The ability to procure raw materials and parts cheaply has always been a competitive weapon for major companies in Japan. Traditionally, large brand-name manufacturers have dictated terms and pricing to their keiretsu subcontractors, who in turn did the same with their job shops, and so on down the food chain.

But the drawback of such a multi-layered system is that over time its human managers become slow and lazy--as happened through the 80s and 90s.

Carlos Ghosn proved as much when one of the most decisive methods he used to fix Nissan was to slash the number of locked-in vendors and open up procurement to newcomers. Suddenly Nissan was able to cut its procurement costs by more than 11 percent, boosting its profits JPY331.1 billion ($3.01 billion). Today, Nissan is one of Japan's most efficient car manufacturers.

Still, a recent survey by the Electronic Commerce Promotion Council of Japan (ECOM) found that only 35 percent of technology-aware SMEs are actually using electronic procurement, and of those, just 10 percent of their transactions were done online. According to Ernst & Young, 40 percent of the average company's purchasing expenditure is on non-production items such as travel, office supplies and services. A 20 percent saving on such costs might amount to an average of 5 percent on costs overall and for a typical 100-person foreign firm in Japan is likely to amount to JPY26 million ($236,000) a year.

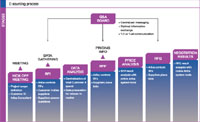

How procurement auctions work

The concept is simple: the buyer sets up an online or offline "marketplace" (a Web site or procurement office notice board), defines and posts the service or product to be procured, solicits and qualifies a range of existing and new vendors, then invites typically no more than five of those vendors to enter the auction to bid.

Auctions are usually conducted in a Dutch auction format, whereby the buyer sets the opening price and descending bids are made in rounds. Each round, the vendors respond with their best price, and everyone gets to see the lowest bid at the end of the round. Then, the next round is opened and the process repeated, often with just two vendors grinding away, until one of them gives up.

The winner then receives an order confirmation from the buyer, and the terms and conditions are not adjusted beyond those stated before the auction. To make such a system acceptable to Japanese vendors, the system has to be reliable, transparent and fair.

The rules are important, because not only do they keep things fair, they also spell out to vendors that things are changing and collusion between buyers and vendors is a thing of the past.

• Vendors participate by invitation only, therefore they must be pre-approved as being able to fulfill the requirements of the buyer. • Vendors participate by invitation only, therefore they must be pre-approved as being able to fulfill the requirements of the buyer.

• After issuance of the procurement request, vendors may not directly contact the buyer or their staff.

• Questions must be limited to no more than 10 items and must be clearly expressed.

• Responses to any particular question will be by email and will be open to all bidders, to maintain transparency.

• Everyone bids to the published buyer specification--no extras, variations, or deviations will be considered.

• Bidding will continue until there is no further price movement. The last bid is the winning bid.

• The winner of the auction may not further negotiate the terms and conditions (since this would obviously compromise the entire process).

The Chanel experience

In 2002, while Chanel was still in the planning stages for its new JPY24 billion ($218 million) Japan head office in Ginza, enterprising private consultant Blaise Anthony approached Chanel with the idea of starting up a procurement control function within the company for the purchase of interior architectural and construction services as well as office furniture. Anthony's proposition to Chanel's CEO Richard Collasse was simple: "Let me save you money by proactively managing your vendors and costs for this project."

Given the large sums of money involved, the proposition was both attractive and yet a potential risk. With deadlines on the building looming, what if vendors became offended by the initiative and refused to do business? Delays in the office opening would cost far more than the savings such a program might offer. Furthermore: What if the quest for better prices resulted in lower quality? This would be the antithesis of everything Chanel stood for.

To Collasse's credit, he decided to give Anthony a chance. In June 2003 Anthony was tasked with sourcing vendors for Chanel's multi-office relocation project.

One of his first innovations was an auction process for furniture and IT/cabling services. He made sure that the vendors were well informed of the company's intentions, and he produced the same level of RFP documentation that might be used in a traditional tender. He called the vendors in for two mass meetings: First to give them the RFP and to answer any preliminary questions, then a week later, to announce the vendors who had been selected and to actually conduct the auction.

"In the second meeting, I called the vendors in and announced 'You've all won the bid,' which of course surprised them given that their competitors were still in the same room. Then I explained. 'You have all passed the initial requirements for the project, our IT Manager has approved your bids, and consequently the only remaining aspect is the price. This will be decided by a fair and open auction which I hope you will all decide to attend.' "

This first auction, which was for a computer (LAN) cabling project, was conducted in a physical room, where the six vendors sat side-by-side. The focus of audience was a notice board, where Anthony's opening price was posted. Vendors were given bidding forms, and for each round they were asked to write down their best offer and submit it to a Chanel employee. The bids were then collated and the lowest one posted on the notice board, for all to see. The auction ran for several hours, and eventually the project was won by a vendor for a price 40% lower than the opening price.

The process was so successful that Anthony now asked to stay on and get involved in other procurement projects, conducting auctions on projects where cost savings were deemed large enough to be worth the effort.

One might expect that Japanese vendors would feel uncomfortable being in the same room and competing for the same business. However, according to Anthony, "as long as the rules were well-defined and unbiased, vendors rapidly got used to the methodology and the spirit of the auction that enabled them to determine their own destiny. Consequently, I believe that the philosophy of the auction procurement method is well accepted by our vendors and our procurement staff."

The technology

One of the problems with conducting auction-based procurement in Japan is the lack of inexpensive technology solutions.

We did find an alternative commercial solution, though, and that is the ASP arm of Ariba. Ariba, which announced a merger with online auctions provider FreeMarkets auctions back in January 2004, now offers its AribaLive service in Japan.

We spoke to Ariba's VP Asia Pacific, Leo Keeley. Keeley gave us some insight into the burgeoning market for online procurement. In conjunction with such online procurement partners as Deecorp, a local Softbank-related firm, Ariba has found a rapidly increasing market among Japanese firms trying to reduce costs. He related the case of one major firm, Ishikawajima-Harajima Heavy Industries (IHI), where the senior management instructed the procurement office to cut all purchasing costs by 20 percent within three years. Using reverse auctions, they expect to not only achieve the target, but to do so ahead of schedule.

The bottom line

The consensus of companies we surveyed is that auction-based procurement is really only effective for job lots and services selling for more than JPY20,000 to JPY50,000. As our GE source states: "Even the smallest jobs take time to set up, in our case about 30 minutes, and thus for us the practical lower limit for auctions was around JPY50,000."

According to Blaise Anthony, the average savings for the Chanel project were in the order of 20 to 40 percent. However, "it varies depending on the product and/or service you're dealing with. For instance, on furniture and some higher ticket items, we were able to save up to 44 percent, and in several cases, I have been able to extract savings of up to 75 percent from the list price."

Our GE source agreed with this, using the example of a surprising 50 percent savings on floppy disks bought by auction. Clearly, the impact of auction-based procurement on the bottom line can be significant, particularly for the average foreign multinational. @

|