US Election: The Waiting Game

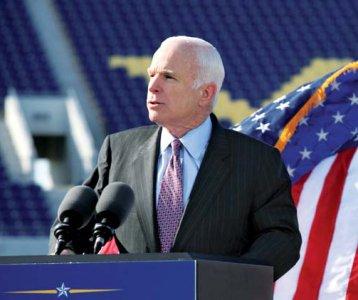

Republican presidential candidate John McCain stands with wife Cindy.

Republican presidential candidate John McCain stands with wife Cindy.

By Tobias Harris

Where does the next American president see Japan’s place in Asia?

Every four years, as Americans prepare to elect a president, Japanese elites struggle to divine the ramifications of the US presidential election upon the US-Japan relationship. They parse every word written or spoken by the presidential candidates and their advisers in search of clues for how the incoming administration will approach Japan.

Will it push for greater security cooperation? Will it pressure Japan on trade and investment? Will it “pass” Japan and prioritize the US relationship with China?

One wonders why Japanese elites worry so much. By any measure, after the economic turbulence of the early 1990s, the US-Japan relationship has been uniquely free of strife. Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) commissions an annual survey by Gallup on the “US Image of Japan” that measures public and opinion leader sentiment about Japan. Since 1993, when Gallup began surveying opinion leaders, the percentage of opinion leader respondents who view Japan as a “dependable ally” has never fallen below 74 percent, and since 1995 the lowest has been 85 percent. The general public has been slightly less enthusiastic, but during the same period approximately two-thirds of respondents from the general public view Japan as a dependable ally. Over the same period, the percentage of both elite and general public respondents, who judge the relationship to be excellent or good, has remained steady. In the mid-eighties it was among elites; in the mid-sixties, among the US public at large. By every measure used by MOFA, there is strong support among the American people and even stronger support among their leaders for an enduring US-Japan partnership.

Indeed, the foundation is such that the US-Japan relationship is one of the few foreign policy issues on which there is a broad consensus between the Republican and Democratic parties. Both parties have, with the partial exception of the early 1990s, embraced the motto of former US Ambassador to Japan Michael Mansfield (a Democrat serving under a Republican president). Mansfield called the US-Japan relationship the “most important bilateral relationship in the world, bar none.” Both Democratic and Republican administrations have viewed the US-Japan alliance as the cornerstone of US Asia policy and have sought to strengthen the security partnership. And yet, Japanese elites continue to fret at election time about whether the election will have significant consequences for the US-Japan alliance. Perhaps they have good reason to worry, despite the positive trends in the relationship.

The biggest factor is the fear of abandonment by the US. Is there a danger that one of the contenders, if elected, will reorient US foreign policy away from Japan, whether in pursuit of isolationism or cooperation with other countries, most notably China? The 1971 Nixon shocks are the central cautionary tale of modern Japanese foreign policy, reminding Japanese that in the face of troubles at home and abroad, US presidents could disregard the relationship and turn away from Japan. Both former President Bill Clinton and President George W. Bush have revived latent fears that the US will turn to China to solve regional and global problems—Clinton by coining the term “Japan-passing,” late in his administration (an episode which was inflated out of proportion to the offense); Bush most notably by working closely with China and shifting away from Japan’s position on North Korea.

Obama states he would tackle problems in Asia looking at solutions rather than strategic partnerships.

Obama states he would tackle problems in Asia looking at solutions rather than strategic partnerships.

Accordingly, it is not surprising that given the association of her husband with “Japan-passing,” Japanese elites frequently cited Senator Hillary Clinton’s essay in Foreign Affairs—“Our relationship with China will be the most important bilateral relationship in the world in this century”—as a sign that a Hillary Clinton administration would break with the bipartisan consensus and subordinate the US-Japan alliance to the US relationship with China. But with the defeat of Senator Clinton in the Democratic primaries by Senator Barack Obama, can Japan breathe a sigh of relief? Do Japanese elites have nothing to fear from either Senator Obama or his Republican rival, Senator John McCain?

Superficially, both campaigns are committed to the bipartisan consensus. Both candidates have accomplished advisers on Japan policy. Both campaigns have published op-eds on Japan policy in Japanese newspapers: Senator McCain co-authored an op-ed with Senator Joseph Lieberman in the Yomiuri Shimbun, Obama advisers Joseph Nye and Richard Danzig wrote a piece for the Asahi Shimbun. Senator Obama went so far as to issue a statement in response to former Prime Minister Yasuo Fukuda’s resignation, thanking him “for his leadership on climate change and the support that Japan’s Self Defense Forces have offered the US operation in Afghanistan.”

As for the policy positions of the two campaigns, both campaigns have argued that the US-Japan relationship rests on shared interests and shared values. Both see the alliance as central to the US position in Asia; as Nye and Danzig wrote, “Close cooperation with Japan is the starting point for US policy and interests in Asia.” Both seek a broader bilateral agenda and a more active Japan. But the similarities end there.

While there is a paucity of evidence on the views of the two candidates on Japan, the aforementioned opinion pieces suggest a genuine difference in how they view the alliance, rooted in their differing approaches to foreign policy more broadly. The difference can be characterized thusly.

McCain’s approach is partner-oriented: he acknowledges the problems, but is more interested in the partners (and their values) than the problems. In short, get the partners right and the solutions will follow. This is the implication of McCain’s emphasis on cooperation among democracies—his call for a global “League of Democracies.” A McCain administration would likely try to revive the Asian league of democracies comprised of the US, Japan, Australia, and India (but mysteriously excluding South Korea) that was shelved with the demise of the Abe cabinet. Cooperation among democracies does not forestall cooperation with China and other “unsavory” regimes in the region, but it is clear that McCain’s commitment will be to strengthening cooperation among democracies on the Asian littoral, starting with Japan. But shared values will not just be the glue uniting the US and its allies in the region: they will serve as the basis for a regional policy that sees promoting democracy as the critical task for the US in the Asia-Pacific. And for McCain, a strong alliance is a prerequisite for working with China. The question is how China will react to a McCain administration’s efforts to strengthen cooperation among the region’s democracies. It seems unlikely that China will passively accept such an initiative, seeing as how it could reasonably conclude that this new bloc is aimed at encircling and containing China.

By contrast, Obama’s approach is problem- oriented: he sees foreign policy problems that need to be solved, and is more interested in seeing them solved than in which countries the US cooperates with to solve them. For Obama, the task is to get the region right. Nye and Danzig wrote of embedding the US-Japan alliance at the center of a new bloc of democracies but as a key to the construction of a new regional framework that presumably doesn’t discriminate between democracies and non-democracies. “Without reducing the US-Japan alliance’s central role as the ‘foundation for regional stability,’ ” they write, “It is possible to create new frameworks and dialogues.” At the same time, Obama himself has suggested that he will “get tough” on trade with South Korea and Japan, not to mention China. But protectionism, while satisfying to voters at home, could have disastrous consequences for US efforts to lead in Asia.

But we have only the slightest impressions of how a McCain or an Obama administration will conduct US Asia policy. Despite East Asia’s growing importance, it does not figure in US presidential elections —unless it is being used as a scapegoat for US economic problems. Asia policy will likely be reactive, rather than creative, and as a result the differences between the Obama and McCain campaigns may ultimately be unimportant.

With East Asia in the midst of structural changes that will alter the US role in the region, the next administration will find itself with a limited range of options for US Asia policy. As the Bush administration has already learned, on a number of issues —most notably management of the Korean Peninsula— the US has few alternatives to working with China. Moreover, China’s growth has enmeshed all US allies in the region: the hub-and-spoke system that has defined the US-led alliance system in Asia now has a parallel system for economics, with China the trade-and-investment hub for the region. While US partners do not want the country to abandon its regional security role, they are also not eager to alienate China. Even Japan, commonly viewed as having the most to lose from China’s rise, has sought to build a constructive relationship with China that will reinforce their dense economic ties.

McCain’s partner-based approach to foreign policy envisages Japan as part of a “League of Democracies.”

McCain’s partner-based approach to foreign policy envisages Japan as part of a “League of Democracies.”

In short, the next US administration will find itself constrained both by its allies’ needs for constructive ties with China —and its own need for China as an economic partner and a partner in addressing regional and global issues. This will necessarily entail a shift away from the US-Japan relationship, even as both candidates insist upon the centrality of Japan to US Asia policy. China’s gravitational pull is only one reason for the shift. Equally important is Japan’s turn inward. As Japan’s government has struggled to fix mounting domestic problems, its ability to act as a regional leader has diminished, making it a less reliable partner for the US in addressing the region’s transnational problems.

The next president, then, will find himself looking to China as he seeks to address Asian challenges. Tokyo will still be consulted and Washington will still commit energy to the security relationship and the US presence in Japan, but in political cooperation, in the diplomacy that will shape the future of the region, the next administration will likely continue to bypass Tokyo and treat Beijing as the most important partner for the US in Asia. Even under a President McCain, the values purportedly shared by Washington and Tokyo will likely give way to the interests shared by Washington and Beijing.

How should Japan respond to the ongoing US shift? Developing its own ties with China is one response. But ties with China are not enough. Japan will also have to forge deeper ties with other powers in the region, particularly those “middle powers” that, like Japan, enjoy security partnerships with the US and dense economic links with China. Tokyo will have to become less interested in pleasing Washington than in working with other countries in the region to keep the US and China from becoming either too antagonistic, carrying the risk of war that could engulf the region, or too cooperative, which could result in the US and China imposing their will on the region.JI