Real Estate -- REITs

By Hugh Ashton

Some light at the end of the tunnel?

The Japanese real estate and property developer worlds, like so much of the financial world, appear to be in a state of crisis. Residential property developers, builders, etc. appear to be dropping like flies—almost every day seems to bring news of another failure in this area.

For a long time, Japanese real estate, particularly in the metropolitan areas, had been regarded as a guaranteed moneyspinner, especially at the end of 2003, according to Mark Pink of TMJ NetSearch, a close observer of, and service provider to, the sector, where the banks were being pressured to prop up this part of the economy at the bottom of the current business cycle. The boom continued until about February 2006, when the “Livedoor shock” hit the Japanese markets, closely followed by the “Murakami shock,” which effectively put an end to any hope of corporate reform in Japan. Raising capital for Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) became a problem as the equity value folded, and wiser investors saw the downturn as a longer-term phenomenon than had previously been thought.

Although as late as November 2008, some Japanese REITs were predicting increased profits based on rent readjustments, the debt-to-equity ratios of these entities belied the optimism. Practices such as REITs paying over market price for properties purchased from allied management companies, resulting in lower yields, has left investors wondering in whose interests the REITs are really acting.

Such practices as offering “rent holidays” to existing tenants in lieu of rent reduction to disguise the reduced annual income by maintaining a notionally continuous level of monthly income also militate against a true valuation if investigation brings them to light.

In addition, the financing for some past commercial projects was too expensive given current expectations of rental prices, which are below that needed to recoup the costs of financing. This has led to largely unoccupied buildings—one example being close to Tokyo Station, where the Shangri- La Hotel has been waiting for other tenants to occupy the building before opening for business.

Pink sees hope in what he terms “creative destruction”—the revival of distressed REITs that made past false assumptions regarding the type of property and the financial assumptions underlying the investments. Although the regulators are working to try to redress the situation, for example by revising tax laws to allow troubled REITs to be taken over without severe penalties accruing to the purchaser, in Pink’s view, this is too little, too late. The overly complex nature of Japanese REITs, where separate companies typically manage the property owned by the trust as mentioned above (as compared to the foreign model, where the same company owns and manages properties) also means that simple solutions are hard to come by. Even so, one possible example of this revitalization is the New City Residence Investment Corp. bankruptcy, declared in October 2008. It formed the first major domestic post-Lehman event of its kind and served as a trigger for foreign investors who had been circling around the distressed Japanese market for some time. They were evaluating possible offerings, not with the aim of making a deal there and then, but probing for weaknesses, and waiting for the event that would allow them to move in.

New City’s failure provided such an opportunity. At the time of writing, it was reported that some special situation groups, operating on a “last in, first out” principle, have an interest in this distressed entity. These include the Goldman Sachs Group Inc., Oaktree Capital Management, and Lone Star (the original purchasers and owners of Tokyo Star Bank) as well as several domestic players. For a variety of reasons that need not be explained in detail here, distressed Japanese properties are much more attractive to such investors than Chinese or Indian, which are also suffering a slump.

Maybe the main poster child for foreign capital in real estate is domestic property developer Suncity Co., which, despite an expected 13 billion yen loss for calendar 2007, recently attracted up to 24 billion yen from a Singapore-based Chinese family investment company. The key to this success was the fact that Suncity’s Website featured information in both Chinese and English detailing the properties available. IPC, the Singaporean investment firm, had previously concentrated on other areas, but seeing the Website in a language they could understand and examining the Japanese real estate market forced a change in their investment thinking, according to Tadao Nakai, who came from a hedge fund to assist Suncity. Naturally, no-one invests such a large sum of money sight unseen, and Nakai adds that the principals of IPC visited Japan several times to kick the metaphorical tires, to ensure their investment was well placed.

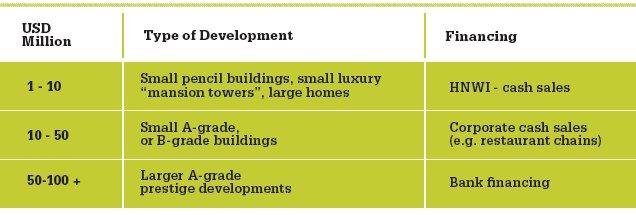

Of course, such family-based investment is not available for all building projects (see chart, left), and some projects are not desirable investments in any case (Pink points to a two-year-old, four-story commercial “pencil building” near his office which is now being offered at about 55 percent of its original asking price—and the price is still falling). For REITs, the current lack of personal affluence means that residential properties are unlikely to rise in value, with any REIT that has invested in such property no longer able to rely on a Japanese bank for refinancing. Such REITs are prime targets for investment from overseas, especially as Japanese owners are more likely to postpone the sale of their distressed properties than overseas owners in the same position, thereby depressing the value further.

One factor that has not been mentioned so far in this article is the influence of what are delicately termed “anti-social forces.” With known ties between such underworld organizations and the real estate and construction businesses (building standards scandals have depressed the pre-sales of residential products, for example), as well as the pervasive nature of these connections throughout the Japanese establishment, it is hard to imagine that a truly open and transparent real estate market will ever appear in Japan unless a massive house cleaning at all levels is carried out.

However, if proper due diligence is performed, there does seem to be an opportunity for patient overseas investors to purchase some of the more recent properties, both commercial and residential, which currently lack tenants, and are therefore available at bargain basement prices. A few years of waiting should see the investment recoup itself. JI