A Capsule Camera to Save Stomachs

Back to Contents of Issue: July 2003

|

|

|

|

by Ayai Tomisawa |

|

WHAT IS AN IDEAL endoscope supposed to look like? It has been more than half a century since the world's first gastric endoscope was introduced by Olympus Optical Co. Finally there has been improvement: A wireless, compact and disposable endoscope developed by a Japanese venture company is expected to debut on the market this year. WHAT IS AN IDEAL endoscope supposed to look like? It has been more than half a century since the world's first gastric endoscope was introduced by Olympus Optical Co. Finally there has been improvement: A wireless, compact and disposable endoscope developed by a Japanese venture company is expected to debut on the market this year.

Compared to a traditional endoscope, which is often awkward and painful to insert, the new capsule endoscope developed by RF Co., Ltd. can be swallowed by a patient like a vitamin pill and is capable of transmitting images of the patient's body while traveling through the intestines, until it is excreted naturally and painlessly.

"I felt like I was in hell," says Akiko Miyuki, 26, of her first experience traditional gastric endoscopy. "A tube like a long, hard water hose was squeezed into my throat until I wanted to vomit. I knew the screening procedure took less than 10 minutes, but it felt like more than an hour."

As tiny as a pill, the Norika3 Because Japan has an unusually high incidence of gastric cancer compared with other developed nations, early detection of the illness is invaluable. More people are undergoing endoscopic examinations every year, according to Ryuji Nagahama, department chief of the doctors' office at the Foundation for Detection of Early Gastric Carcinoma, a Tokyo-based medical institution which conducts 5,000 endoscopies a year. "Ninety percent of gastric cancers detected at our institution are at an early stage," says Nagahama.

Another gastric problem that needs to be detected at an early stage is obscure digestive tract bleeding, suspected to be located in the small intestines. One of the problems that doctors have in the gastrointestinal tract is that there is a large part of it -- most of the small intestines -- that they cannot access with standard endoscopes.

"We can access the upper end of the small intestines, because we have instruments long enough to go into it, but that only takes us so far because there are so many loops, and it's just technically not feasible to go any further. We can't access the small intestine in the same way that we can look at the other parts of the gastrointestinal tract," says David L Carr-Locke, president of the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and director of endoscopy at Brigham & Women's Hospital.

"The capsule is for specific indication. Obscure bleeding is the main reason we use it," Carr-Locke says of an existing, battery-operated capsule endoscope used in the United States. Carr-Locke, who is also associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, adds: "The problem of the battery is that it takes up space, and the capsule has to be a little larger to accommodate it. I know that one of the features of the new Norika capsule is that the power is transmitted from outside, not from the capsule itself, so it can be made a little smaller."

"Though it hasn't been in practical use yet, we've received loads of requests from people wanting to become monitors for experiments, even one from an 80 year-old woman," says a company official.

Established in 1993 in Nagano, RF began by producing wireless cameras targeted for the broadcasting industry, using a combination of microwave and charge-coupled device (CCD) technology.

In 1997, the company entered the medical industry when it developed a wireless intraoral camera, a dental instrument that dentists use to show patients the inside of their mouths on a monitor during treatment.

RF now enjoys about an 85 percent share of the world's wireless intraoral camera market. The company hit upon the idea to develop Norika3 in 1997, when it joined the Japanese Experimental Module Project, a venture operated by the National Space Development Agency of Japan to monitor the growth of plants in a manned spacecraft.

According to a company official, the project triggered the idea of producing a wireless camera that would allow researchers to monitor the inner bodies of astronauts -- which eventually led to cutting-edge technology for diagnostics and treatment of the gastrointestinal tract.

Although the company says it is still preparing to conduct clinical studies with other medical institutions, it expects to market the Norika3 by the end of the year both in Japan and overseas. It will accommodate a CCD camera of 0.41 megapixels and is likely be initially marketed at $100. The company official says it will eventually be sold at around $40 when it is mass-produced.

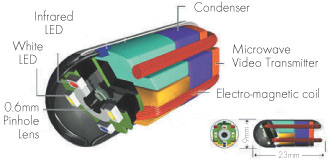

The capsule moves painlessly through the gastrointestinal tract while transmitting color images on a real-time basis. The device accommodates a plastic CCD camera with a 0.6 millimeter lens as well as four Light-Emitting Diode (LED) flashing devices to supply light in the dark intestines. The camera can transmit up to 30 images per minute, as long as the patient is wearing the vest that transmits microwaves to the capsule.

In a few years' time, RF officials hope to sell 5 million units annually within Japan, though they concede that the capsule endoscope will not completely replace traditional methods of endoscopy. "It will probably be used only in combination with traditional endoscopy," says a company official.

Distributors of the conventional endoscope agree. "Since it can get into parts of the gastrointestinal track inaccessible to traditional endoscopes, I'm sure it will be widely used in the future," says an official at Fujinon Toshiba ES Systems Co. "But a capsule endoscope cannot do everything; it will be a device that complements the standard techniques."

RF now has 105 employees and plans to go public in two to three years. It expects to post JPY2.7 billion in sales for the fiscal year that ended in May 2003, a year-on-year increase of 80 percent. @

IF PICTURES OF THE new "Stomach-cam" look like something from science fiction, it's probably because they are. Like so many new pieces of technology -- video phones, pocket computers and DNA screening -- the world saw them first in the pages of cheap novels and B-movies.

It is a tribute to the pace of change that devices which just 10 years ago were the stuff of fantasy are now leaping from the designer's drawing board into the real world. When it comes to the concept of steering a craft through the flesh-and-blood maze of the human body, the idea itself is nearly 40 years old. Isaac Asimov, the acknowledged master of science fiction, wrote of just such a journey in his blockbuster The Fantastic Voyage.

Since then, the fascination with our insides has been taken up by Hollywood. Asimov's epic was turned into an Oscar-winning film in 1966 and showed the many perils lurking in human anatomy. In the years that followed, countless other movies have explored the wonders of "inner-space." Filmmakers have thrown all their might behind the special effects that make these scenes possible, but in the future they may not have to. If The Fantastic Voyage is ever remade, the director won't even need special effects -- just an endoscope.

|

|

Note: The function "email this page" is currently not supported for this page.

As tiny as a pill measuring just 9 millimeters in diameter and 23 mm in length, the Norika3 capsule endoscope developed by RF is uniquely painless.

As tiny as a pill measuring just 9 millimeters in diameter and 23 mm in length, the Norika3 capsule endoscope developed by RF is uniquely painless.

Science fiction, science fact

Science fiction, science fact