The Art of Killing Time Online

Back to Contents of Issue: February 2003

|

|

|

|

by Micheal Thuresson |

|

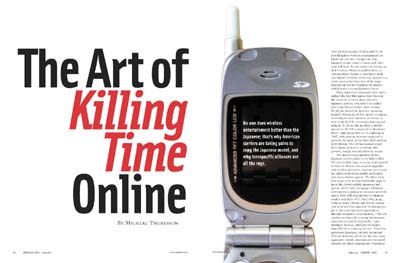

THE REMARKABLE POPULARITY OF downloadable wireless entertainment in Japan has not only changed the way Japanese people wait for trains and otherwise kill time, but its active inertia has carried overseas. Western markets have, in varying forms, begun to attempt to replicate Japan's wireless revolution. Japan's runaway success has been one of the main inspirations for the fledgling US market, which seeks a strong Japanese flavor. Many American companies have internalized the fact that games have become the driver of wireless data riches for Japanese carriers. DoCoMo's 14 million plus i-appli Java handset users average 3,500 yen per month in data fees, spending roughly 60 percent of this money on games, according to most industry estimates. A new study by IDC, a research firm specializing in IT, shows the number of mobile gamers in the US is expected to skyrocket from 7 million in 2002 to 71.2 million in 2007, with gaming revenues expected to grow in the same period from $130 million to $4 billion. The US has learned much from Japan on how to stimulate this growth, though several problems remain. The data revenue numbers of the Japanese carriers jump out at debt-ridden US carriers that have in recent years poured billions of dollars into network upgrades and wireless spectrum, but have yet to realize multimedia functionality and higher data transmission speeds. The short-term bets seem to be on low-bandwidth applications like downloadable ringtones and games, which take advantage of handset developments instead of increased network speed. This will ring familiar to Japanese market watchers. NTT DoCoMo, along with its rivals J-Phone and KDDI, created and perfected this approach of enticing people to use entertainment applications through attractive color handsets. "The US carriers are basically copying the Japanese successes as closely as possible," says Matthew Bellows, publisher of Boston-based Wireless Gaming Review. "Our first generation handsets, on both Sprint and Verizon Wireless, which are the two most aggressive mobile entertainment-oriented carriers, are direct adaptations of Japanese models. The clamshell design, the big color screen, even the brushed metal casing -- all are derived from successful Japanese designs." To draw attention to its ringtones and game offerings, Verizon Wireless, the largest US operator with over 30 million subscribers, spent the past fall blitzing the country with advertising for its "Get It Now" content service on feature-rich phones. Color screens, long a staple of Japan, have only emerged on a mass scale this year in the US, with Japanese manufacturers Sharp, Kyocera and Sanyo supplying a good portion of them. According to Bellows, the quality of the US phones and networks is impressive compared to the early days of i-mode. "The phones and networks are better in the US than they were in Japan in '99. DoCoMo's i-mode bandwidth goes at 9.6 kbps tops, while both Sprint and Verizon average roughly 30 kbps," he says. The fact that the wireless Java (J2ME) i-appli games exploded in popularity while running on DoCoMo's relatively slow second-generation (2G) network is a testament to the marketing, appeal and inexpensiveness of the handsets, and the cultivation of good, cheap content. The original i-appli handsets in Japan were almost all under $100, with many under $50, and there was also much greater selection than there is in the US. As in Japan, ringtones and games in the US are being flogged as an introduction to entertainment services. "The original i-appli handsets were the first DoCoMo models to use Yamaha's 16-voice chips, and the sound quality was a strong selling point," says Steve Meyers, a team manager at Layer-8 Technologies, a music media development company (and a subsidiary of LINC Media, Japan Inc Communication's parent company). By making the new, jazzier-sounding, game-enabled phones cheap, DoCoMo was able to get the phones in the hands of over 14 million users within two years, creating a mass market for content, and awakening game developers to the possibilities. The high number of i-appli phones in circulation was the impetus for the creation of some 60,000 unofficial, free sites in the i-mode universe. The US is at the beginning of this challenge: sparking developer innovation and feeding consumer interest. One question is, with a limited selection of pricey color handsets and erratic developer revenue sharing plans, can the US carriers inspire the kind of initial creative activity from developers that drove the interest in cool and useful content? As of September, Verizon's "Get It Now" service was offering only three color handsets -- one from Sharp and two from Motorola -- all of which sell in the wallet-popping $150-$300 range. Sprint offers a few slightly cheaper color models -- a $99 Sanyo model, a clamshell Samsung model for $149 and another Samsung model going for over $200. The good news is that many more color handsets are on the way, which should promote price reductions for the existing models. Lining developers' pockets There are other issues affecting the outlook for US game developers. DoCoMo created the market and took the first step by subsidizing new handsets and offering a generous split of the subscription revenue with official developers: 91 percent going to the developer, 9 percent to the carrier. US carriers, with a far smaller market at this point, are far less generous to developers and have done no handset subsidization to help the market grow. "US carriers' content business models are closely modeled on the DoCoMo revenue sharing arrangement, with the change here that carriers are keeping more on the order of 20 percent of download fees instead of DoCoMo's 9 percent," says Bellows. "They justify this by saying that DoCoMo got their wireless frequencies for free, while they had to pay for it." All of these factors have led to expensive initial wireless entertainment content offerings. For example, it costs $1.25 to download a single ringtone from official Verizon content provider Moviso, a subsidiary of Los Angeles entertainment conglomerate Vivendi/Universal. In comparison, i-mode users typically get two dozen or so ringtones for a 300 yen monthly subscription. Low development costs are a big reason for this. Major Japanese content provider Mobile Telecommunications says that ringtones are by far its most profitable content -- the company outsources ringtone development to China to cut costs. Trouble brewing US developers are faced with much higher development costs. Combined with the immaturity of the market, these costs have created much higher content prices. The total cost for making a single application using Verizon's Brew application platform (a licensed product of Qualcomm) is estimated to be between $2,900 and $4,650, depending on the complexity of the application. Bob Huntley, CEO of Dwango USA, the US subsidiary of the Japanese game development company, acknowledges the hurdles for potential Brew developers. At the CTIA wireless entertainment convention in Las Vegas in October, he questioned why developers must pay Qualcomm to approve and tweak their applications and contrasted this to the openness of Sun Microsystems' wireless Java protocol, J2ME. "Developers don't have to pay Sun to develop a J2ME application. Of course with Brew, you're getting more robust backend services, like billing," Huntley said. The problem is that those backend developer services are necessary because Verizon has not established them in its business model. Instead, San Diego-based Qualcomm, once a major handset vendor but now a global giant with its CDMA network technology, stepped in between developers and the carrier. While Brew incorporates many necessary mobile entertainment business functions, such as billing and distribution for applications, it passes costs on to the consumer, and Qualcomm's royalties dig into the revenue of US application developers. "Qualcomm takes 20 percent of the wholesale price, and Verizon marks up the price to the consumer from there. For ringtones, 50 percent of subscriber revenue eventually goes to Verizon," says Seamus McAteer, principle analyst at Zelos Group, an advisory services firm specializing in wireless technologies. Qualcomm's Brew is taking a different form in Japan, where it must compete with a very advanced wireless Java development industry. KDDI is the only carrier to use Brew in Japan, phasing it in beginning in March through pre-installed Brew applications. In December, the carrier was scheduled to release its Brew specifications to developers, with several consumer and enterprise applications signed on for the official launch of Brew in February 2003. Unlike its deal with Verizon, KDDI's Brew must compete alongside the very popular KDDI J2ME developer community. This has altered the way Brew is deployed. "KDDI is making sure no royalties will be taken from the shared content revenue between themselves and content providers," says an executive from the wireless media division of a Japanese trading company. "If KDDI didn't do this, then nobody would come to the Brew market because their sales point is that it's open-platform. That is why my guess is that KDDI is paying royalties in advance to Qualcomm."  Waiting for carriers to step up

Waiting for carriers to step upUS developers, especially those familiar with Japan, are waiting for the carriers to step forward and actively create the market. "Carriers need to step up and do more integration for the various handsets in the market," John Smedley, senior vice president and chief operating officer of Sony Entertainment, said at the CTIA Wireless Internet convention in Las Vegas. "They need to take the burden off developers because it is currently too time-consuming." Interestingly, the hurdles presented to the US development world mean that a good portion of US content, especially games, will be culled from the proven developer bases, both in Japan and South Korea. As a result of the lack of a strong carrier-led content ecosystem in the US, Nokia and Motorola have emerged as global content aggregators and clearing houses for gaming applications. Both companies have appeared as major allies for export-hungry developers in the advanced and increasingly competitive gaming markets in Japan and South Korea. This is crucial for smaller but innovative Japanese development companies that lack the resources to export to the US. "Right now, many Japanese content providers are unsure of how to do business in the US," says the trading company executive. Nokia's Web-based comprehensive developer resource, Forum Nokia, is part of the Finnish company's effort to foster third-party software development across the globe for its handset technologies. Two recent announcements have signaled that the company's energies are focused on sourcing game content from Asia. In September, the company announced a partnership with the Korean Game Development and Promotion Institute, a partnership that will involve exporting hundreds of Korean games to the European and US markets. "The agreement provides access to handsets and special access to channels of distribution," says Lee Wright, director of global developer marketing at Nokia's US headquarters in Dallas. "It is testament to the quality of the games that we see coming out of many of the developers in Korea. We're able to accelerate the development of these applications and ensure that Nokia's operator partners around the world are able to offer them to their customers." Meanwhile, Nokia Japan announced in November the formation of a game publishing unit that will acquire games for Nokia devices (the vast majority of which are sold outside Japan), mainly from Japanese, but also from Chinese, Korean, Taiwanese and other regional game publishers and developers.  The idea that Japanese content can succeed in Western countries runs counter to a popular opinion that Americans won't take to Hello Kitty downloads and content based on Japanese tastes. While cultural factors have to be accounted for, most wireless gaming experts believe great games are universal and should not be dismissed as cultural aberrations. "Sure, there are some cultural flukes, but I don't know that I'd include cool mobile games in that group," says Nokia's Wright. "A cool game is a cool game in almost any language or culture." US carriers, despite the inherent differences they have with Japanese carriers, are subscribing to this theory to some degree as well. Sprint signed on Japanese game developer Namco, which has a US subsidiary, to supply a wireless version of its video arcade classic, "Ms. Pac-Man," along with several popular titles that have succeeded in Japan. "If a Japanese developer has a big transnational brand, there's real carrier interest here now," says Bellows of Wireless Gaming Review. "Also, if a Japanese company has risk-tolerant money to invest in US expansion, US carriers will talk with them because of their success in Japan."

The idea that Japanese content can succeed in Western countries runs counter to a popular opinion that Americans won't take to Hello Kitty downloads and content based on Japanese tastes. While cultural factors have to be accounted for, most wireless gaming experts believe great games are universal and should not be dismissed as cultural aberrations. "Sure, there are some cultural flukes, but I don't know that I'd include cool mobile games in that group," says Nokia's Wright. "A cool game is a cool game in almost any language or culture." US carriers, despite the inherent differences they have with Japanese carriers, are subscribing to this theory to some degree as well. Sprint signed on Japanese game developer Namco, which has a US subsidiary, to supply a wireless version of its video arcade classic, "Ms. Pac-Man," along with several popular titles that have succeeded in Japan. "If a Japanese developer has a big transnational brand, there's real carrier interest here now," says Bellows of Wireless Gaming Review. "Also, if a Japanese company has risk-tolerant money to invest in US expansion, US carriers will talk with them because of their success in Japan."This is exactly what Motorola was thinking when it tapped into Japan's advanced game software talent base through Japanese development house eValley, a prominent maker of wireless Java games. Motorola obtained the rights to several Japanese games for its Java-enabled phones for Nextel, the fifth-largest carrier in the US. In a sign of progress for the US gaming market, eValley was led to this deal through its alliance with a third-party content publisher, New York-based Micro Java Network, which offers its services to developers at no cost. "Micro Java Network's mission is to leverage the creativity and expertise of developers on a global basis, as well as to provide technical assistance and coach developers on the process of working with US carriers," Tim Meyer, president of Micro Java Network, was quoted as saying in a company press release. The US has taken its wireless entertainment offerings to another level in the past six months. Introducing Americans to the idea of using the phone to entertain, kill time and otherwise express themselves has been the general advertising theme. In a recent national television commercial for a carrier's ringtone service, a cell phone, humanized with a man's head on the screen, begs someone to help ease his boredom from playing the same ringtone over and over again. Japan set the curve for incorporating this kind of fun into the cell phone. Now, the many transpacific alliances springing up means Japan will have a heavy hand in shaping the US market in months to come. @ |

|

Note: The function "email this page" is currently not supported for this page.