Business is Booming -- At Least in Kabukicho

Back to Contents of Issue: September 2003

|

|

|

|

by Stephen Mansfield |

|

|

A district of non-descript shops and modest wood and mortar residencies, Kabukicho in the immediate post-war years, as Peter Popham observed in his book Tokyo: The City at the End of the World, "had no tradition; practically the only structure still left standing after the air raids was the elevated railway. All it had was a hungry energy." Shrewdly channeled, that was more than enough to turn the area into a commercial phenomenon. Kabukicho took a few more years, however, to find its feet. Even in 1948 the worst of the taprooms and grog shops of early Kabukicho, shanty taverns erected in two to three days by itinerant carpenters, were still serving the noxious kasutori to their customers, a liquor which was known to cause blindness if drunk to excess.

Like any vibrant market, Kabukicho's sex Hoping to lift the spirits of the post-war Japanese, plans were floated at this time to rebuild the destroyed Kabuki Theater, to burnish the area's image with the presence of one of the traditional performing arts. In the end, the playhouse stayed in its original Ginza location, and the gangs operating near Shinjuku station's exits and in its huge black market took over the area, changing its aspirations but keeping the name. The US occupation authorities may have had a small hand in this. With their inherent suspicion of traditional culture, feudalism and the samurai ethic, kabuki was banned for a period at the onset of the occupation. Public morals were better served, apparently, by a red-light district happy to cater to the restless GIs, who were among those attending Japan's first strip show, "The Birth of Venus," in Kabukicho.

Chinese and Taiwanese interests in the area, often presented in an ominous light as if they were recent manifestations of those countries' powerful crime syndicates and cartels, actually date from the immediate post-war era, when overseas Chinese funded much of Kabukicho's development as a legitimate entertainment district. Their Chikyu Kaikan (Golden Hall) still exists on the south side of Koma Square. The hall contained a cinema, the Chikyuza, known for showcasing Russian and European art films. Film houses and coffee shops drew students and intellectuals to the area.

As Donald Ritchie notes in The Image Factory: "Enterprise, imagination, application, and sheer single-mindedness have, in Japan, turned an instinct into an industry, have carved an empire from an urge." According to CNN's Money magazine, the empire of the shadow economy, of which the flesh trade accounts for a large percentage alongside other steady earners like extortion and narcotics trafficking, was worth some JPY19.3 trillion at the end of fiscal 2001. This is double the size of the entire Irish economy.

People in recession-riddled While other sectors of the economy have shrunk during the current recession, the sex trade has adapted and flourished. Three years of deflation as measured by government statistics has meant reduced company profits, an erosion of salaries and an increased loan burden for the country's embattled banks. But in the flesh trade, deflation means that carnal desires are cheaper to satisfy, a fact that sparks growth. Cheaper services for workers on increasingly pinched wages have caused prices to plunge but overall revenues to surge. Part of this may be attributable to despair. Where people in other recession-riddled countries like Russia and Argentina are switching to hard liquor to console themselves, the Japanese are turning to sex.

The boom-and-bust pattern evident in other sectors of the economy is not necessarily detrimental to Kabukicho, where a fad, having run its course, is simply replaced with a new one. Baby salons are an interesting case in point. Nurseries where businessmen could exchange their workaday suits for diapers and bibs and receive the ministrations and occasional scolding from firm but kind "mommy" figures, baby salons did very well for a while, with customers rarely complaining when their wallets were suckled. The late author Shusaku Endo set several scenes in his 1986 novel Scandal in Kabukicho. "Our clients dress up like babies," the main character is told: "They play with rattles and baby toys. A lot of men wish they could be babies again." Many of these establishments are now running successful SM venues.

Often thought to be the exclusive preserve of salarymen and middle-aged males, the area today also attracts the young of both sexes, for whom it is merely an extension of any other large entertainment zone. "Plunging into the bowels of Kabukicho," the main character in writer Shimada Masahiko's experimental novel Dream Messenger is struck by the appearance of the young people there. "How superficial and timid they seemed. Born in Disneyland, raised in Harajuku, and nurtured on McDonald's -- they were hanging out in this playground for the pubescent." Another writer, Natsuo Kirino, captures the mood of the street, the not unpleasant sense-barrage that is Kabukicho, in her novel Out. A "wall of noise" prevails, with "speakers announcing the next show at a movie theatre, men hawking cheap goods on the corner, a popular tune blaring from a karaoke studio. A man handing out fliers, another advertising some kind of girlie show, and a gaggle of sluttish high school girls."

Although the scale and scope of its operations may have changed dramatically since the gray, commodity-short days of post-war Japan, Kabukicho is still engaged in doing what it has always done best: helping to put a little blood back into the faces of the city, and some cash into its own pockets. @

|

|

Note: The function "email this page" is currently not supported for this page.

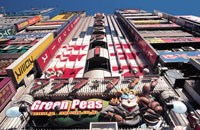

WARM TYPHOON SQUALLS LASH the streets, forcing couples to dash into love hotels for shelter. Neon signs cast great pools of light, molten chrome and sheets of magnesium across the taxi roofs of Yasukuni-dori, turning pedestrians into a phantasmagorical tableau vivant. A chalk line, inscribed by police on the sidewalk, dissolves in rain puddles, a faint sketch in the shape of a body on the asphalt. Scenes from a noir novel by Leonard Elmore or Peter Tasker? No, just an ordinary night in Kabukicho, Tokyo's premier sakariba, or pleasure quarter.

WARM TYPHOON SQUALLS LASH the streets, forcing couples to dash into love hotels for shelter. Neon signs cast great pools of light, molten chrome and sheets of magnesium across the taxi roofs of Yasukuni-dori, turning pedestrians into a phantasmagorical tableau vivant. A chalk line, inscribed by police on the sidewalk, dissolves in rain puddles, a faint sketch in the shape of a body on the asphalt. Scenes from a noir novel by Leonard Elmore or Peter Tasker? No, just an ordinary night in Kabukicho, Tokyo's premier sakariba, or pleasure quarter.

Any idea of creating Tokyo's Broadway faded as Shinjuku entered a new age with the relocation of the metropolitan trolley system terminus in 1949. Shortly afterwards, the Seibu railway extended one of its lines to the western edge of Kabukicho. In the same way that the police had given their tacit consent to the activities of Shinjuku's post-war black market, known as the "Dragon Palace Market," the entertainment locus that sprung up near this new transportation center met little serious opposition, an attitude that has held fast over the years. Unless a stabbing, handgun incident, or case of arson should occur, as they do from time to time, official Japan watches from the shadows but rarely intrudes.

Any idea of creating Tokyo's Broadway faded as Shinjuku entered a new age with the relocation of the metropolitan trolley system terminus in 1949. Shortly afterwards, the Seibu railway extended one of its lines to the western edge of Kabukicho. In the same way that the police had given their tacit consent to the activities of Shinjuku's post-war black market, known as the "Dragon Palace Market," the entertainment locus that sprung up near this new transportation center met little serious opposition, an attitude that has held fast over the years. Unless a stabbing, handgun incident, or case of arson should occur, as they do from time to time, official Japan watches from the shadows but rarely intrudes.

The beatniks of the 50s were displaced by hippies and practitioners of experimental theater in the 60s. East Shinjuku's preferred choice among the literary and arty types was reflected in the names of its watering holes -- the Bar Ibsen and Club Genet among them. These were replaced in the late 60s with establishments like What's New Pussycat and the Swinging Pink. Art and radical politics receded in the following decades as pimps, extortionists and hoodlums took over most of the remaining premises in Kabukicho 1-chome. With the exception of theaters like the Koma Gekijo, which puts on musicals and samurai dramas, the aspirations of today's Kabukicho are unabashedly low-brow.

The beatniks of the 50s were displaced by hippies and practitioners of experimental theater in the 60s. East Shinjuku's preferred choice among the literary and arty types was reflected in the names of its watering holes -- the Bar Ibsen and Club Genet among them. These were replaced in the late 60s with establishments like What's New Pussycat and the Swinging Pink. Art and radical politics receded in the following decades as pimps, extortionists and hoodlums took over most of the remaining premises in Kabukicho 1-chome. With the exception of theaters like the Koma Gekijo, which puts on musicals and samurai dramas, the aspirations of today's Kabukicho are unabashedly low-brow.

In this socio-economic climate where aphrodisiacs have become painkillers, good business models prevail. The area's multi-story porn shops, for example, are designed like mini-department stores. Pink salons, telephone clubs, and nozoki-beya peep shows are located in the basement, from which customers are channeled into elevators or up staircases whose photo panels advertise services to be had by ascending to higher floors, where video boxes, fashion clubs and sex-aid shops are located.

In this socio-economic climate where aphrodisiacs have become painkillers, good business models prevail. The area's multi-story porn shops, for example, are designed like mini-department stores. Pink salons, telephone clubs, and nozoki-beya peep shows are located in the basement, from which customers are channeled into elevators or up staircases whose photo panels advertise services to be had by ascending to higher floors, where video boxes, fashion clubs and sex-aid shops are located.

No other country in the world offers the sheer variety of sexual services found in Japan, where novelty is paramount. Since the 50s, when its coffee house hostesses, many of them amateurs, began dispensing extra services on the side, Kabukicho has been the most innovative of them all. The late 70s saw the advent of the no-pan kissa, establishments where waitresses shimmied between tables above mirrored floors, a clever, commercially successful concept yoking together coffee and fetishism. The late 90s saw the advent of "image clubs," where socially unacceptable practices like subway groping, sex between teachers and students, patient-nurse improprieties, the consequence-free violation of a female prison warden and other deviations could be indulged with impunity. Today's innovations include girls tearing off their panties and selling them on the spot.

No other country in the world offers the sheer variety of sexual services found in Japan, where novelty is paramount. Since the 50s, when its coffee house hostesses, many of them amateurs, began dispensing extra services on the side, Kabukicho has been the most innovative of them all. The late 70s saw the advent of the no-pan kissa, establishments where waitresses shimmied between tables above mirrored floors, a clever, commercially successful concept yoking together coffee and fetishism. The late 90s saw the advent of "image clubs," where socially unacceptable practices like subway groping, sex between teachers and students, patient-nurse improprieties, the consequence-free violation of a female prison warden and other deviations could be indulged with impunity. Today's innovations include girls tearing off their panties and selling them on the spot.

Like any vibrant market, Kabukicho's sex Kasbah combines earnest commodity and enterprise with leisure and entertainment to achieve a gratifying mix. While Koma Square has its cinemas and theaters, the rest of the area is rife with restaurants, bars, discotheques and game centers. Where there are quiet stairwells or abandoned alleys, fortune-tellers offer tarot-card readings. Inebriation is another form of indulgence common to Kabukicho, the hard liquor and ear-splitting bonhomie that are prerequisites of the male, after-office groups that roam the quarter, quickly turning their complexions into a hue not unlike iron oxide.

Like any vibrant market, Kabukicho's sex Kasbah combines earnest commodity and enterprise with leisure and entertainment to achieve a gratifying mix. While Koma Square has its cinemas and theaters, the rest of the area is rife with restaurants, bars, discotheques and game centers. Where there are quiet stairwells or abandoned alleys, fortune-tellers offer tarot-card readings. Inebriation is another form of indulgence common to Kabukicho, the hard liquor and ear-splitting bonhomie that are prerequisites of the male, after-office groups that roam the quarter, quickly turning their complexions into a hue not unlike iron oxide.