JIN-521 -- Dawn Of The East West IT Cold War

------------ PBXL is Business Communications --------------

#2 in a Series - 'Service & Support in the Cloud'

Use CLOUD CALL CENTER POWER

TO GET INDEPENDENT AGAIN!

Insourced service and support desks enabled by PBXL's

Cloud Call Center have the functionality of outsourced

operations... at a price small & medium sized businesses

can afford.

If you have between 3 and 30 operators, and you contact

us in March, you will receive a credit for two months service.

PBXL, an official Salesforce Japan Partner, is now offering

another first - the subscription based Cloud Call Center.

What does the Cloud Call Center mean for Support?

Far lower cost of operations. Better operators (in-house staff

who really DO know your business). Satisfied Customers.

Use ACD, IVR & Database Screen Pops with ease. Big company

technology to power sales results & better reports.

There are no hidden software, hardware or IT costs.

Yes, your staff can perform better without big expense.

Get the full picture today.

For information, fill out the inquiry form at

http://en.pbxl.jp/about.php or call: 03-4550-1600.

------------ PBXL is Business Communications --------------

J@pan Inc Newsletter

The 'JIN' J@pan Inc Newsletter

A weekly opinion piece on social, economic and political trends in Japan.

Issue No. 521 Monday, March 29, 2010, Tokyo

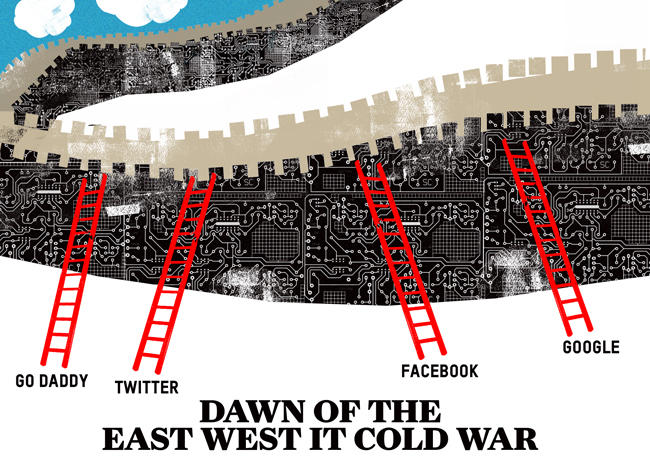

China's Alibaba Group is on the verge of launching a joint online commerce venture with Softbank, Baidu this month announced plans to launch a business-to-consumer online site with Rakuten, and U.S. auto giant Ford Motors just sold one of its crown jewels of safety and customer loyalty, Volvo, to the China-based Zhejiang Geely Holding Group for $1.8 billion dollars. China Inc. is knee deep in deal making mode. But despite the aggressive international deals, recent events surrounding IT concerns such as Google, and others, have revealed what may be the first skirmishes in what we'll call the East West IT Cold War.

Last week Google announced that it would officially shut down its Google.cn website due to censorship concerns. The move follows Google's previous statements leading up to the closing that featured, in addition to a lofty entreaty against censorship, a rather vaguely worded blog posting regarding security intrusions that never directly accused the Chinese government of supporting/sponsoring IP theft, but implied enough that even the most casual reader could grasp Google's ciphered assertions—China is stealing our IP and we can no longer operate under such conditions.

That Google attempted to couch the move in the very Western cloak of "fighting for free speech" was a clever, well calculated strategy that has convinced a large portion of Silicon Valley that the company is engaging in yet another aspect of its "don't be evil" motto. And, in what feels like a subtle call to the Web community for activism, the company has even posted a page designed to update users as to which Google services are currently available, or blocked in China (www.google.com/prc/report.html). Following Google's lead, the U.S.'s two largest domain name registrars, GoDaddy and Network Solutions, also announced last week that they would pull out of China, citing censorship concerns related to China's new domain registration policies.

The new policy holds that registrants must provide a color, head-and-shoulders photograph of themselves as well as a Chinese business registration number and physical, signed registration forms. Christine N. Jones, general counsel of the Go Daddy Group told the Washington Post, "The intent of the procedures appeared, to us, to be based on a desire by the Chinese authorities to exercise increased control over the subject matter of domain name registrations by Chinese nationals," adding, "We decided we didn't want to be agents of China."

While the issue of censorship and privacy in China is indeed ripe for debate, there is a central problem with the moral grandstanding of Google and company—all of these IT firms have operated in China for years, previously adhering to the country's censorial guidelines without public complaint. Why find a moral compass now? If Google truly disagreed with the censorship policies of the Chinese government, why did they even agree to adhere to them in the first place?

Why? The most reasonable answer is two-fold. First, it's likely that Google thought that, after several years of plugging away at rival local search company Baidu, it would have more than a mere 30 percent share of China's search market. Trading dominant market share for a few years of censorship probably seemed like a good gamble at the time. Second, Google didn't anticipate the piracy of its intellectual property. Reports from security experts indicate that Google's recent security breach included the loss of IP, the very heart of Google's product value. Making the determination that, like other IT firms before it, Google's code would slowly be siphoned off by Chinese hackers and possibly woven into the competing products co-owned by the Chinese government, it's reasonable for the company to conclude that there is really no hope of ever gaining significant market share over local, state-sponsored competitors. In my estimation, these two points represent a more honest (albeit, somewhat cynical) view of why Google gave up on mainland China.

Indeed, even the wildly popular Twitter microblogging service has largely been replaced (rapidly) by a nearly identical, Chinese version of the service called Weibo (http://t.sina.com.cn), a service created by Sina, China's most popular Web concern with over 94.8 million registered users. The heavily censored Weibo platform not only functions exactly as Twitter does, but the service even copied the now iconic sky blue branding of the often blocked Twitter, an aesthetic point probably designed to make the switch go down easier with Chinese users.

Because of various sensitivities and complicated business relationships, a surprisingly large amount of Western businesspeople often avoid the topic of doing business "China-style." Perhaps the most frank comment I've read in recent months came from business veteran and Beijing-based expat Bill Bishop who recently blogged (http://digicha.com) his market entry advice for Facebook and Twitter: "Don’t bother trying to come into China directly. Your services are far too subversive to be approved in the current environment. Even if you were allowed into the country, you would be chewed apart by large, scrappy local competitors like Oak Pacific, Kaixin001, Sina and Tencent. And the ethical and public relations minefields would be too great a distraction for your young companies. Instead, provide free VPN and other filter-bypassing services…"

Bishop, an American who started working in China back in 1989, offers a frank nostrum that would force Chinese consumers of certain Western IT products to either become soft-hackers, or simply accept the censored, Chinese versions of these services. While there are sure to be a large number of internationally curious and activism-oriented individuals in China inspired to use VPNs to access prohibited Western services, based on the history of the Web in China, it's far more likely that the local IT products will continue to dominate with their censored versions.

Although it is true that some Western IT concerns are reconsidering their fortunes in China in the wake of Google's bold move, if Google and company think the rest of the West's business community will follow their move, driven by moral imperatives, or that China is about to change it's policy simply because some Western IT firms won't play censorship ball, they are sadly mistaken. In fact, a quick review of the U.S. pavilion website for the upcoming Shanghai Expo 2010 reveals that Microsoft, Intel, and Dell are all listed as enthusiastic sponsors of the China-based business event. The credo "when in Rome…" has never been more apt than when talking about doing IT business in Asia. Anyone acquainted with the numerous failed attempts of American IT brands hoping to penetrate Japan's unique market are aware of this.

Responding to the recent censorship uproar in China, Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates opined, "You've got to decide: do you want to obey the laws of the countries you're in or not? If not, you may not end up doing business there." It should be noted that, despite Gates' lack of impassioned moral outrage, Windows OS is one of the most pirated products in China, with illegal copies selling for just $1 on the street.

In an interview with the UK Guardian, Google co-founder Sergey Brin responded to Gates' statement by saying, "I'm very disappointed for them in particular… As I understand, they have effectively no market share [in China] – so they essentially spoke against freedom of speech and human rights simply in order to contradict Google." Does Gates want his rival search engine Bing to beat Google in China? Sure. But making the issue a moral discussion rather than a measured business analysis is where Brin's credibility falls short. Gates is correct. In the end, you follow a country's laws or you don't do business in that country, it's as simple as that. If Brin had a serious moral problem with China's policies, Google never would have set up shop in China in the first place.

As for the future of Western business in China, and Asia in general, we can look to a couple of factors for guidance. Let us first recognize that in midst of all this talk about Google leaving China, few, if any, Western firms engaged in using Chinese labor to manufacture durable goods (computers, apparel, etc.) have announced solidarity with Google's approach. It's business as usual for most Western durable goods concerns. Due to the cheap labor and an established system of efficiency, this relationship is unlikely to change in the near future.

The margins of this Cold War will likely be restricted to the area of intellectual property, discreet and unique code, and ideas that can programmed and distributed. In short, the question of whether to/how to do business in China, and Asia in general, is most relevant in the short term to IT businesses. Learning the local color, the unspoken nuances, and the agreed upon business practices (fair or unfair to one's Western point-of-view) cannot be avoided. To attempt to shoehorn Western business ethics and SOPs into China and Japan is an effort that is doomed to fail, and only arrogance and/or ignorance will push such efforts forward.

-Adario Strange

------------------ ICA Event - April 15 -------------------

Speaker:

Jean-Luc Creppy General Manager-Quint Wellington Redwood

Topic:

Reevaluating & Refocusing IT

Details: Complete event details at http://www.icajapan.jp/

(RSVP Required)

Date: Thursday, April 15, 2010

Time: 6:30 Doors open, Buffet Dinner included and cash bar

Cost: 4,000 yen (members), 6,000 yen (non-members)

Open to all - Venue is The Foreign Correspondents' Club of Japan

http://www.fccj.or.jp/aboutus/map

-----------------------------------------------------------