Failed Businesses in Japan

A study of how different companies have failed, and tips on how to succeed, in the Japanese market

By Greg Lane

With the Japanese government’s push to encourage foreign firms to set up in Japan, along with the enormous success of foreign companies from Goldman Sachs in financial services to LVMH in luxury brands, through to vacuum cleaner maker Dyson, it has become somewhat unfashionable to talk about their not so successful counterparts. However, the travails of the best and brightest of Western capitalism: Vodafone, Carrefour, Burger King, Pret a Manger, Boots, eBay and their many, many less illustrious cousins, indicates that there are some lessons that aren’t being learned.

Although the corporate spin doctors may cite a strategic re-alignment of resources, pressure in their home markets or forces beyond their control for their ‘spatial adjustment’ in departing these isles, the brutal truth is they made major mistakes. They all suffered from rather serious lapses of judgment, employed flawed strategies and demonstrated a lack of understanding in regards to both the dynamics of the market to which they had come, and the highly particular demands of the Japanese consumer. This article looks at three case studies of ‘getting it wrong’ in Japan before moving on to consider ways in which businesses can be more successful.

1. Red is for stop:

Vodafone Japan

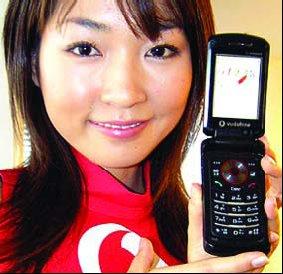

Autumn, 2004—Vodafone’s flagship store in Shibuya, the hottest shopping district in Tokyo. Young girls with over-glossed lips, whitish dyed blond hair and dark tans, young couples and the odd otaku (Japanese nerd) wander in and out of the store picking up the handsets, flipping the clamshells open with a flick of the wrist, feeling them for weight and running the tips of their fingers over the tactile keys. The handsets on display signaled Vodafone Japan’s final integration into the global 3G strategy. A young couple enter the store and begin to browse through the phones. The girl picks up one of the older 2G handsets and turns it over, returning it to its plastic cradle with little reaction. Then, she reaches for the Sony Ericsson 802SE. Just with the solid weight of the handset she screws up her face. Flipping it open elicits a look of disgust, “Yada kore!” she exclaims to her rather passive boyfriend. Simply translated: “Yuck!” Vodafone had launched a full range of mobiles with features and styling almost a generation behind those available from the other major carriers. Like some kind of modern day museum piece, one of the phones even had a monochrome display—something not seen on a Japanese mobile since the year 2001.

Despite some initial success largely due to initiatives by J-phone, the brand Vodafone acquired in 2001, Vodafone’s experience in Japan was painful—at least until March 2006 when it was able to unload a 97.7% share of its Japan operations to SoftBank for a very generous JPY1.8 trillion. The long sigh of relief emanating from Vodafone Japan’s HQ was audible.

Vodafone Japan: never lived up to its own hype

Vodafone Japan: never lived up to its own hype

With the switch from J-phone’s blue to Vodafone’s red livery on October 1 2003, the joke amongst Japanese staff was that things had gone from ‘go’ to ‘stop.’ (In Japanese a green traffic light is referred to as blue.) Vodafone Japan’s missteps are most clearly captured in their 3G strategy. Despite the fact Jphone had already been trailing competitors AU and DoCoMo in rolling out their 3G network, Vodafone had not increased investment to catch up. The first handset to be launched under the Vodafone name was the chunky Sanyo V801SA. The underwhelming response to this and subsequent handsets, as well as a delay in launching accompanying 3G services led the global marketing big-wigs to the stunningly bright idea of tying the re-launch of their Japan 3G offering into their global 3G launch—culminating in the embarrassing and hugely damaging debacle detailed above.

Unfortunately for Vodafone Japan, it wasn’t just a matter of correcting a marketing error (albeit a pretty major one). Even when the ‘global standard’ handsets had been relegated to the bargain bins, to be replaced by Sharp and Toshiba handsets that better suited the Japanese market, the lack of investment in their 3G infrastructure was still glaringly obvious. Although Vodafone finally moved with speed to rectify the problem, users, even in major metropolitan areas, were often left with frustratingly unusable handsets.

In the three year period from the change to the Vodafone brand, to its sale to SoftBank, Vodafone Japan had grown its subscriber base by an anemic 4.2% during a period in which the market had grown by more than 16%. Most tellingly, at the time of their exit, Vodafone had captured a measly 6.3% of the high value 3G market.

2. Bigger than big in Japan:

Carrefour

The reporter let out a loud (fake) gasp. As rehearsed, a young employee on roller blades glided towards the reporter through aisles wide enough to drive an SUV down, coming to a skidding halt right beside the camera. Outside, helicopters buzzed around the giant shopping complex. Hundreds of cars queued up along the unusually spacious (for Japan) streets of Makuhari—a modern, planned city of wide boulevards located roughly midway between Narita Airport and central Tokyo—all waiting for the doors to open on Japan’s first Carrefour supermarket. A hypermarket so massive that its meat department alone was bigger than the average neighborhood supermarket.

Despite this hugely positive reception, within a year, Carrefour’s problems were already clearly apparent—it had a harder time finding suitable store sites than it had anticipated. Planned stores in Fujisawa and Nagoya were shelved. To add to their troubles, Carrefour started to feature in the morning news bulletins for the wrong reasons. In a country where the media is intensely interested in food safety, minor scandals such as the mislabeling of low grade Japanese pork as higher grade American product, and being caught selling ham after its use by date, were starting to scratch at Carrefour’s sophisticated French veneer.

In the end, sliding consumer confidence and the trouble of finding new locations meant Carrefour was unable to implement its business model. Their strategy depended on a rapid expansion in sales to cover capital costs and deliver economies of scale across its logistics network. With the tight margins of fast moving retail, Carrefour also needed the bargaining power with which to gain concessions from Japanese suppliers. Rather than approach the second biggest retail market in the world with a long term, strategic approach, Carrefour had attempted an incredibly risky retail equivalent of a blitzkrieg—with woefully insufficient information on the market and no plan B!

Although the Carrefour logo still graces seven hypermarkets in the Kanto and Kansai regions of Japan, they are all owned and run under license by Japan’s largest supermarket operator Aeon Marche.

3. Don’t be late:

eBay

Among the darlings of the internet boom of the late ’90s, eBay was almost unique. Unlike the eternally promising (at the time) Yahoo! Or Amazon, from eBay’s foundation in 1995 they were profitable. With a good global track record and with little public fanfare, eBay launched its Japanese site on February 28, 2000. Two years later when eBay pulled the plug on its Japanese operations, they reportedly held an insignificant 3% of the Japanese online auction market. EBay had been pulverized by Yahoo! Japan Auctions— launched to immediate and enormous success approximately six months prior to eBay’s entry. Whereas eBay charged commissions of up to 5% and required acutely risk-averse Japanese users to submit credit card information on signup, Yahoo! Japan Auctions charged no commissions and met the particular needs of Japanese users to a tee.

Paul Anders Schwamm, a Tokyo based entrepreneur with 16 years experience of assisting and managing Western enterprises in Japan sees the failure of eBay as a classic case study on how not to launch a business in Japan. “It seems that they did just about everything wrong” he explains. Schwamm identifies three key mistakes that eBay committed. “Firstly, they hired the wrong person as country manager. Secondly, they tried to force Japanese consumers to fit the company’s American-centric service model, rather than modifying the company’s service model to meet local market needs. Thirdly, they did something that American companies are notorious for—and something that I think cost them dearly—namely, they made grandiose announcements about their entry into the Japanese market, well before they had a localized product ready to launch in Japan.”

While missing the first mover advantage was perhaps eBay’s single biggest blunder, the subsequent rise of Rakuten Auctions as a competitor to Yahoo! Japan Auctions, as well as the lack of traction in Japan for eBay products Paypal and Skype, suggests that their final mistake may have been throwing in the towel too early.

We’re here for a good time not for a long time

“They have to take a longer view,” laments Ray Tsuchiyama a veteran of 20 years in the IT and telecoms industries in Japan and China, former manager of MIT’s Asia office and currently Head of Emerging Markets at AOL Mobile. Tsuchiyama thinks comparing the experience of the most successful Japanese companies provides an interesting contrast to some of the flash in the pan foreign company entries into Japan. “The Japanese, when they went out to America and so forth, they sold lousy products that nobody would buy. They learned and learned and learned and incrementally improved their products until now they’re preferred” explains Tsuchiyama.

Schwamm too sees this as a key shortcoming of foreign companies who come to Japan. “Companies that have hundreds of staff and have invested tens or hundreds of millions of dollars in their home country operations over ten years or more with many setbacks before ever becoming successful or profitable, will often expect a newly opened Japan office with a relatively small local team, and often with an inadequate level of home office support, to successfully launch products, make significant sales, and reach profitability all within unrealistically short time frames.”

Another key area for mistakes identified by both Tsuchiyama and Schwamm is in human resources. First, in the selection of country manager, both think the issue of language is overplayed. Explains Schwamm, “If companies want a bilingual person to facilitate communication with the home office, they can hire a bilingual executive assistant, translator, or interpreter for a fraction of what it costs to hire a country manager. Making language skills a key recruiting criterion severely reduces the pool of potential candidates. Rather than focus on language skills, foreign companies should care about the truly important things, like a country manager’s strategic thinking ability, his track record managing comparable businesses, industry knowledge, and, ultimately, whether or not he can successfully build and motivate a local team, introduce new products, and gain market share in a highly competitive market.”

Aside from choosing the right head honcho, it seems foreign companies have much to learn from domestic business. According to Tsuchiyama, “The HR organization in a leading Japanese company is at the top of the hierarchy. In the US, it’s at the bottom. It has to be empowered, it must have very top people, it must engage with people—it’s not about recruiting—I think organization development is very, very complex and requires a higher level of people than are in many HR departments in gaishikei (foreign firms) right now.” In this area Schwamm sees a failure to utilize the talents of Japan based foreigners to smooth interactions between head office and Japan-based operations. “There are quite a few foreigners who have many years of valuable experience managing in Japan, as well as relevant industry knowledge and connections, who can help foreign companies successfully navigate Japan market entry.”

Back from the dead

Recent returns by a couple of big global brands such as Burger King suggest the route for those companies who exit Japan may not be a one-way street. Another company that has generated almost fanatical excitement since its return is Swedish furniture giant IKEA.

IKEA: back in Japan after learning the hard way

IKEA: back in Japan after learning the hard way

IKEA first came to Japan in the mid 1970s as part of an early wave of expansion in Asia. Following a long struggle, IKEA pulled out of Japan in 1986. Then, after developing into the global phenomenon that saw virtual riots among eager customers at the opening of new stores around the world in the ’90s and early 2000s, IKEA returned to reopen a giant store on the outskirts of Tokyo in 2006.

Lars Petersson, CEO of IKEA’s Japan operations, sees the IKEA of today as a quite different company to that which tried and failed in the Japanese market more than 20 years ago. As a result of IKEA’s first foray into Japan, Petersson says, “We learned that there is the humbleness of understanding. It’s not [good enough] just to land here and hope that everything is going to work. You need to have everything in place—the whole supply chain, the well trained coworkers and an organization that can actually expand and grow.” Petersson also believes IKEA’s success since its return is because of the special care they’ve taken to get to know their customers. “We do thorough research of actually what is the need...how do people live in their homes?” continues Petersson. Despite IKEA’s troubles on its first excursion to Japan, Petersson places little credence in the idea that Japan is more difficult for foreign companies to set up shop than in other markets, such as North America or Europe. He feels that failures have been exaggerated and that may have deterred some global brands from entering the Japanese market. “Yes, there are difficulties in Japan but there are difficulties in Russia, there are difficulties in Poland...” explains Petersson.

Petersson ends with some advice pertinent to any international company looking to avoid the fate of some of the illustrious firms mentioned thus far, “I think to come to Japan (or Poland) thinking you are in just another country is the start of the failure because there are a lot of local things you need to understand. You need to have local people employed right from the start, at a high level, that understand what this country is all about.”

Greg Lane is co-founder of fusionbureau design studio.

Email: greg@fusionbureau.com

Web: www.fusionbureau.com