Investment — Putting a Portfolio Together

By Chris Cleary

If you had put all your money into Nasdaq stocks in March 2000, you would have had 21.6% of it by October 2002. You would have 46.3% of it now.

The moral is simple and obvious: don’t put all your eggs in one basket. Everyone knows that. But I can assure you that going into 2000, an alarming number of people wanted their eggs in that one basket—the basket with the best recent returns. And despite the evidence of the following months, faith was retained in that basket until just about eight out of ten eggs were broken. It was an emotional time.

Early in the 1950s Harry Markowitz suggested that asset allocation accounts for approximately 90% of portfolio performance on a risk-adjusted basis, a figure that has been borne out repeatedly by subsequent studies, and, incidentally, earned him a Nobel Prize for Economics in 1990. This suggestion is called Modern Portfolio Theory. It holds that a diversified range of assets will produce not only more consistent, but also better returns over time than contending ways of running a portfolio, namely securities selection and market timing. It is in fact a staggering observation on Wall Street activity that the hundreds of millions of dollars spent annually on stock research and the timing of buys and sells don’t make that much difference to portfolio returns (although they do foster investor illusions and thus public enthusiasm to invest). Markowitz’s suggestion is that the area really worth concentrating on is asset allocation. In other words, the baskets.

The simplified and prevailing version of Modern Portfolio Theory is to have a blend of bonds and stocks, adjusting the relative percentages according to the desired risk profile of the portfolio in question (more bonds = less risk/ more stocks = more risk). This mix is called the ‘Traditional Portfolio’. It is easy to see how this works in periods when the economy is cyclical: when economic prospects are good, stocks rise in anticipation of higher future earnings; the economy heats up; the central bank raises rates to cool things down; economic prospects dip; bond prices rise in anticipation of lower inflation. So basically while bonds are strong, stocks are weak, and vice versa. However, the Traditional Portfolio is a limited basket set, and things do not always work out as planned. You can have falling bond prices and falling stock prices, as in the latter part of the 1970s—and, of course, rising stock and bond prices, as in the mid 1980s.

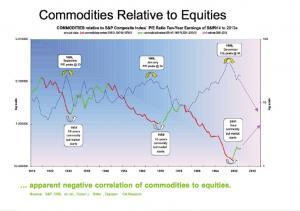

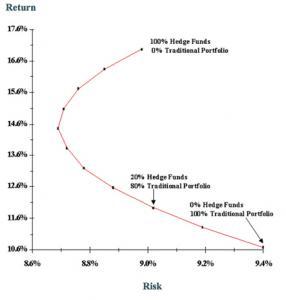

A rigorous application of Modern Portfolio Theory will distinguish among kinds of stocks (large cap/small cap; value/momentum; sector), kinds of bonds (high grade/high yield; sovereign/corporate), and both across currencies. This kind of asset allocation matrix makes for a much more thoroughly diversified and therefore durable and efficient portfolio. We can also add property into the mix, both as value (although property values do not always go up, as in the UK in the late 1980s) and as income. Then there are commodities—an interesting asset class indeed as they tend to rise and fall counter-cyclically to the broad stockmarket—although of course commodities stocks are powered by commodities prices. Finally, a modern asset class not available to Markowitz at the time is hedge funds, by which I mean disciplined alternative strategy funds that achieve returns in a wide variety of market conditions by hedging out risk. Time and again, it has been demonstrated that the risk/return profile of a traditional portfolio of stocks and bonds is enhanced by an admixture of hedge funds, extending the ‘efficient frontier’ of graphed returns leftwards and upwards.

What to do about this? The obvious is to make a wide range of investments. This is not intended as a facetious remark, as many people do not when they have adequate means; but for most of us who do not have the wherewithal to buy the implied list above in one go. It is important to make sure that each investment is of a different type, i.e. a different asset class to the last. However, it is also of interest that current regular savings vehicles offer a wide range of asset classes — various grades of bond funds; various nationalities, sectors and capitilization sizes of stock funds; property income funds; commodities funds; and hedge funds, which can be entered for as little as ¥20,000/month split up to ten ways. You can therefore start off a diversified portfolio from nothing, and furthermore enjoy the averaging effect along the way, as you are putting in the same amount every month. If prices of a fund fall, you buy more units of it, thus gaining an advantage over the static nature of lump-sum investing.

There are a number of such portfolios available from major life insurance companies, starting at ¥20,000 or US$150/month. This sum can be paid by credit card, which is a convenient and cheap method of making the monthly transfer—in fact after a few months most people do not notice the amount they pay at all, but are building up a diversified lump sum. The funds that you invest into are with some of the major investment house names, such as Merrill Lynch or Fidelity. The funds can be switched at any time for free within a universe of eighty or so such funds.

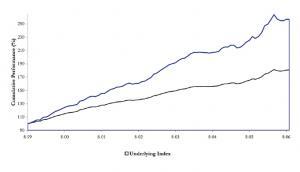

If the monthly route is not for you, however, there are also packages of diversified investments, participating in, say, one hundred futures markets and eighty fund managers, wrapped in a capital guarantee. The minimum for this kind of fund is less than ¥500,000 and has returned 285% over a nine-year period. For US$20,000 you can get a similar fund with a 120% guarantee. That’s a basket where the eggs are wrapped in cotton wool. JI

Further information can be obtained by contacting 03-5724-5100

Email: questions@bannerjapan.com

Web: www.bannerjapan.com

Chris Cleary is Director of Banner Japan K.K.