Two Japans

Back to Contents of Issue: May 2003

|

|

|

|

by Takehiko Kambayashi |

|

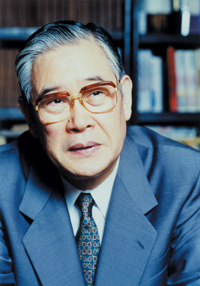

VISITORS TO TOKYO OFTEN say they don't get any sense of a recession in Japan's capital city. Immaculate subway cars pull into stations every two to three minutes during rush hour, consumers buy all sorts of expensive brand-name goods and construction cranes dominate the skyline. The city seems alive and thriving. Minoru Morita, a political analyst and regular commentator on national TV networks, says anyone who visits only Tokyo may well get that impression. But travel outside the capital and you'll quickly see that there are two Japans. Morita, chairman of the Morita Research Institute, spoke to our reporter about the widening economic gap between the capital city and the provinces.

"What the administration I understand you have a lot of opportunities to see different parts of Japan as you give lectures throughout the country. Can you tell us what you are seeing outside Tokyo these days? In the provinces, the economic situation has become much more serious. The only prosperous place in Japan right now is Tokyo. Many people say that there are now two Japans -- Tokyo, in a bubble, and the provinces, in a deep recession. When you say "Tokyo Bubble," what do you mean? Tokyo is isolated and insulated from the rest of the country. This is primarily a result of the Koizumi cabinet's policies. It has drastically tightened its fiscal control over the provinces. The administration makes it clear that it will stick to its policy of fiscal restraint in the future so local governments are being forced to merge with each other. They simply cannot operate under such policies. Second, during the period of rapid economic expansion, the provinces followed Tokyo as a model. Main streets named "Ginza" are everywhere. But the protracted economic downturn has hit the provinces hard. Many stores along Main Street are shuttered even in the daytime. Leading companies are abandoning the provinces and converging on Tokyo because there are more business opportunities in the capital. This abandonment is happening even in big cities like Nagoya and Osaka. It is only in Tokyo that you can make good money. So whenever leaders of Osaka-based Matsushita Electric go to meetings, they are pressured by people who say things like, "Perhaps Matsushita is the only corporation that is not going to Tokyo. Why?" The provinces are being hollowed out. When I was invited to Kagoshima a year ago, the city seemed to be deserted. I said to my hosts, "We see very few people, don't we?" They told me there is only one place where people gather, and they took me to that place. It was a local employment agency. Wherever you go outside Tokyo, you notice the same thing: The only place where many people meet is the local employment agency. As the number of jobless keeps increasing outside Tokyo, they say the jobless rates there are actually higher than the national average by 2 to 3 percent.

As local economies deteriorate, even the yakuza and taxi drivers are coming to Tokyo. Tokyo draws those looking to prosper. On the other hand, while the provinces have lost prosperity, puritanism has resurged. Thus Japan has polarized: The provinces are poor but regaining their sense of morality, and Tokyo is prosperous but morally adrift, focused completely on making money and attracting more crime. Once, many Japanese embraced the idea of an egalitarian society. It seems, however, that more and more politicians, scholars and journalists are writing off egalitarianism these days. Yes, they are increasing. The Koizumi cabinet has made significant progress in polarization: the rich and the poor; the prosperous megalopolis and the struggling provinces. They have destroyed egalitarian society. The government's policies are based on the idea that Japan is unable to realize its potential but that the Japanese are naturally more able. In the late 1970s, an American scholar, Ezra Vogel, mockingly flattered Japan in a book called Japan as Number One. Many Japanese, including top scholars, took this seriously and became flushed with Japan's importance. It's just like a pinch hitter coming in with the bases loaded who closes his eyes, swings and happens to hit a grand slam. The Japanese mistook dumb luck for true ability. Japanese bureaucrats continue in this misconception. In short, what the administration is trying to do is turn Japan into Toyota. It is trying to make the rest of Japan follow the example of its only successful business model. In order to do this, the government makes no bones about slashing workers' wages and welfare and creating more unemployment. As you know, it's absolutely impossible for all of Japan to become Toyota. When I visited Toyota city in Aichi prefecture the other day, locals told me that while Toyota Motors has flourished, Toyota city has not. Many people say Japan should decentralize. Do you see decentralization happening in the provinces? The "decentralization" the government promotes is false. It is reinforcing centralization under the slogan of "decentralization"; the government is telling the provinces to follow "decentralization plans" made by the central government. Major newspapers and networks accept these plans for decentralization. But in the provinces, they are seen as centralization. It is sad but true that the majority of the public also misconstrues these plans as decentralization. However, a minority believes that the provinces need to achieve a true decentralization of power -- and these people say the first step should be to start turning their back on the national government. @ Takehiko Kambayashi is a Tokyo-based freelance writer and a contributor to J@pan Inc. |

|

Note: The function "email this page" is currently not supported for this page.