattern training will allow his team to pick up borderline and more serious cases. This is probably Ishizaki's greatest weapon in the fight for attention and funding. Because of the obvious risks and responsibilities involved, no one else provides a service with such definitive information, and no one is likely to do so in the near future. Ishizaki relishes the challenge of being first and in taking on the risks. If he can execute his vision well and get the initial funding that he is now in the process of raising, then NPOSSC may become Japan's main calling point by anyone in need. And Ishizaki will, in the process, become the most powerful NPO head in Japan. Ishizaki and NPOSSC are actively seeking expressions of interest from potential sponsors. His business model provides worthwhile income opportunities for backers, and can be viewed as not only an altruistic opportunity but a sound business investment as well. JI SEI Research Institute Co., Ltd. CEO: Shinichi Ishizaki Address: 7th Yumekobo Ginza Bldg., 4F, 1-27-11 Ginza, Chuo-ku, Tokyo 104-0061 Email: info@sei-j.com Web: http://www.sei-j.com (company) http://www.npossc.org (NPOSSC) |

|

Note: The function "email this page" is currently not supported for this page.