Corporate Sam Spades

Back to Contents of Issue: August 2003

|

|

|

|

by Roland Kelts |

|

|

The headlines and statistics about Japan's faltering economy merely skim the surface. Laid-off salarymen don suits and ties and head out to the nearest cafe or library to avoid confessing to their families. Accounting staffs are fudging figures and shifting employees into meaningless cubicles to elude the hammer of the buyout auction block. And the large parks and train stations of Japan's major cities are beginning to overflow with the blue-canvassed boxman lodgings of the homeless and unemployed.

To hell with conventional wisdom. When people are suffering, some opt to escape.

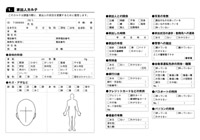

Approximately 100,000 individuals in Japan disappear each year, according to Dai Wakiyama, managing director of I.I. Service Co., Ltd, Japan's largest private investigation agency. Ten thousand of them have family members, friends or corporate bosses who are actively and sometimes painfully searching for them with the aid of I.I. Service's 300-person staff of investigative professionals. The company was founded by Wakiyama's father in January of 1974 -- during a relatively benign era in Japan's surge to economic superpower status -- and its 30 years of experience has clearly (and literally) paid off today: The number of missing persons in Japan has recently risen to annual record highs, in direct proportion to the elongation of the nation's recessionary economy.

I.I. Service posted JPY2.5 billion in revenue for the last fiscal year, 10 percent of which was operating profits. In short: Japan's economic failings have led to I.I. Service's astounding successes.

"We want to fill the gap with a responsible and "We usually find 90 percent of our clients," boasts Wakiyama, a fit and restlessly alert man with a studied eloquence in both Japanese and English. "Through our nationwide network of offices and 200 full-time investigators, we are able to satisfy most our customers, large or small."

Indeed, meetings in the company's headquarters several floors up in Shinjuku's Sumitomo building betray the power of private investigation in a country not known for transparency. The classic Sam Spade character of Dashiel Hammett's imagination was a hard-bitten, vaguely disreputable PI who nonetheless maintained a strict code of ethics, however unorthodox. But Wakiyama is a bold entrepreneur ripe with ambition and ideas.

"There's a third way," Wakiyama explains over a dinner in Kabuki-cho, Tokyo's paradoxically seamy and elegant red-light district. "We can't simply copy the American or European models, but we can learn from them. With all the fuss over Enron and WorldCom, and the messes at Resona and Mizuho here, we want to fill the gap with a responsible and culture-specific way to make Japanese companies accountable -- and more secure."

Both men figure that their expertise in private lives will extend to the public sphere of Japan's corporate behemoths, and thus they find themselves in an ideal position. "59.3 percent of all missing persons are men, and 74 percent are over 20 years old," says Amakasu. "The lack of communication in families is a serious problem in Japan. And that's also true of corporate families. Young people don't see a future, and when they leave home with their mobile phones, they don't really think they're leaving anything. Maybe the same is true of businesspeople who hide the truth, but don't really think they're lying."

The specs get dicey here. When I ask how they find the 90 percent of their clients, both men go silent. Then Wakiyama speaks up. "You know, a large proportion of them are actually hiding close to home. It's surprising. They don't really want to go far away. But at some point, they need money. They have to go to a bank or sign their name somewhere, and then we can trace them. Money," he adds with a subtle smile, "is a way to find almost anyone."

Time is Money

"Well, for some cases, especially the desperate ones, we accept a 10-day minimum," says Wakiyama. "Especially now, with people becoming desperate because of the economy. The police are no help, just as they don't help in the corporate sphere. They only get involved if something is obviously criminal.

The problems faced by the I.I. Service and D-Quest are the same impediments to growth everywhere in Japan. Systems are manifest in Japanese life, but few of them address serious problems efficiently, making real adaptive change virtually impossible. There is no licensing system for corporate or private investigators, for example, so anyone with a good faade and networking skills might conceivably get the job. This in itself debases authority.

What's more, actually seeking help of any type, whether you're a business or an individual, is seen as shameful. "There's the whole negative concept of therapy," Akamasu says. "Here in Japan, going to a therapist is an admission of failure. But we have to completely transform that perception, because we don't just want to find people, or save companies -- we want to actually change them."

"Less than 10 percent of our clients are repeat clients," says Wakiyama. "But that's still too much. It means that the root problem is not solved. And it's the same with big companies. You can't just fix corruption by firing one person. You need to have a whole approach." So how do you fix the problem?

"Well, we sometimes contact the person individually," says Amakasu. "But we have to deal with the individual. It doesn't matter if it's a company or a family. Individual attention is critical. That's what Japan needs at all levels."

D-Quest hopes to introduce a system of logic imported from the US. Japan, according to Wakiyama, has spent too long mired in a system of vagueness and cronyism. If transparency comes to Japan, D-Quest wants to lead the way.

"We're studying the licensing systems in the US," he says. "We want to import those standards. We need them here badly."

"Anyone can say 'I'm an investigator,'" adds Wakiyama. "Japan has no standards at all. In the US it's decided state-by-state. But we are now members of the Associated Licensed Detectives of New York State, and that's very important. We are studying their standards, and we want to bring those standards to Japan."

The history behind D-Quest's emergence is revealing. Resona's fiscal fiasco this past spring (resulting in government takeover and ownership) and the following near-collapse of Mizuho Bank were merely the most dramatic in a series of debacles. Risk management is an industry in the US and Europe that has tempered the arrogance of formerly untouchable firms, claims Wakiyama, and he's hopeful that the same effect can be achieved here.

"Most Japanese don't even understand this," he adds. "Be hard on businesses? Forget it."

The challenge is daunting. Japan has never had an impetus to adopt global infrastructures, and there's little evidence it is growing with dignity into new processes of self-examination.

But Wakiyama is optimistic. "We've had scandals at Snow Brand and Nippon Ham and now Tepco. Those disasters raise awareness. One bad habit is for Japanese companies to just get upset emotionally when something bad happens. But the real problem is that they haven't really prepared for it. This establishes the importance of risk management. And that's why we're here.

"But," he concedes, "the biggest problem we face in this country is this: The entire concept of [risk management] remains vague."

Unwritten Rules

"We want to introduce qualifications," Wakiyama says. "'Chief Risk Officer,' that kind of certification. We desperately need that here. Everything should be done authoritatively and by the book."

But that's not so easy in Japan. Both men see their domestic knowledge as Japanese and their long experience with Japanese psychological tropes as the features that distinguish them from overseas securities firms. In Japan, importing ideas from abroad takes some serious native wisdom, and this is where D-Quest comes in.

"Foreign securities firms sometimes don't really understand the Japanese way of dealing with people. There are many foreign companies in Japan, and there are many definitions of risk. But Japanese companies have many unwritten rules and regulations. D-Quest is going to target those companies."

Wakiyama and Amakasu aim to focus on the risks that an entity -- a company or family -- cannot predict. Especially in Japan, where the status quo rules, this focus is crucial. When Wakiyama says that the company is focusing on "human resources," I can't help but raise the spectre of September 11, 2001, when companies were suddenly required to reveal a very human face.

Wakiyama replies slowly, with a look of studious concern. "Well, as you know, many Japanese companies had offices in the World Trade Center. Although that incident happened in New York, it had great impact on Japanese companies. There was a lesson there: Expect the worst, and prepare for it. Quite a few companies here now have a disaster recovery plan because of 9/11. But having a plan is one thing. Making it work is another. That will be our job."

Legislation

Wakiyama and Amakasu believe that Tokyo will follow Washington's lead. "After the Enron debacle, there were help-lines established by law in the US," Amakasu says. "If that kind of legislation comes here, it will be immensely helpful to our cause."

Still, the spate of cover-ups and partial or non-existent disclosure policies in Japan leaves one less than hopeful. Wakiyama agrees. "In Japan, it's still totally unreal to let a third party listen to the bad news. They want to do it all internally at the company level, right up to the very top.

Japan's notoriously hierarchical corporate structure tends to prevent self-scrutiny. The CEO might talk to the CFO at the after-hours social event over a few glasses of sake, but that's where it ends. When I suggest that such behavior is sewn into the very fabric of Japanese culture, both men nod and sigh thoughtfully.

"It doesn't matter if it's a company "One of the reasons we're tying up with an English firm," notes Amakasu, "is that the attitudes there may more closely resemble the habits here." He cites the discretionary nature of English culture (the classic "stiff upper lip" of English endurance and circumspection) and suggests possible parallels to Japanese notions of tatemae and honne -- the embarrassment-saving rituals of the public sphere (and the polite banter of mutually assured repression) versus one's honest feelings, which just might be the truth.

Legislation in the UK called "Turnbull Guidance" has made corporate governance a top priority for English companies. "It literally requires all UK-listed companies to make clear and lucid statements about how they prepare for risks. And it's open to the public."

Numerous media reports in mid-June provide ample evidence that the Japanese public is becoming more vocal. Despite the still embryonic state of the securities industry, shareholder activism is on the rise. Activists disrupted meetings across the country, most notably at Tepco's confrontation in Tokyo, where shareholders reportedly demanded that the company reveal the reasons behind its sudden energy crisis in the nation's capital region. Risk management is a crucial first step in satisfying stockholders whose needs are not currently being met.

"By being a corporation's third-party helpline," Wakiyama reasons, "we can actually raise the stock value of the entire company."

Danger

Still, just prior to their late June US tour to promote D-Quest and establish contacts and alliances, I ask Amakasu why he designed an itinerary that has the two men soaring from coast to coast, then south to Texas, hitting five cities in 11 days before returning to Tokyo. Won't that be exhausting?

"We're a securities firm," he replies. "So having the two directors out of the country at the same time is kind of ... I mean, what if the plane goes down?" He shrugs and smiles. "That wouldn't be very secure at all." @ |

|

Note: The function "email this page" is currently not supported for this page.

"YOU CAN RUN, BUT you can't hide," runs the conventional wisdom. But you can always try to hide -- especially when you've just lost your job in a tight economy and can't face your wife and children in the morning, or you've gone bankrupt and slipped into debt to some loan sharks issuing knife-edged threats, or your spouse is beating you within inches of your life, or you're about to lose everything, absolutely everything, and you know you're not going to get it back.

"YOU CAN RUN, BUT you can't hide," runs the conventional wisdom. But you can always try to hide -- especially when you've just lost your job in a tight economy and can't face your wife and children in the morning, or you've gone bankrupt and slipped into debt to some loan sharks issuing knife-edged threats, or your spouse is beating you within inches of your life, or you're about to lose everything, absolutely everything, and you know you're not going to get it back.

Last year, Wakiyama published a book, How to Find Missing Persons, profiling his career and his company's activities and assaying Japan's current social and economic dilemmas. With his successes at I.I. Service, he formed a new company called D-Quest in 2000, devoted solely to securities concerns in the corporate sector. D-Quest is Japan's most adventurous corporate governance firm (with a medium-term goal of JPY500 million in revenues), and Wakiyama and his new partner, former Yokohama banker and Duke University-educated Kiyoshi Amakasu, aim to make it entirely unique. In late May of this year, D-Quest inked an alliance with Carratu International, one of the UK's oldest and largest corporate investigation firms. At the end of June, Wakiyama and Amakasu embarked on a five-city tour of America in 11 days to seek new business opportunities.

Last year, Wakiyama published a book, How to Find Missing Persons, profiling his career and his company's activities and assaying Japan's current social and economic dilemmas. With his successes at I.I. Service, he formed a new company called D-Quest in 2000, devoted solely to securities concerns in the corporate sector. D-Quest is Japan's most adventurous corporate governance firm (with a medium-term goal of JPY500 million in revenues), and Wakiyama and his new partner, former Yokohama banker and Duke University-educated Kiyoshi Amakasu, aim to make it entirely unique. In late May of this year, D-Quest inked an alliance with Carratu International, one of the UK's oldest and largest corporate investigation firms. At the end of June, Wakiyama and Amakasu embarked on a five-city tour of America in 11 days to seek new business opportunities.

Thirty of I.I.Service's investigators are women over 40 years old, and their value, according to Wakiyama, is self-evident. The women attempt to provide therapeutic services that will prevent another disappearance, another attempt to run and hide.

Thirty of I.I.Service's investigators are women over 40 years old, and their value, according to Wakiyama, is self-evident. The women attempt to provide therapeutic services that will prevent another disappearance, another attempt to run and hide.

In addition to their international scope, D-Quest brings to the table a plethora of cultural and psychological insights, mostly gleaned from their years as PIs dealing with families and individuals on the lam. Amakasu talks at length of the failure of the Japanese educational system to meet the needs of its students -- the very fuel of any economy's future -- by ignoring their needs and dismissing their cries for help. He sees the same failures damaging the corporate world, where companies ignore their staff members and remain oblivious to accumulating troubles until corruption and carelessness lead to collapse.

In addition to their international scope, D-Quest brings to the table a plethora of cultural and psychological insights, mostly gleaned from their years as PIs dealing with families and individuals on the lam. Amakasu talks at length of the failure of the Japanese educational system to meet the needs of its students -- the very fuel of any economy's future -- by ignoring their needs and dismissing their cries for help. He sees the same failures damaging the corporate world, where companies ignore their staff members and remain oblivious to accumulating troubles until corruption and carelessness lead to collapse.