The Labor Market -- Poles Apart

By Wataru Nakazawa

The stratification of the Japanese workforce.

Over the 2008/2009 holiday period, the reality of Japan’s non-regular employment system set in. The nation tuned in to the television news to see report after report on a temporary village of haken workers (dispatched workers) camped in Hibiya Park in the center of Tokyo. The flood of newly unemployed and homeless entered the park as the fallout from the Lehman’s collapse and the unprecedented recession that followed spread to factory floor. The contracts of many workers dispatched to manufacturers were canceled and since these dispatched workers were often provided with company accommodation, they lost not only their jobs but also their homes.

Frequent instances of inequality between regular workers and nonstandard workers have emerged in recent years. Nonstandard workers in this context include part-time workers, contract workers, and dispatched workers. In the Japanese context, the nonstandard workers do not always have short working hours as compared with the regular workers. In other words, many nonstandard workers have to perform the same tasks as regular workers but do not enjoy the same working conditions—they are not strongly protected by the law and the social security system.

Originally, the majority of part-time workers in Japan were homemakers who finished childrearing and wanted to compensate for the lack of a household income. Dispatched workers were restricted to work in the professional areas. However, a new class of workers arose among the youth in the 1980s. They were called “freeters” and have garnered much attention since their conception. Moreover, they were held in high regard in the bubble economy. The number of dispatched workers has also gradually increased owing to the pressure of deregulation and diversification of value for work. Dispatched workers have been open to manufacturers since 2003, and this change has caused the situation in which these haken workers found themselves in recently.

On the other hand, Japanese enterprises traditionally welcome new graduates because they encourage employees to develop their skills through on-the-job training. Under this condition, laborers have an incentive to remain in the same company because their skill may be useless if they moved to another firm. Furthermore, their salary would increase if they worked for a longer time in the same company. Therefore, employers wish to determine the trainability of applicants. The educational credentials and academic grades are often regarded as the measures of trainability. Hence, there has been a strong tie between schools and enterprises, and the low youth unemployment rate has been explained by this institutional system.

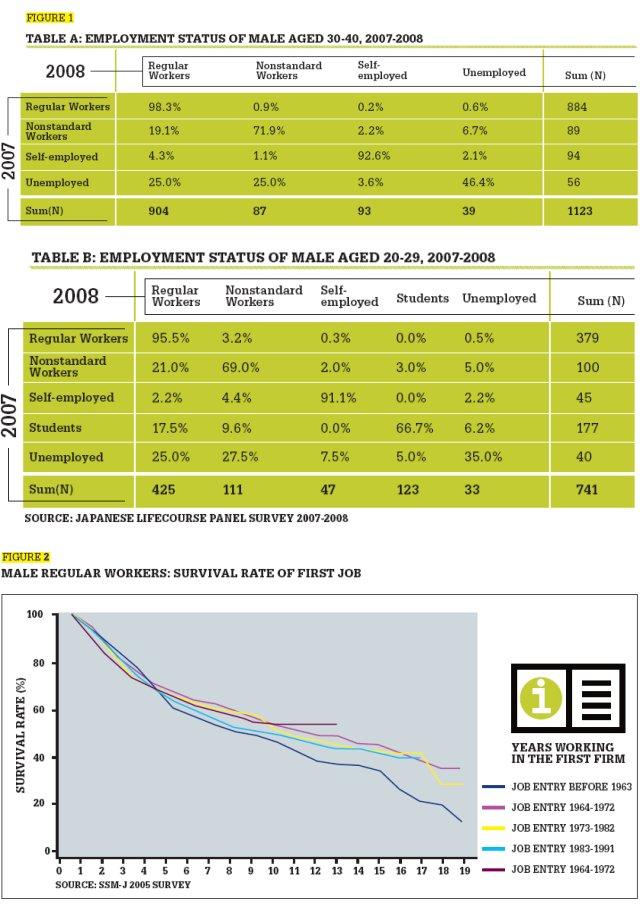

In the meantime, the tasks of nonstandard workers are often restricted to a simpler area of work, or are not appraised on the same level as that of regular workers. Employers often regarded these nonstandard workers as those who could not adapt to social activities. Enterprises had no reason to employ such temporary workers, and this made it difficult for them to become regular workers. In addition, the adverse economic condition spurred this trend. Consequently, the salaries of nonstandard workers do not increase, and they only continue to age. Thus, the economic differentials between regular workers and nonstandard workers expand. Since the cost of children’s education is high, the nonstandard workers face uncertainties with regard to their marriage, childbirth, and child-rearing. (Figure 1)

Is the Japanese employment system, which is characterized by lifetime employment, really destroyed? Does the Japanese labor market become more fluid? The answer is complicated. The reference to lifetime employment can be clearly observed in the public sector and the nation’s large enterprises. However, that is not applicable to the small or medium enterprises. Figure 2 indicates the survival rates of first jobs for regular male workers. The data source is the Social Stratification and Social Mobility (SSM) survey conducted by Japanese sociologists in 2005. The xaxis reflects the number of years since they started their first job, and the y-axis, the survival rate. If we compare the different job-entry age divisions, we can barely find any differences between the survival rates among the generations. Although many people indicated that the Japanese labor market has become more fluid during this decade, the survival rate of the youngest job-entry division is slightly higher than the others. From an economists’ point of view, it is natural that employees tend to remain in the same company in order to avoid the risk of unemployment during grave economic conditions. Furthermore, in recent times, late marriage and the transition to a gender-equal society have begun to promote a longer duration of first jobs for women. But there is a reason that people feel that the labor market has become more fluid. The number of nonstandard workers who tend to work for a short term has gradually increased since the 1970s. The rate at which this number is increasing has been growing since the 1990s, particularly among women. In other words, the reason for fluidity can be explained by the increasing proportion of nonstandard workers.

Why has the employment problem become the center of attention in recent times? One reason for this is the “aging freeter.” The Japanese government defines freeters as nonstandard workers aged between 15 and 34; however, there are many nonstandard employees who are freeters and over the age of 35. Although they escaped the governments’ definition of freeters, their situation does not change. Besides, the older they get, the more difficult it is for them to secure jobs. That is to say, the risk of unemployment becomes higher, and it becomes more difficult to escape from the confinement of nonstandard jobs. In addition, most of them live in solitude and become despondent over the future. We should also consider that Japan has one of the highest suicide rates among the industrial countries (although not all causes of suicide can be blamed on serious employment problems). Figure 1 shows males’ working status between 2007 and 2008 based on the Japanese Life Course Panel Survey conducted by the Institute of Social Science, University of Tokyo. The target of this survey comprised Japanese people aged between 20 and 40. During this one year, most males remained in the same employment status. Approximately only 20 percent of nonstandard workers in 2007 could become regular workers in the following year, and it was more difficult for men over 30 to escape from unemployment than men in their twenties.

The second reason for this employment situation is that it seems to bipolarize the labor market into regular workers and nonstandard workers. This division often causes the expansion of economic differentials. Inequality, economic differential, and poverty denote the existing problems in Japanese society. The concept of “working poor” is now well known to Japanese society because NHK TV and other mass media has started to report on the difficult life of nonstandard workers. The working poor can often be observed among the low socioeconomic status groups, and these adverse economic conditions often lead to serious familial problems like divorce. Once a person becomes one of the working poor, it is very difficult to escape from that condition. In addition, their children may not have the opportunities to enter higher education due to their inability to afford expensive tuition fees. Then, are the regular workers happy? Owing to the decrease in the number of regular workers, they have to undertake additional tasks and responsibilities. Therefore, there is always a high risk of sickness or stress caused by overwork. There are many nonstandard workers whose health was once affected due to overwork when they were regular workers. In addition, it becomes difficult for them to get other regular work.

Both regular workers and nonstandard workers suffer from serious anxiety about their uncertain future. From the Western point of view, the Japanese labor market continues to have gender barriers. Since the mechanism of division of labor is not well established, tasks and responsibilities are more likely to be lopsided. The Japanese government promotes the work-life balance policy in order to break through this situation. The Japanese, particularly women, tend to think that they must choose between working life or family life after marriage. If the division of labor is successful, working life becomes compatible with family life. Besides, the idea of work-sharing is generally introduced to reduce the risk of unemployment. However, the realization of these trials is very slow. Most labor unions in Japan are formed by regular workers, and they exclude nonstandard workers from their membership. Thus, the opinions of labor unions do not always represent the voices of unfortunate nonstandard workers. Further, some regular workers may think that work-sharing has no benefit for them, as it would lead to a decrease in their salary.

It is impossible for individuals to overcome such poor economic conditions. If the government neglects this situation, Japanese society may be further divided, and the maintenance of the social security system could face a crisis. It is only political leadership and the government that can effectively deal with this problem. They need to establish rules that would create incentives for work-sharing and that would prevent the nonstandard workers from facing unjust treatment. JI

I thank the Social Stratification and Social Mobility (SSM) 2005 Committee and the Japanese Life Course Panel Survey Committee for the use of their data. Wataru Nakazawa (Ph.D) is a lecturer in the Faculty of Sociology at Toyo University nakazawa_w@toyonet.toyo.ac.jp