Economic Bondage

Back to Contents of Issue: August 2002

|

|

|

|

by Sumie Kawakami |

|

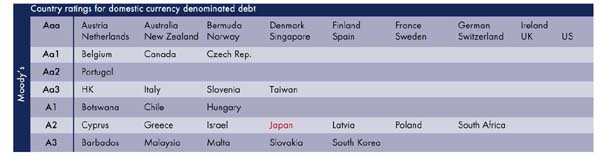

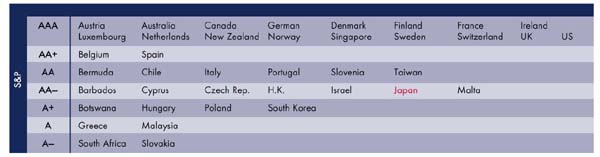

THERE WAS A TIME -- not long ago -- when Japanese government bonds were held in the highest esteem. Standard & Poor's, Moody's Investor Service and others gave the JGBs triple-A ratings or the equivalent as recently as a couple of years ago. But those days seem like ancient history now; instead today Japan and its bonds are ranked several notches lower by major Western rating agencies. This angers the Ministry of Finance no end. Government officials argue that rating Botswana higher than Japan is absurd. Almost half of that African country's citizens lived below the poverty line in 2000, according to the CIA World Fact Book. How could Japan, the world's second largest economy and its greatest saver bar none, be put into the same group? And while we're being diplomatically incorrect, how could it be ranked the same as Poland, Cyprus, Israel or the Czech Republic? Is this just another Western conspiracy to push the yellow man around? Or, as the ratings agencies argue, is the government a debt junkie, unable and unwilling to kick a destructive habit? THERE WAS A TIME -- not long ago -- when Japanese government bonds were held in the highest esteem. Standard & Poor's, Moody's Investor Service and others gave the JGBs triple-A ratings or the equivalent as recently as a couple of years ago. But those days seem like ancient history now; instead today Japan and its bonds are ranked several notches lower by major Western rating agencies. This angers the Ministry of Finance no end. Government officials argue that rating Botswana higher than Japan is absurd. Almost half of that African country's citizens lived below the poverty line in 2000, according to the CIA World Fact Book. How could Japan, the world's second largest economy and its greatest saver bar none, be put into the same group? And while we're being diplomatically incorrect, how could it be ranked the same as Poland, Cyprus, Israel or the Czech Republic? Is this just another Western conspiracy to push the yellow man around? Or, as the ratings agencies argue, is the government a debt junkie, unable and unwilling to kick a destructive habit?No matter how hard they try to hide it, they can't: Government officials are embarrassed by the nation's falling sovereign rating. The most recent downgrade by Moody's Investor Service in late May lowered Japan's yen-denominated government bond rating by two notches to A2, lower than any other major industrialized nation. Upon the announcement by Moody's, chief cabinet secretary Yasuo Fukuda openly expressed his disgust. He said the rating doesn't "properly reflect our country's economic power" and that the agency only saw "the trees without seeing the forest." Economy, Trade and Industry Minister Takeo Hiranuma showed his exasperation by asking rhetorically how Japan could be ranked lower than Botswana, a country where, in his words, "half the people have AIDS." (Hiranuma later apologized for the comment.) Finance Minister Masajuro Shiokawa told the press, "Even with the downgrade, the yen is appreciatingc Markets don't take Moody's into account." Oh, but they do -- and the government knows it. Moody's downgrade was a slap in the face to Japan's financial authorities as it came amid a battle between the Ministry of Finance and foreign credit-rating agencies. Even prior to Moody's downgrade, MOF had sent out open letters to rating agencies asking them to clarify their sovereign ratings. MOF's actions came after S&P downgraded its foreign and local currency sovereign ratings in mid-April for the third time since February 2001.  The ministry's letters were sent to all of the three foreign rating agencies authorized by the Financial Services Agency (FSA) -- Moody's, S&P and Fitch Ratings. Since the wake of Japan's financial crisis in the late 1990s, these agencies have been cutting their Japanese credit ratings, while their Japanese counterparts, Rating Investment Information (R&I) and Japan Credit Rating Agency (JCR), have kept Japan's ratings at triple A.

The ministry's letters were sent to all of the three foreign rating agencies authorized by the Financial Services Agency (FSA) -- Moody's, S&P and Fitch Ratings. Since the wake of Japan's financial crisis in the late 1990s, these agencies have been cutting their Japanese credit ratings, while their Japanese counterparts, Rating Investment Information (R&I) and Japan Credit Rating Agency (JCR), have kept Japan's ratings at triple A.Why the discrepancy between East and West? While each Western agency gives slightly different reasoning for its downgrades, they agree that Japan's fiscal debt is out of control and the government seems unable to correct the situation. Japanese ratings experts and government officials tend to stress the fact that the government debt is 95 percent Japanese owned and that the country has massive foreign reserves and personal savings. But bureaucrats and analysts alike are clearly concerned with the fiscal health of the government. "We might be bankrupt in 10 years," Hiromitsu Ishii, head of the government's tax commission, told the Financial Times in June. "Rate cuts have been done in the past. We need to broaden the tax base and it means a tax increase -- absolutely."  S&P argued in its April report that the main reason for its latest downgrade to AA-, or double A minus, was the delay in structural reforms. "A double A minus rating is still a very strong rating," points out Mike Petit, managing director and chief credit officer for the Asia Pacific region at S&P. "The risk of default is only fractionally higher than the triple As. But the risk of default is not static; it's on a continuum, and Japan has some very negative elements that increase its risk."

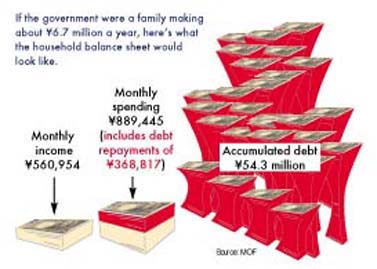

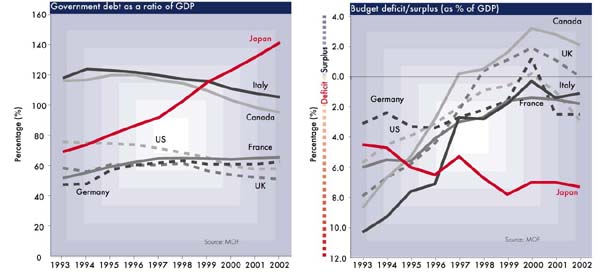

S&P argued in its April report that the main reason for its latest downgrade to AA-, or double A minus, was the delay in structural reforms. "A double A minus rating is still a very strong rating," points out Mike Petit, managing director and chief credit officer for the Asia Pacific region at S&P. "The risk of default is only fractionally higher than the triple As. But the risk of default is not static; it's on a continuum, and Japan has some very negative elements that increase its risk."Those negative elements include government debt that S&P sees soaring to 200 percent of GDP "later in the decade" if left unchecked, Petit says, and that is a far higher debt ratio than anywhere else in the industrialized world. Everyone agrees that the massive government debt should be contained, but is it really fair to rank Japan lower than countries it gives aid to? That's what happened with the most recent Moody's downgrade of Japan's JGB local currency rating. Japan found itself rated lower than Chile, which received $417 million in aid from Japan in 1999, and Botswana, which received $122 million, according to the Official Development Aid White Paper. Moody's responds: "Japan's general government indebtedness, however measured, will approach levels unprecedented in the postwar era in the developed world, and c Japan will be entering uncharted territory." According to an OECD estimate, Japan's government debt as a percentage of GDP in 2002 is estimated to be as high as 141.5 percent, compared with 58 percent in the US, 50.9 percent in the UK, and 105.2 in Italy (see chart, page 28). Moody's argues that countries like Botswana or Estonia may face problems because of their lower level of economic development, but they have very little government debt (about 10 percent of GDP), therefore their credit ratings "in the 'A' range are appropriate."   Western ratings agencies are essentially saying that the government's inability to keep a lid on the debt is slowly strangling the economy. They tend to agree, too, that the cumulative debt shows no signs of subsiding -- rather it's likely to keep rapidly rising. So far, Japan has no problem selling bonds despite its dangerously high debt. Institutional investors -- pension funds and insurance companies alike -- are still big bond holders. "Investors are not doing charity work," says a bond trader. "They buy JGBs because risk-return related to bonds is still not too bad." But the government has already taken a couple of steps to reach individual investors. In the summer bonus season the government launched an ad campaign with supermodel Norika Fujiwara hawking government bonds. It spent JPY476 million on the campaign, plastering posters around town with a picture of Fujiwara looking off into the distance. The text reads: "A safe investment starting from JPY50,000. I've got a feeling government bonds may be good." A ministry official, when asked if the large advertising budget for JGBs was in response to Japan's plunging credit ratings, simply answered, "We've got a good response. That's all." The government will also lower the smallest lot an investor can buy from JPY50,000 to JPY10,000 as of January 2003. To date, only 2.5 percent of Japan's bonds are bought by individual investors. "I was surprised by the move," S&P's Petit says. "There has been no indication of the government having difficulty in selling JGBs. I think it's a smart, anticipatory move to broaden their investment base." Even MOF admits Japan has a serious problem. The ministry says the debt-to-GDP ratio will reach 139.6 percent by the end of fiscal 2002, with accumulated debt reaching JPY693 trillion (Japan's GDP is JPY496.2 trillion). In the same fiscal year, bond-related expenditures are expected to equal JPY16.7 trillion (20 percent of the total), including interest payments of JPY9.6 trillion (11.8 percent of the total). That means Japan's annual debt servicing equals more than three-quarters the total market capitalization of all companies listed on Nasdaq Japan, Jasdaq and Mothers. Those markets, heavily weighted with venture businesses, had a market cap of JPY12.26 trillion as of May 2002. MOF makes the government debt a little easier to grasp on its Web site through the example of a household with an annual income of JPY6.73 million. If it had the same percentage of debt as the government, it would have to pay JPY180,000 out of its monthly income of JPY560,000 for debt servicing. An additional JPY190,000 would be sent to support the family's parents (in the government's case, this is payments to local governments). That leaves JPY190,000 to spend. But with monthly expenditures of about JPY520,000, the family has to borrow JPY330,000 each month to make ends meet, and it has already racked up a JPY54 million debt. That's not a happy household. Even so, some analysts found Moody's last downgrade ill-timed. "It would have had a bigger impact had it happened earlier this year. But the Japanese economy has been showing signs of recovery nowadays," says Hajime Takata, chief strategist at Mizuho Securities. The downgrade didn't seem right," says a senior strategist at a Japanese bank. "I'm personally not convinced and neither was the market c The fact that Japan has some problems in fundamentals in the long-term is true, but there is no additional reason (for a downgrade) now. It doesn't mean that fiscal factors, as well as fundamentals, are worsening. Recent economic indicators show that Japan is back on a recovery track." Critics of Moody's latest cut say it has led to the strange situation where some Japanese corporations have higher ratings than the nation. "It is understandable for some global companies like Toyota to have better ratings as they could arguably survive even if Japan went into default," says Takata. "But, what about more domestically oriented companies?" Currently, Moody's gives 77 Bank and Shizuoka Bank higher rankings than Japan. One of MOF's arguments against the series of downgrades is that Japan has a strong external balance with a high level of foreign reserves. "Unlike an emerging market economy whose domestic currency bond defaulted recently, Japan has a strong external balance," MOF says in a press release. Besides, it argues that 95 percent of JGBs are held by Japanese people who have an extremely high level of personal savings. "While the deficit of the general government was JPY32 trillion, the excess savings of the private sector stood at JPY42 trillion in 2001," MOF says. Considering that the current account surplus will continue for some time, "the risk of capital flight is small," it says. Be that as it may, is the government unfairly draining the economy of its strength? Some analysts think so. "Japan has no difficulty in selling JGBs," Petit of S& P says. "Some people say that is why it should have a triple A rating. But the other explanation is that c in a weak economy with a deflationary environment and increasing bankruptcies, JGBs are an attractive alternative. "It's a typical phenomenon in weakening sovereigns," Petit adds. "The banking sector reduces loans to the corporate sector, but they still need to place deposits somewhere. So they go to sovereign bonds." And what if individual investors listen to Ms. Fujiwara and buy more bonds? Petit says second-tier banks, credit cooperatives and regional banks will suffer as people worried about the health of these banks decide to make safer investments. In other words, the government would be siphoning off funds from banks struggling to survive. Moody's lowered Japan's yen-denominated debt rating this spring, but left its foreign currency denominated rating at Aa1, four notches higher than the yen-denominated rating. It's an odd combination of ratings because in theory, if a country cannot repay its debt to itself, it would be difficult for the country to pay back external debt. Moody's says the ratings are based on Japan's very strong external position. Besides, since savers will continue to be wary of foreign-currency-denominated investments, there will be a low risk of "capital flight, instability in the balance of payments and an uncontrolled depreciation of the currency," according to Moody's. What the rating agencies are taking issue with is not the fears over Japan's fundamental strength or its inability to repay foreign-currency-denominated debt, but the government's ability to manage public finance, says Koyo Ozeki, managing director at Merrill Lynch. Moody's decision to downgrade yen-denominated debt is "a signal by the foreign rating agencies of what they see as the divergence between Japan's fundamental economic strength and its government's inability to manage public finance," he says.  "Even with the Japanese stock market recovering and the forex market pushing up the value of the yen, these factors do not have any essential bearing on Japan's medium- to long-term risk," Ozeki says. And that long-term risk is in the hands of the government. But don't make a run on your local bank just yet. Moody's argues that Japan could sustain "substantially higher debt levels" by world standards, as household savings provide a high level of financial stability. And, when confronted with the alternatives, the government would chose "non-default options," such as the use of aggressive monetary expansion or a wealth tax. S&P also says that if Japan can sustain its "negative real interest rates," it may stabilize national debt levels. Also, the Bank of Japan is buying JPY1 trillion worth of JGBs every month. "The Bank of Japan is purchasing government debt directly, which is a form of increasing the money supply," Petit says. But S&P considers this to be the "least attractive" way for Japan to curb the trajectory of government debt. Some analysts argue that the ratings downgrades may have severe impact on the Japanese bond market in the longer run. Credit ratings are, in principle, merely the "opinion of a private company," says Takata of Mizuho Securities, but in reality "investment restrictions are based on such credit ratings; some investors (like pension funds) may not be able to buy bonds below a certain credit-rating level." Also, possible downgrades on financial institutions would further impede the flow of funds. "Even if the BOJ maintains its easy monetary policy there could be an unintentional tightening effect," Takata says. Japan's super-easy monetary policy was originally meant to speed up bad debt disposal and boost new borrowing by corporations. As it stands, neither is happening, or at least it is not happening as fast as the government had hoped for. And Japan's indebtedness is climbing to levels only a country like Japan can sustain. That's the message of the rating agencies. @ |

|

Note: The function "email this page" is currently not supported for this page.